In 1511, the Portuguese Empire invaded and seized control of the city of Malacca, an important trading hub in the region. The colonisers intermarried with the indigenous women, and their languages intertwined, birthing a creole in the process. But Portuguese control of Malacca did not last. The Dutch took over Malacca in 1642, and later, the British came in and colonised the the Malay Peninsula, bringing it, Malacca included, and other Straits Settlements like Singapore, under “British Malaya”.

Despite losing contact with the Portuguese, this particular people group retained their language, only to experience its decline under the British, when their people moved away from their community for better opportunities. Some from Malacca also moved to Singapore, but like their Malaccan counterparts, they began to move towards learning, speaking, and using English or Malay. Over time, this has resulted in the loss of transmission of this creole language to the younger generations. This is the short oversimplified story of Papia Kristang.

Today, Papia Kristang is an endangered language, but it is seeing an ongoing revitalisation movement, with one of the most notable ones being Kodrah Kristang. Spoken by around a couple of thousand native speakers, Papia Kristang is a Portuguese-based creole, infused with linguistic influences from Bazaar Malay, Dutch, Tamil, Hokkien, and Cantonese. For instance, the word for ‘jellyfish’, ampeh, is derived from Malay ampai, the word for ‘toilet’, kakus, is derived from Dutch kakhuis, and the word for ‘spatula’, chengsi, is derived from Hokkien tsian-sî.

The phonology of Papia Kristang has a strong overlap with Bahasa Melayu, and there are some patterns of sound correspondences to take note when adapting Portuguese words into Papia Kristang. For instance, there are nasal vowels in Portuguese, such as não (no), but these vowels do not occur in Malay. These nasal vowels become normal vowels, but take the ‘ng’ sound at the end. As such, a Portuguese word like bom (good) would become bong in Papia Kristang.

Similarly, the /v/ sound does not occur in Malay, but it does in Portuguese. This /v/ sound becomes a /b/ in Papia Kristang, making Portuguese words like vós (you) and novo (new) become bos and nubu in Papia Kristang respectively. However, the /v/ sound can also occur in a restricted set of Kristang words, such as in novi (nine). Sometimes, this /v/ sound also disappears, such as when it occurs between two vowels. This is seen in words like Portuguese chuva (rain), which becomes chua in Papia Kristang. This ‘ch’ digraph is also pronounced differently between Portuguese and Papia Kristang — while Portuguese words beginning with ‘ch’ carry a [ʃ] sound, Papia Kristang words beginning with ‘ch’ carry a [tʃ] instead. There are several theories behind this, such as northern Portuguese dialects using [tʃ], the Portuguese spoken back then carrying [tʃ], or influences from Malay phonology.

While many words in Papia Kristang are derived from Portuguese roots, the grammar seems to bear strong similarities with Bazaar Malay and Bahasa Melayu. Verbs here do not inflect for tense, number, nor person, unlike in Portuguese, and some grammatical functions make use of particles and markers. For example, the tense markers include ja for the past, ta for the progressive (like ‘is doing’) or to mean ‘is becoming’ or ‘is newly, currently’, and logu or lo is used for the future. The word kaba may also be used to indicate an action which has been completed, taking on a similar function as habis in Malay. It may also occur as ja kaba, as one might occasionally observe in sudah habis in Malay. The combination ja ta may also be used for the past progressive (like ‘was doing’).

Some of these particles also have negative counterparts. For instance, there is the word ngka, which is used for negating the past and present. The word nadi is used for negating the future, nenang for the perfective, and nang for negating the imperative. All these markers precede the verb to be modified. There are also negative words for pronouns and things like nte (there is not), nada (nothing), nggeng (nobody).

Particles or markers may also be used to indicate the grammatical relationship of nouns in a clause or sentence. Perhaps one of the most common ones is the use of the particle ku or kung, which could be used to mark the accusative or the recipient of a certain action. This could also be used to express the comitative and instrumentative, as in eli bai ku yo na John sa kaza (He goes to John’s house with me). The benefactive, however, which is used to express the beneficiary of a certain action, is marked using padi, and more rarely, pada.

Possession is marked by the particle sa, as in yo sa kaza (my house). In a way, it resembles the possessive particle in Japanese no の, but its more direct influences perhaps came from how Bazaar Malay works. In Bahasa Melayu, ‘my house’ would be translated to rumahku, with the -ku suffix indicating that the pronoun ‘I’ is the possessor. But this is different in Bazaar Malay or Baba Malay, where we would encounter the phrasing aku punya rumah, which from Bahasa Melayu, would have translated to “I have a house”. This structure could be further traced back to how possession is formed in Hokkien as well. The particle sa in Papia Kristang derives from the Portuguese sua, which is the third person singular possessive pronoun used for a grammatically feminine possession, such as sua filha (her daughter).

