We have been quite unsuccessful in uncovering languages in Australia and Vanuatu that use a true system of case prefixes, with all of them using a mix of suffixes, particles, markers, and prefixes to mark a certain word for its case. In fact, one of the only languages near that region that has a system of case prefixes is the Enggano language in western Indonesia, which we have covered previously. We now cross the Pacific Ocean, arriving in the western coast of the Americas.. Starting first in Canada, we find another data point for a language reported to have case prefixes. Spoken in the province of British Columbia in Canada, this is the Shuswap language, or Secwepemctsín.

Translating to “the language of the spread out people”, Secwepemctsín belongs to the Salishan language family, making it most closely related to Lillooet and Thompson River Salish. This also makes it related to Nuxalk, the language known for its unusual consonant clusters that makes linguists question what makes a syllable. Like many indigenous languages of North America though, the Shuswap language is endangered, with around 200 native speakers according to the First Peoples’ Cultural Council, with around a thousand more speakers with some knowledge of the language. This translates to around 10-20% of the Secwepemc people who speak Secwepemctsín to some capacity, a rather concerning figure.

There are 6 vowels in the Shuswap language, with 5 full ones, /a e i o u/, and a reduced one /ə/. There is some suggestion of a sixth full vowel as well, transcribed as [ʌ], but its status is unclear. Such vowels may dictate the stress patterns in the Shuswap language, as the /i/ and /u/ vowels can only occur in stressed syllables, while /ə/ can only occur in unstressed syllables. Furthermore, the /e/, /i/, and /u/ vowels may also undergo a process called ‘darkening’ when around uvular consonants like /q/ and /χ/. This would alter how these vowels are pronounced, such as /e/, usually realised as [ɛ], being darkened to [a], /i/, usually [i ~ e], being darkened to [ɪ ~ ɛ], and /u/, usually [u ~ o], being darkened to [ɔ].

Like many Salishan languages, Shuswap distinguishes between plain and ejective consonants, with an ejective counterpart for every nasal, plosive, and approximant consonant in the language, except the glottal stop [ʔ], with no such distinction for the fricative consonants. There is also a rounding distinction for consonants with velar, uvular, and pharyngeal places of articulation, including this weirdly transcribed consonant [ʕʷˀ], which is the rounded ejective pharyngeal approximant. There is no voicing distinction in the Shuswap language, and neither is there a distinction between plain and aspirated consonants.

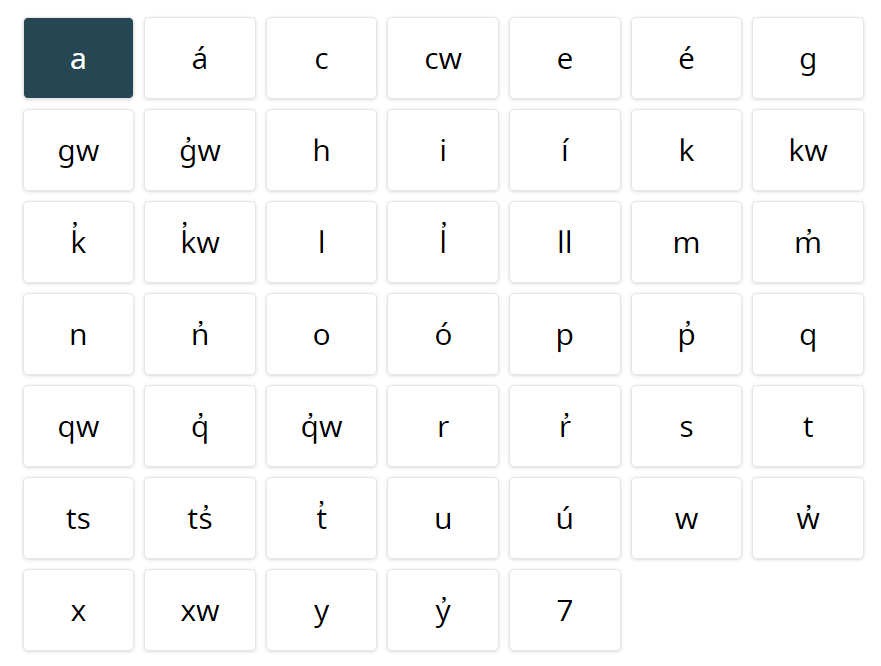

With the number of consonants that do not occur in the English language, transcribing Shuswap and giving it an orthography based on the 26 letters of the Latin alphabet is challenging. There are two different systems that have been used to transcribe the Shuswap language in addition to the International Phonetic Alphabet. For example, Aert H. Kuipers suggested using an orthography that included special letters like ɣ, ʕ, and ʔ, as well as the ‘ to mark ejective consonants, and ° to mark some rounded consonants, and the letter x̌ to represent the /χ/ sound. Another orthography may be found on FirstVoices, which uses apostrophes as a diacritic, and the 7 to represent the glottal stop.

