Previously, we have looked at the various types of airstream mechanisms we use to make sounds. Most of our languages only use a couple of these in the words we speak, while there are perhaps one or two that manage to use as many as 4 or 5. Today, we will look a particular type of process of speech production that involves a rather specific speech organ — the glottis, and the larynx (voice box).

As the name suggests, the larynx is where sounds are produced. Manipulating it would change the quality of a certain sound, that would contribute to phonation. This primarily involves control of the vocal folds, which can be made to vibrate, or abduct or adduct (widen and narrow respectively) to affect the airflow through the glottis. This may be mediated by muscles and other parts in the larynx, such as the arytenoid muscles. By some phoneticians, it is this process of sound production made by the vocal folds that defines what phonation essentially is. A wider definition of phonation however, would involve parts of the larynx beyond just the vocal folds which can affect the airstream generated.

There are generally three broad types of phonation that can depend on the state of the glottis, and the other parts of the larynx involved in manipulating airflow. These include voicing, sounds depending on how open the glottis is, and supra-glottal phonation, that is, phonation involving additional parts of the larynx. These not only allows us to distinguish between ‘g’ and ‘k’, but also our ‘k’ from ‘kʰ’ and beyond.

Major contemporary research in phonation and speech production have been led by the phoneticians and linguists Peter Ladefoged and Ian Maddieson, while more research on the physiological aspects of phonation, such as those directly looking at the larynx through laryngoscopy, are also done by linguists such as Jerold A. Edmondson. Some of their publications and works will be linked in the Further Reading section below. One method in particular also involves the characterisation of such phonation types through spectrogram and waveform analysis, and identifying some features of these types that could be distinguished by the speakers of the languages that use them.

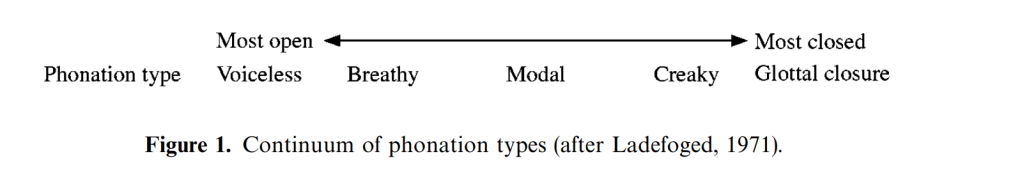

Ladefoged has also proposed a model of phonation types, which involves a spectrum of how open or how closed the glottis is, which ranges from voiceless phonation (you know, ‘k’, ‘t’, ‘p’) to the glottal stop (see also the introduction to airstream mechanisms). So, using this model, we can start to explore the different phonation types, starting with the phonation type using the most open glottis position.

Voicing

The ‘base’ or the ‘reference’ kind of voicing we would compare the various phonation types against is sometimes referred to as the modal voice. This involves the vibration of the vocal folds, which can actually be felt when you feel your voice box as you speak. It is most pronounced when you produce vowels, but consonants also have modal voicing. These consonants may also be referred to as voiced consonants when they exhibit a distinction from other phonation types, most notably, their voiceless counterparts. In most of the world’s languages, this modal voice may be contrasted against the other phonation types, which we will see below.

Voiceless phonation

One of the most common ways languages may distinguish between phonation types is by distinguishing the modal voice with the voiceless phonation. Briefly put, this is where a sound is produced that lacks the vocal cord vibration you would see in the modal voice. Physiologically speaking, this requires two states to be achieved — completely relaxed vocal cords, and a relatively open glottis (i.e. arytenoid cartilages being apart). Such a voicing distinction is observed in consonants, where you get your /k/ from the modal /g/, /p/ from /b/, and /t/ from /d/.

However, apart from these stop consonants that are particularly known for their likelihood of being distinguished by voicing in many languages, some languages may also have voiceless nasal consonants. Voiceless /n/ and /m/ may occur in several languages across Southeast Asia, for example, with notable examples including Burmese and Hmong. Interestingly, the Icelandic language also has such a system of distinguishing between voiced and voiceless nasal consonants. Such consonants may be transcribed using a ring diacritic attached below the sound, like [n̥].

