Let’s start off today’s essay with a little poll. How do you pronounce the word “three”? Is it closer to a “free”, or is it closer to a “tree”, or perhaps just a plain old “three”?

As we covered really long ago, the ‘th’ sound is actually a pretty rare sound across the world, but it somehow exists in English. But even within British English, this ‘th’ sound is not universal — some regions might realise it as an ‘f’, while others realise it as a ‘t’. And for some non-native speakers of English, ‘th’ might sound like an ‘s’. Today, I want to look at the phenomenon where ‘th’ is pronounced as an ‘f’. This makes ‘three’ and ‘free’ sound pretty much the same.

This phenomenon is called th-fronting, where the ‘th’ sound, or [θ], is pronounced like a [f], and its voiced counterpart is pronounced like a [v]. The reason it is called fronting is, the [f] and [v] sounds are articulated further forward in the mouth, i.e. the lower lip, compared to the alveolar ridge or teeth for the [θ] and [ð] sounds.

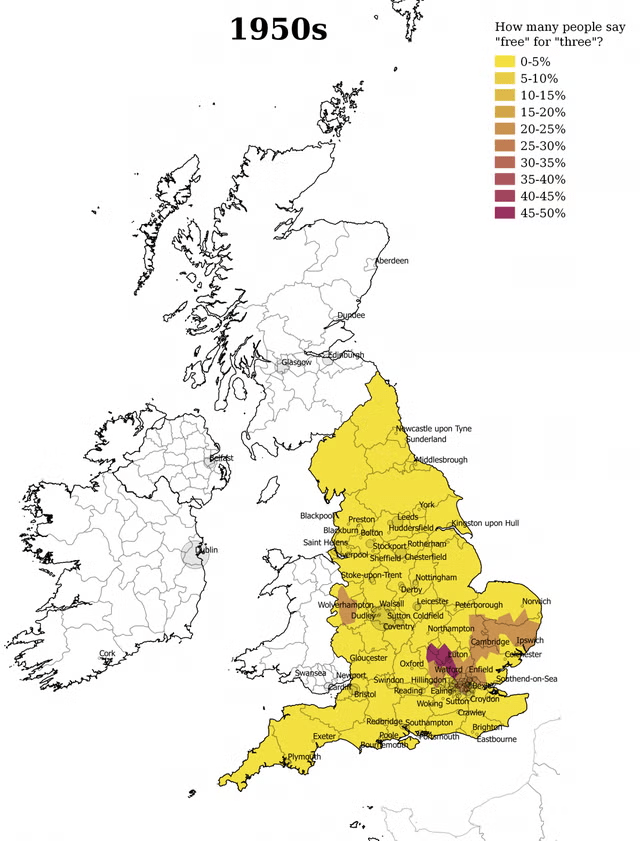

Th-fronting seems to be concentrated in London, the South-East, Hull, and Plymouth today, but it used to be more prevalent only in North London, some parts of Suffolk, Essex, Cambridgeshire, and Shropshire in the 1950s. But its history could have stretched a bit beyond this. 19th-century sources like Joseph Wright’s 1892 publication A grammar of the dialect of Windhill, in the West Riding of Yorkshire have reported some forms of th-variation in Yorkshire in the 1850s. Check out pages 90 to 93 in the publication for more details.

Percentage of people pronouncing ‘three’ as ‘free’ in the United Kingdom in 2016 (left), and in the 1950s (right) (Business Insider).

But this phenomenon started gaining interest in the mid- to late-20th century, when surveys of English dialects were conducted to get an idea of how English sounds varied throughout England, and later, the United Kingdom, giving maps such as the one above in the right. One of the most prominent dialects with th-fronting was Cockney English, with musicals like the 1960 Fings Ain’t Wot They Used T’Be showcasing it. One name pair this phenomenon reminds me of is Keith and Keefe, but to what extent th-fronting plays a role here is not quite clear to me, since they ultimately have Gaelic origins.

Th-fronting has been increasingly noticed in various dialects of English, with more people beginning to use it over time throughout the United Kingdom. Some have postulated that this could be the influence exerted by the dialects of London and South-East, which have permeated local dialects through linguistic or sociolinguistic processes. Younger speakers are also more likely to pronounce ‘th’ as ‘f’ in the United Kingdom, which has sparked some media attention in recent times. But it has been criticised as “improper” pronunciation, as with this Independent article below.

