A while ago, we discussed the plausibility of a language to have fewer than two phonemic vowels, using the Moloko language as a case study. We ultimately learned that Moloko could have one or two phonemic vowels depending on how one analyses its sound system, and breaks down its surface vowel system.

However, when reading up further on this topic, I came across a presentation by Ekkehard Wolff that made a rather unusual assertion, that there is a language that can be analysed as not having any phonemic vowels. It built upon a publication by Newman in 1977, which argues that certain surface vowels in the Chadic language branch are not fully contrastive, using the vowel pairs /i/ and /u/, /i/ and /ə/, and /ə/ and /u/ as examples. This results in the Newman suggesting that the common ancestor of the Chadic languages, Proto-Chadic, could have had at most four phonemic vowels /i ə u a/, or as low as two /a ə/.

Reading on, I found this part where the Central Chadic languages may have examples where a language may have fewer than 2 phonemic vowels, and even none at all. Amongst the Central Chadic languages which may have one phonemic vowel, the Moloko language (introduced previously) and the Lamang language (mentioned as “in press” by Wolff) were mentioned as examples. And for the languages with no phonemic vowels, the Wandala language was mentioned.

And so today, let us take a look into the Wandala language, also known as the Mandara language (which also shares this name with an Austronesian language). Spoken by around 40000 native speakers in Nigeria and Cameroon, the Wandala language, like the Moloko language, belong to the Central Chadic grouping of the Chadic branch in the Afro-Asiatic language family. Within this language, there are two general varieties, called the Mura and the Malgwa varieties.

Like the Moloko language, Wandala has a rich consonant inventory, which includes the glide consonants /j/ and /w/, as well as labialised, palatalised, and glottalised consonants. However, this richness is consonants is contrasted with the relative paucity in vowels in the Wandala language.

From the surface, we see that the Wandala language has the vowels [a i u e o ə]. Frajzyngier’s 2012 publication also mentions the nasal vowel õ, and the language does not really distinguish between short and long vowels. Instead, long vowels are argued to be a result of speaker hesitation or other sociolinguistic or expressive processes. These, nonetheless, are transcribed in linguistics publications anyway, such as the /u/ in the word úunà (now).

The first propositions for Wandala’s vowel system suggested that the language has two phonemic vowels, [a] and [ə]. The latter, a high central vowel, is also transcribed as [ɪ], but the schwa is sometimes used to visually distinguish this vowel from [i], which can be rather ambiguous when tones are marked. This hypothesis by Mirt in the 1969 publication ‘Einige Bemerkungen zum Vokalsystem des Mandara‘, or ‘Some Remarks on the Vowel System of Mandara’, suggested that the other surface vowels are merely just allophones of these two vowels, and their occurrence is predictable based on the phonetic environments in which these vowels are located. [e] would be a variant of [a] between alveolar nasal consonants, and [ə] before a pause. This interpretation, however, was insufficient in accounting for the phonetic realisations of Mandala’s vowels, as there are no records of Mandala words or morphemes ending in either [ə] or [ɪ] in isolation. As such, the two-vowel model stands on somewhat shaky ground.

Several decades later, we get Wolff and Naumann’s proposition that inspired today’s topic. The zero-vowel hypothesis. This stemmed from the diachronic approach that Wolff purported, wherein the effects of developmental processes since Proto-Central Chadic can be observed in the synchronic reflexes of the Central Chadic languages spoken today. Before we move on, we should clarify that a language without phonemic vowels does not imply that a language is essentially just a bunch of consonant sounds. Instead, where consonant clusters are not permitted in a language, some epenthetic vowel can be inserted in a predictable manner. Consider the string of consonants [flt]. In a language with no phonemic vowels, vowels would only serve to break up impermissible consonant clusters. Thus, if [lt] is not a permitted consonant cluster, then the only way [flt] could be realised is as [flat], with [a] as an epenthetic vowel.