Now that we have talked about voiceless consonants, how about voiceless vowels? According to Gordon and Ladefoged (2001), there does not seem to be a language that distinguishes vowels by voice phonemically, but the use of vowel devoicing has been observed in languages like Japanese, English, and even German. Japanese provides us with the prime example of vowel devoicing, where the mouth shape still reflects the vowel quality, but you do not necessarily hear it at all. Examples include the formal copula and verb ending -です (-desu) and -ます (-masu) respectively, which can be heard as -des and -mas. Most vowel devoicing largely pertains to the う (u) vowel here.

Breathy voice

Now what happens when you try to make the sounds as you would in the modal voice, but slightly constrict your glottis by a bit? This would produce a sound that some might remark as sounding like there is ‘some voice mixed with breath’. Perhaps this may also sound like a person talking while sighing. This is what some might refer to as the breathy voice, although some might also call it the murmured voice. This breathy voice is most notable during the first part of the vowel, and such phonation can even be absent, as the glottis could be too wide to vibrate the vocal folds.

My first memory of encountering such a sound is from the Gujarati language, which can occur in both its consonant and vowel sounds. I found two different ways of denoting this breathy voice distinction form the modal voice though, one using the character /ɦ/ like in [bʱ], while the other uses this diacritic resembling a diaresis on the bottom of the letter like [ə̤]. Gujarati also has aspirated voiced consonants like [bʰ], which could make distinguish between this and the breathy counterpart somewhat challenging as a learner of languages like this. For example, while બાર [baɾ] means “twelve” in Gujarati, બહાર [ba̤ɾ] means “outside”, while ભાર [bʱaɾ] means “burden”. Other languages that use the breathy voice include some Bantu languages, some Khoe and Kx’a languages, and some languages in India and Nepal such as Newari.

Creaky voice

This time, try making the sounds as you would using the modal voice, but tighten your glottis by a fair bit. Not all the way though, but more rather, leaving some openness such that voicing may still occur. Note the quality of the sounds that are made. They sound like a series of taps reflecting a certain sound, do they not? This is what a creaky voice essentially is. Sometimes, you would also encounter the term vocal fry.

Like the breathy voice, the creaky voice may occur in both consonants and vowels. Some languages also have a three-way distinction between the modal voice, breathy voice, and creaky voice phonations, with some examples including the Jalapa Mazatec language spoken in Oaxaca, Mexico, and some languages in Northwestern America such as Kwakw’ala and Montana Salish. The creaky voice is transcribed using the tilde diacritic ~, but like the other phonation types, it is attached below the corresponding letter affected by the creaky voice, as in [d̰].

While these languages distinguish between creaky and modal voice phonations phonemically, in languages such as English, the creaky voice, more accurately referred to as the vocal fry register, reflects a more sociolinguistic nuance. This is most pronounced in female American English speakers, although male speakers do use it to a lesser extent as well. While a 2010 study suggested that the vocal fry register indicated hesitation and informality in speaker, another study in 2011 suggested that its use by female speakers was to sound deeper, and convey a sense of authority.

In waveforms, both breathy and creaky phonations have lower intensities a lower fundamental frequency (the lowest frequency of a periodic waveform) when compared against their modal voice counterparts. The creaky voice here is most notable in the middle or end of a vowel. Nonetheless, even for such phonation types, these sounds all start off fairly modal, before the respective non-modal phonation types start to kick in.

Glottal stop

Finally, we have the state where the glottis is fully closed. This disrupts the airflow from the lungs, forming a stop in the glottis. A glottal stop. We have explored this type of sound in the introduction to airstream mechanisms, where such a sound can be combined with articulations to produce ejective consonants.

Supra-glottal phonation

Now that we have covered the phonation types involving the glottis at different states of openness, it is time to talk about the phonation types that would involve other parts of the voice box. These types are collectively referred to as “supra-glottal phonation”, although they can involve speech organs such as the false vocal folds and aryepiglottic cords. You may refer to Laryngopedia for laryngoscopy images for such phonations. These speech organs would be involved in the production of a couple of interesting phonation types, particularly seen in the Nilotic languages. These are the faucalised and harsh phonation types.