The contents of this article illustrate the process of homogenisation of accents and dialects in the United Kingdom, using examples of pronunciations of various words. They noted a convergence towards varieties of the South East and perhaps London, and away from local ones. But to say that th-fronting is an example of ‘improper’ pronunciation really rubs me the wrong way. Many phonetic mergers have been observed in the varieties of English which have developed from various sound changes, such as the pen-pin merger and the cot-caught merger seen in accents of America’s South and some parts of Canada respectively. Would these be considered ‘improper’ pronunciations? I think that this phenomenon illustrates the evolution of the English language as a whole, and how such phonetic mergers are being observed in real time. To say that such a deviation in pronunciation is ‘improper’ really shines a prescriptivist bias from the article.

A more recent documentation on the spread of th-fronting is in Scotland, when in the 1990s, an increasing number of young and working-class speakers pronounced ‘th’ as an ‘f’. While first noted in Glasgow in the late 1990s, this phenomenon has also made its way into Edinburgh as well, as noted in this publication in 2013. In these parts, particularly Glasgow, ‘th’ was traditionally more likely to be pronounced as a ‘h’, especially at the start of the word, or before ‘r’. This phenomenon is known as th-debuccalisation. Some factors have been proposed to influence this phonetic change, including the use of television programmes, which tend to focus more on English using Received Pronunciation or some accents from the South. It is an interesting process that is occurring in real time, which could change the landscape of English accents in dialects between rural and urban Scotland.

Th-fronting is not confined to just the United Kingdom itself either; it has been reported in African-American Vernacular English or AAVE, and has been associated with some interesting sociolinguistic phenomenon in Philadelphia. Reported by linguist and researcher Betsy Sneller in 2020, she proposed that hostile interactions along racial lines could bring along linguistic change, as white English speakers in South Philadelphia feature th-fronting transferred from AAVE.

Similarly, th-fronting has also been reported in Hong Kong English, although the ‘th’ sound may also be realised as an ‘s’ by some speakers as well. As [θ] and [ð] are not native sounds in Cantonese, it is likely that Cantonese could have played an influence in shaping the Hong Kong variety of English by substituting [θ] and [ð] with familiar sounds with acoustic similarities. Jette G. Hansen Edwards investigated the factors that could result in one pronunciation over the other in 2018, and found that English proficiency has an impact on the realisation of [θ], with the ‘f’ sound being more likely adopted by speakers of lower proficiencies, and the ‘s’ sound being acquired in higher proficiencies. Distinction between [θ] and [f] was also remarked to be more difficult by Hong Kong English speakers of lower proficiencies. Hansen Edwards concluded that such a variation in the ‘th’ sound is predominantly a linguistic phenomenon in Hong Kong English, which has to do with how this sound is acquired. But there could still be prescriptivist influences from British or American English, as there could still be a general perception of th-variations as ‘erroneous’.

As I read further into this topic, I found a wealth of publications dedicated to studying this very phenomenon. It is safe to say that there is academic interest in researching this very part of English speech and its varieties, which contributes to understanding how these sound changes could and would happen over time. Additionally, there is also academic interest in investigating the linguistic or sociolinguistic processes underlying these sound changes, forming an understanding of the evolution of English varieties that is happening as we literally speak. Could the th-fronting phenomenon spread further to other English varieties beyond the United Kingdom and form a three-free merger? Well, that remains to be studied.

Afterword

This essay was partly inspired by observing how some YouTubers speak. Smallishbeans is one example who demonstrates this phenomenon of th-fronting, and has been noticed by his community. While he has been aware of his articulation of ‘th’ as ‘f’, it led me to study more about the prevalence of this phenomenon and how it might have spread in English-speaking populations. It is quite an interesting phenomenon, and I would want to read more about how else ‘th’ could be pronounced, and the linguistic processes that could play a role in these pronunciations.

Further Reading

Hansen Edwards, J.G. (2019) ‘TH variation in Hong Kong English’, English Language and Linguistics, 23(2), pp. 439–468. doi:10.1017/S1360674318000035.

Schleef, E. and Ramsammy, M. (2013) ‘Labiodental fronting of /θ/ in London and Edinburgh: a cross-dialectal study’, English Language and Linguistics, 17(1), pp. 25–54. doi:10.1017/S1360674312000317.

Sneller, B. (2020) ‘Phonological rule spreading across hostile lines: (TH)-fronting in Philadelphia’, Language Variation and Change, 32(1), pp. 25–47. doi:10.1017/S0954394519000140.

Stuart-Smith, J., and Timmins, C. (2006). ‘Tell her to shut her moof: the role of the lexicon in TH-fronting in Glaswegian. In The Power of Words, Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789401203722_014.

Wright, J. (1892). A Grammar of the Dialect of Windhill, in the West Riding of Yorkshire, London, United Kingdom.