The particle di, on the other hand, seems to be more used to indicate a part of something, such as the leaf of a banana tree. It is a derivation from Portuguese, which translates to “of” or “from”. This could give rise to compound nouns, such as when we compare phrases like fola di figu (leaf of the banana tree) and fola figu (banana leaf). Location is marked using na, but a goal of an action may also be marked using ku.

Personally, I have had some meaningful experiences learning Papia Kristang under Kodrah Kristang, through their regular classes in 2018. The learners I studied with are from diverse backgrounds, with some tracing their heritage to Malayo-Portuguese roots (with some having Portuguese surnames), and others picking the language up out of curiosity. There were no language nests for Papia Kristang to the best of my knowledge, and these classes proved the most accessible for those interested. While the lessons I took were free, these now incur a fee for facility costs as the lessons are currently conducted in a community center.

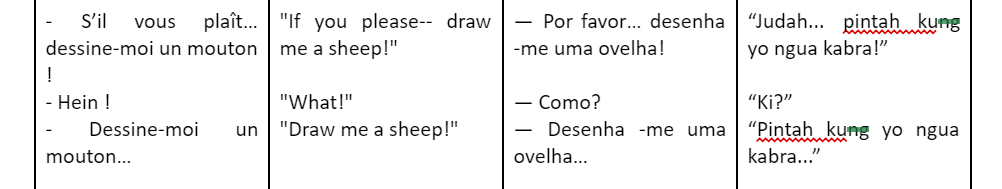

I have also tried doing a bit of translation exercises in Kristang, using the classic by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, The Little Prince, as a base for my translation practice. Below is a small excerpt of it, from left to right, in French, English, and Portuguese, with the rightmost one being the Papia Kristang translation I proposed.

However, it must be noted that there is no standardised orthography of Papia Kristang, although the one Kodrah Kristang seems to use aligns more towards an orthography based on Malay sounds. This system is the one I used when writing this essay. An advantage of this orthography is the lack of diacritics compared to a Kristang orthography that is based on Portuguese. The Malay-based orthography would also be relatively easier to pick up, making acquiring literacy in Papia Kristang easier.

Doing these translation exercises made me realise one problem in the revitalisation of the Kristang language. With centuries of contact with different languages, such as Malay and English, there would have been considerable influence on the Kristang language, such as in terms and words normally used in trade or in everyday Kristang life. But what about terms from science or technology? Going through the dictionaries I had access to, it seems that Kristang lacks words for many such terms, such as “digestion”. The print dictionaries I have also seem to be lacking in some of these terms as well.

This is when I encountered the Jardinggu initiative, which serves as an incubator for Kristang words. The name in itself is a portmanteau of jarding (garden) and linggu (language), and it serves to try to “Kristang-ise” words, things, and concepts we would see today, but do not have any such translations in Papia Kristang. Examples include “power plug”, “power socket”, and “electrical fuse”, which have proposed translations drawn from the Dutch language (stekker, contactdoos, and zekering respectively), as steka, tekdus, and sekering (also Malay sekering) respectively.

I have been keeping up with Kodrah Kristang in the years since, and the efforts are still going strong in Singapore. In fact, I have also used Papia Kristang as a topic for my entry in the annual Japanese Speech Contest organised by the BATJ when I was studying in London, and you can find the speech script and rough translation on The Language Website. Similarly, over in Malaysia, a language revitalisation effort has been spearheaded by the president of the Malacca-Portuguese Eurasian Association, Michael Gerard Singho, who also set up a language commission in Melaka as well.

Revitalisation efforts like Kodrah Kristang have not only spread awareness of the existence of Southeast Asia’s only Portuguese-based creole still spoken today, but also garnered interest in people who want to trace their Kristang heritage, and people who want to get involved, explore, or learn a language. If you are in Singapore and you want to get involved, I would definitely encourage you to give Kodrah Kristang a go. And if you are in Malaysia, more specifically Melaka, see if you can get involved in events in the Portuguese Settlement.

Further reading

Baxter, A. N. (1988) ‘A grammar of Kristang (Malacca Creole Portuguese)’, Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University.

Baxter, A. N. (1996) ‘Portuguese and Creole Portuguese in the Pacific and Western Pacific rim’, Atlas of Languages of Intercultural Communication in the Pacific, Asia, and the Americas. pp. 299–338.

Baxter, A. N. (2005) ‘Kristang (Malacca Creole Portuguese) – A long-time survivor seriously endangered’, Estudios de Sociolingüística, 6 (1), pp. 1–37.

Kodrah Kristang — Revitalisation project for Kristang in Singapore