In 2025, I started the year with a particular goal in mind. I wanted to commit fully, to the best of my ability, to learn an indigenous language, and reflect on this process towards the end of the year. Now that it is the December of 2025, it is finally time to share this experience.

It took me a while to research, read up, and decide on which indigenous language to start learning. Such factors included accessibility to language resources, familiarity with cultural norms and taboos, and the extent to which the language learning process would be a challenge (which I appreciate). While I really like learning more Austronesian languages spoken in the Central and South Pacific, my mind eventually settled on the Northern Sámi language, or Davvisámegiella. But first, an introduction to the Sámi languages.

The Sámi languages are traditionally spoken throughout the cultural region of Sápmi, an area encompassing parts of Sweden, Finland, and Norway. Davvisámegiella is perhaps the northernmost Sámi language spoken today (and hence the name), as well as the most widely spoken Sámi language as well. While Northern Sámi is related to Finnish, or at least, is classified under the same language family as Finnish, the Sámi languages are grouped as a separate branch from the Finnic languages like Finnish. Within this branch, Northern Sámi is most similar to the Lule Sámi and Pite Sámi languages, which are spoken in the Sápmi cultural region that overlaps with Sweden and Norway.

One of the most accessible resources I consulted during this learning journey was oahpa.no, a platform provided by UiT The Arctic University of Norway. These lessons are provided in Norwegian, and there are also various exercises, grammar and vocabulary pointers to help users and learners practice certain features of Davvisámegiella. There is also another application called indyLan, which is a platform featuring some of Europe’s languages, namely, Scots, Gaelic, Davvisámegiella, Cornish, Galician, and Basque. indyLan also includes a separate section featuring the culture and history of the respective language chosen, for learners to pick up, respect, and appreciate as part of the language learning process. I might do a review of these down the line, so we will see how my review writing goes. But anyway, these were my primary resources used to learn Davvisámegiella.

I think the main challenge was picking up the grammar bits here and there through oahpa.no, since I am not a native Norwegian speaker, nor do I consider myself confident in using Norwegian. In fact, when using the online Davvisámegiella dictionary, I would pretty often find myself translating between Finnish and Davvisámegiella, rather than between Norwegian and Davvisámegiella.

This ended up becoming routine, as I used two bridging languages to learn Davvisámegiella, Norwegian for grammar, and Finnish for vocabulary. After all, when I first started, I thought it would be great to be able to compare Finnish words with Davvisámegiella ones, since they are at least somewhat related languages, and so, there would be some words in Davvisámegiella that would appear familiar from my experiences in learning Finnish. However, I would be proven rather wrong. From words like beaivi (sun, FI: aurinko) to lieđđi (flower, FI: kukka), some everyday vocabulary generally appear different in Davvisámegiella compared to Finnish. There are loanwords, of course, though their etymologies can be a bit unusual. For example, while the word ‘computer’ translates to tietokone (literally ‘knowing machine’) in Finnish and datamaskin (‘data machine’, or ‘computer machine’) in Norwegian, how this word translates to Davvisámegiella would take the Finnish construction of the word, knowing machine, but uses the Davvisámegiella word for ‘knowing’, diehtit, and the Swedish word for ‘computer’ or ‘data’, dator, giving the word dihtor.

Being related to Finnish, there are definitely some similarities that I noticed in Davvisámegiella in terms of grammar. Consonant gradation is one of the most salient features in languages like Davvisámegiella and Finnish, as consonants may change when words are inflected for a certain grammatical function. It seemed that the consonant gradation system in Davvisámegiella is quite complex, and even after nearly a year into learning the language, I would find myself tripping up over this. Another salient common feature is the use of the negative verb, which is conjugated by mood, person, and number when a certain negative expression is made. One thing I found myself needing to get used to was the treatment of nouns and verbs as either even, odd, or contracted. I do not recall encountering this system of declension patterns when I was learning Finnish, so this was indeed something new.

As 2025 progressed, and so too did my lessons in Davvisámegiella, I was thinking of how best to demonstrate what I have learned. As I am a part-time streamer, I thought, in the second half of the year, I would introduce to my audience there a Davvisámegiella word that I have picked up at some point during the year. I think it is a decent practice for my pronunciation of Davvisámegiella words, and speaking Davvisámegiella instead of just reading and writing. But I do have a little plan for what I want to do for my writing bit.

In addition to the review of the Davvisámegiella resources I mentioned, I think I would try dedicating a post next year to be written entirely in Davvisámegiella, with a Finnish and/or English translation, just as a demonstration of how far I have progressed in the language in 2025. Overall, I have enjoyed my time learning Northern Sámi, and I am glad to have experienced the language and appreciate some of the cultural aspects of the far north. Looking to 2026, I think I will try this format of language learning again, and share my experiences at the end of the year.

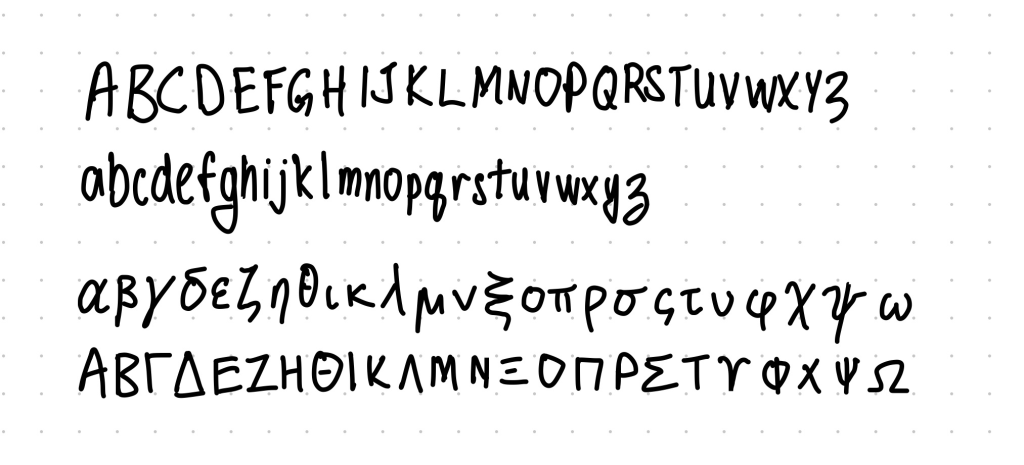

Lastly, as promised from the ninth-anniversary announcement, the long-delayed handwriting update is here:

Further resources

Oahpa Muinna – https://oahpamuinna.wordpress.com/