The Shuswap language recognises two cases, the absolutive, and the relative. The absolutive is used to mark nouns as the subject of an intransitive verb, and the subject and object of a transitive verb. And for the relative case, it is pretty much used for basically everything else. Both of these cases are marked using prefixes, finally giving us an actual example of a language that uses a system of case prefixes. Additionally, there is also a locative prefix n-, but it does not seem to be interpreted as functioning as a separate grammatical case.

| Absolutive | ɣ- (proximal), l- (distal) | k- (irrealis) |

| Relative / Oblique | t-/tɬˀk- | tk-/tɬˀk- (irrealis) |

How these cases are used in the Shuswap language seems rather unintuitive however. And so, let us break this down into several situations.

Firstly, you have the intransitive. The subject is assigned the absolutive, with the distal one used for nouns that are outside the speaker’s view, or when they refer to the deceased or mythological entities. The distal is also used when talking about completed events. The irrealis prefix, on the other hand, is used to refer to a non-specific noun as well as with wh-questions like what and why. The locative, if present, may also be represented using the relative case here. Nevertheless, the most basic construction of an intransitive clause is the predicate consisting of a verb with tense and subject markers.

Next comes the transitive. Here, both the subject and the object take the absolutive case, with the verb taking suffixes to agree with the subject and object. This way, the object suffix precedes the subject suffix. There are also middle constructions, where in the active voice (I hit a tree), the patient of a verb is realised as the subject of a predicate (like the car drives smoothly). In this case, the subject is still marked using the absolutive case, while the patient of the verb uses the oblique case.

But what happens when you have a direct object and an indirect object involved, like in the sentence ‘I gave Bob a book’? The verb still agrees with the subject and object of the clause, but only two of the three arguments here may take the absolutive case to demonstrate their link to the verb agreement. The other object of the clause would take the relative or oblique case to distinguish between the two objects. As such, ‘John gave Mary a fish’ would translate to:

kəx-t-ø-ɛs ɣ-John ɣ-Mary tə-swɛwɬ

give-tr-3sO-3sS ABS-John ABS-Mary REL-fish

Lastly, there is the passive construction (I got hit by a car). In this case, the patient of the verb is marked using the absolutive, while the agent of the verb is marked using the relative. The verb would also be marked using the transitive suffix plus the object agreement marker, but the subject marker will agree with an unspecified noun, -m / –ɛm.

We should also note that word order is generally free, but the glosses I have read during my research for this essay, the word order seems to bias towards verb-initial word orders, and the subject and object could appear in any order. With an identical case marker for the subject and object in a basic transitive clause, it does create some ambiguity in determining who the subject and object are. It seems that this ambiguity is resolved using contextual information rather than syntactic ones.

Like many indigenous languages in predominantly English-speaking countries, the decline of the Shuswap language is heavily driven by the prohibition and restriction of the use of the language in places like schools, especially so in the brutal conditions of Canada’s residential schools. In schools like these, humiliation and punishment were the norm for students for not speaking English, and students would be discouraged one way or another from speaking their mother tongue. They were sometimes technically still allowed to speak it in schools, but the fear of punishment and the trauma therewith would have impacted attitudes to the language.

The generations affected by the residential school system of Canada would grow distanced from their mother tongue, a problem that persists to this day. Even after the conclusion of this system, Shuswap students would still enter an education system dominated by the use of the English language, with infrastructure and capacity to teach their mother tongue generally lacking. And so, the decline of indigenous languages like Shuswap continues, prompting an urgent need for revitalisation efforts to be implemented.

Fortunately today, there are some efforts targeted at connecting Shuswap children with their language. The first one is a programme known as a language nest, or cseyseten. These are schools dedicated to teach endangered languages to younger students, or at least in the earliest stages of education, through an approach based on full immersion into the language. Some schools might conduct this type of education entirely in Shuswap, and some schools would use a more familial-based approach to connect older speakers like grandmothers to children.

The Shuswap language has also been making strides into digitisation, with some language support being offered on the social media platform Facebook. On a more educational sphere, there are applications, notably on the Apple App Store, which are dedicated to teaching the Shuswap language, and hosting more cultural information such as folklore, stories, and pronunciation guides. All of these aim to contribute to Secwepemctsín‘s revitalisation initiatives in Secwépemc communities. With growing awareness of such ongoing movements to revitalise Secwepemctsín, we could be optimistic about the language’s survival in the future.

Further Reading

Introduction to the Shuswap language (Shuswap Band)

Gardiner, D. G. (1985) ‘Structural asymmetries and preverbal positions in Shuswap’, PhD thesis, Simon Fraser University.

Kuipers, A. H. (1974) ‘The Shuswap language’, The Hague, Mouton.