Faucalised phonation is also referred to as the hollow / yawny voice, which does sound similar to the breathy voice, but it sounds like speech mixed with yawning instead of sighing. Here, the larynx is lowered, but the pharyngeal cavity is expanded, and typically involves the part of the mouth/pharynx known as the isthmus of fauces (hence faucalised). This is the space between the soft palate and the base of the tongue. Unlike the other phonation types involving the glottis, this particular type of phonation does not have a commonly agreed upon diacritic that is recognised by the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA).

The harsh voice, on the other hand, involves the constriction of the laryngeal cavity, but involving the false vocal folds to do so. It does not sound like the creaky voice, however, and like the faucalised counterpart, there is no dedicated diacritic or character that is recognised by the IPA. This harsh voice may be trilled, involving the constriction of the pharynx and raising of the larynx, to produce a class of vowels known as the strident vowels. These are particularly observed in the Khoe-Kwadi, Kx’a, and the Tuu languages, conveniently grouped as the ‘Khoisan languages’. The main way I see these being transcribed is with the tilde attached below the vowel letter, as in [ḭ ḛ a̰ o̰ ṵ], resembling, and perhaps creating some ambiguity with the creaky voice.

I think that the most interesting case where these phonation types are used is in the Nilotic languages, as these phonation types can distinguish between movement toward, and movement away from the speaker. This is on top of the various phonemic distinctions made between these phonation types

Like we mentioned in airstream mechanisms, phonation does not occur on its own; to produce the sounds we use in language, airstream mechanisms, phonation, and articulation have to occur together. And so, to wrap up how we talk, we will look into the final phonological process underlying human speech production, that is, articulation.

Further reading

Borkowska, B. & Pawłowski, B. (2011) ‘Female voice frequency in the context of dominance and attractiveness perception’, Animal Behaviour, 82 (1), pp. 55–59. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2011.03.024.

Chhetri, D. K., & Neubauer, J. (2015) ‘Differential roles for the thyroarytenoid and lateral cricoarytenoid muscles in phonation’, The Laryngoscope, 125(12), pp. 2772–2777. doi:10.1002/lary.25480.

Edmondson, J. A. & Esling, J. H. (2006) ‘The valves of the throat and their functioning in tone, vocal register and stress: laryngoscopic case studies’, Phonology, 23(2), pp. 157–191. doi:10.1017/S095267570600087X

Esposito, C. M. & Khan, S. u. D. (2020) ‘The cross-linguistic patterns of phonation types’, L:ang Linguist Compass., 14, pp. e12392. doi:10.1111/lnc3.12392.

Floyd, W. F., Negus, V. E., & Neil, E. (1957). ‘Observations on the Mechanism of Phonation’, Acta Oto-Laryngologica, 48(1-2), pp. 16–25. doi:10.3109/00016485709123824.

Gordon, M. & Ladefoged, P. (2001) ‘Phonation types: a cross-linguistic overview’, Journal of Phonetics, 29, pp. 383-406. doi:10.006/jpho.2001.0147.

Ladefoged, P. & Maddieson, I. (1996). The sounds of the world’s languages. Cambridge, MA, Blackwells.

Rodgers, J. E. J. (1996) Vowel devoicing/deletion in English and German, Human Capital Mobility Phrase Level Phonology, pp. 177-195.

Tucker, A. N. & Bryan, M. A. (2018) [1966]. ‘Linguistic Analyses: The Non-Bantu Languages of North-Eastern Africa’, Linguistic Surveys of Africa, Vol. 18 (1st ed.), London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315104645.

Yuasa, I. P. (2010) ‘Creaky Voice: A New Feminine Voice Quality for Young Urban-Oriented Upwardly Mobile American Women?’, American Speech, 85(3), pp. 315–337. doi:10.1215/00031283-2010-018.