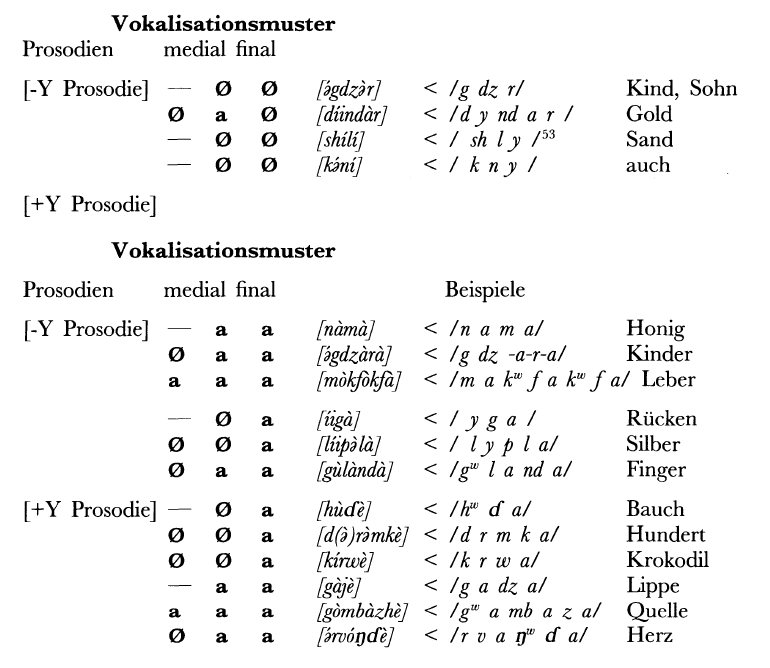

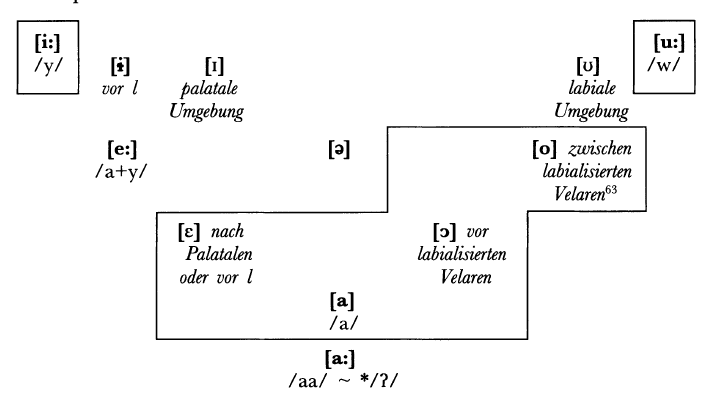

In the publication, Wolff and Naumann analysed the vowel system of Wandala by how the Y-prosody works. They found that the [e:] vowel is essentially a diphthong of /a + y/, something like the –ay sound in ‘day’. The short [ɛ] vowel is also predictable, as it occurs after palatal consonants or before /l/. Additionally, the [o] and [u] vowels are essentially surface vowels of some underlying vowel that is found between or before velar consonants. This allowed them to reduce the vowel inventory of the Wandala language.

Wolff and Naumann concluded with the following diagram. The enclosed vowels in boxes are considered to contribute some phonological meaning, while those that are unenclosed cannot be considered as phonemic vowels. It does seem that, considering the prosodic processes and other assimilation that takes place, the Wandala language might actually only have a single true phonemic vowel, [a], if it could be considered as one.

Arguably, [ə] here could be interpreted as an epenthetic vowel, and would not constitute a phonemic vowel. This leaves [a] as the only apparent phonemic vowel in Wandala, though as we will see in a future essay, some would be inclined to reduce it further, terming it as a mere feature of openness or something.

In fact, as Wolff suggested in his presentation on vocalogenesis in the Chadic languages, there are hypotheses that entailed that there might not have been a phonemic [a] sound at all. Instead, this would have been a glottal stop in Proto-Central Chadic, and the vowel system on the surface would have been simply a manifestation of vocoids with epenthesis. Vocoids are not generally considered to be phonological vowels, but phonetic vowels. As such, depending on the diachronic stuff used in the analysis, whether of not Wandala has or lacks phonemic vowels is up in the air. As it stands, it seems that on a deep level analysis, Wandala has one phonemic vowel from Wolff and Naumann’s 2004 publication.

However, Frajzyngier’s analysis arrived at a three-vowel system, a bit different from Mirt’s 1969 proposal, and Wolff’s 2004 argument. Here, he proposed the underlying [a], [i], and [u] vowels, contrasting with the [a] and [ə] proposed by Mirt in 1969. How [e] was reduced stemmed from the observation that the [e] vowel only occurs in two environments, often before a pause, or at the end of a clause. Sometimes, this vowel may be found in between certain consonants, and as in Wandala phonotactics, no word may end in an obstruent, this suggests an epenthetic property to it. Frajzyngier suggested that [e] is a product of front vowel lowering from [i], drawing comparative examples between Wandala and another Chadic language, Hdi. Where Hdi words would end in an [i], Wandala would end with an [e] sound. The [o] sound, on the other hand, is generally interpreted as a variant of [a], and occurs when then [a] sound occurs before the labial glide sound [w], except when [w] is followed by a vowel.

The relegation of the [e] and [o] vowels to secondary status is not quite surprising here. In fact, across the Chadic languages, these vowels tend to be found in loanwords, or derived from either diphthongs or other processes. But yet, we cannot truly give an answer on whether or not Wandala really lacks phonemic vowels. Ultimately, what it boils down to is how the vowel system is analysed, and how the [a] and [ə] vowels are treated.

Further Reading

Frajzyngier, Z. (2012) A grammar of Wandala, De Gruyter Mouton.

Mirt, H. (1969) ‘Einige Bemerkungen zum Vokalsystem des Mandara’, In Voigt, W. (ed.), XVII. Deutscher Orientalistentag vom 21. bis 27. Juli 1968, in Würzburg: Vorträge, Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner Verlag, pp. 1096-1103.

Newman, P. (1977) Chadic Classification and Reconstructions, Afroasiatic Linguistics, 5(1), pp 1 – 42.

Wolff, H. E. & Naumann, C. (2004) ‘Frühe lexikalische Quellen zum Wandala (Mandara) und das rätsel des Stammauslauts’, In Takács, Gábor (ed.), Egyptian and Semito-Hamitic (Afro-Asiatic) studies in memoriam W. Vycichl, Leiden: E.J.Brill, pp. 372-413.

Wolff, H. E. (2015) “‘Vocalogenesis’ in (Central) Chadic languages”, MPI.EVA Closing Conference on Diversity Linguistics: Retrospect and Prospect 1-3 May 2015, Leipzig.