Picture a typical language learning application. Things like Duolingo, Babbel, and Memrise would come to mind. These would prominently feature the languages with the most number of learners, major languages like English, Spanish, German, and French. But dig below the surface, and you would find some indigenous languages covered in there as well. On Duolingo you have Navajo and Hawaiian, and on Drops you have Ainu and Maori. Today, I want to talk about another online platform that houses indigenous languages. I have been made aware about this platform in January through Iḷisaqativut, a language school for the Iñupiaq language, a language which I have covered in this essay here. This is Doyon Languages Online.

The Doyon Languages Online is a platform part of the Doyon Foundation, a private foundation dedicated to enhancing the cultural and linguistic identity, as well as the quality of life, of Doyon shareholders, who are mostly of indigenous Alaskan descent. This name derives from the Yakut word for “master” or “chief”, тойон. Derivations are seen in the Deg Xinag, Koyukon, and the Lower Tanana languages, just to name a few examples, as doyon.

The Doyon region, according to the Doyon Foundation, encompasses a sizeable portion of central and eastern Alaska, though the Gwich’iin and Hän peoples may also be found in Yukon and the Northwest Territories of Canada. A number of languages can be found here but most of which are endangered, or at the brink of extinction. Thus, the Doyon Languages Online project aimed to revitalise these very languages, documenting, digitising, and promoting these languages to be learned by anyone who is interested. All 10 of its languages are available for free to learners, with the latest addition as of January 2024 being the Iñupiaq language. Being interested in indigenous languages lately, I decided to check this platform out, and explore yet more languages that many might not have ever heard about.

What languages are there?

With the exception of Iñupiaq, all the languages covered by the Doyon Languages Online platform are part of the Northern Athabaskan languages, which form part of the large language family called Na-Dené. There are 10 languages offered in total, which pretty much account for most of the languages spoken in the Doyon region of Alaska.

| Language | Branch |

| Benhti Kokhut’ana Kenaga’ (Lower Tanana) | Tanana-Tutchone |

| Deg Xinag | Koyukon |

| Denaakk’e (Koyukon) | Koyukon |

| Dihthaad Xt’een Iin Aanděeg’ (Tanacross) | Tanana-Tutchone |

| Dinak’i (Upper Kuskokwim) | Tanana-Tutchone |

| Dinjii Zhuh K’yaa (Gwich’in) | Kutchin-Han |

| Doogh Qinag (Holikachuk) | Koyukon |

| Hän | Kutchin-Han |

| Iñupiaq | Inuit, in the Eskaleut language family |

| Nee’aanèegn’ (Upper Tanana) | Tanana-Tutchone |

However, most of these languages are endangered at best, and extinct at worst. For example, Deg Xinag is reported to have only 2 native speakers as of 2020, while Holikachuk is currently extinct. Iñupiaq is perhaps the language with the most native speakers here, with under 2000 of them in total. With these concerning numbers, there is an imminent risk that Alaska will lose these languages in the near future, going the way of Holikachuk years prior.

Course structure

Courses are divided into units, and further subdivided into lessons. Before each unit, there are clearly defined learning objectives, giving users an idea of what to expect from the individual lessons. Some grammatical aspects are baked into each unit, often reflecting as informative slides in the lesson. Occasionally, lessons are also primed with cultural information about the people group that speak the respective language.

There are largely four types of exercises. To get acquainted with new words related to the unit, users are usually either presented with a sample conversation, or with a flashcard-style screen, where a word or phrase in the target language is shown with the corresponding English translation (and literal translation, if applicable). This is also complemented with audio recorded by the designers of the course, who are linguists or native speakers.

Next are two types of matching exercises. The first type of matching exercise one would encounter is the matching of word or phrase to the corresponding English translation. Per set, up to 5 pairs are given. Feedback is given only after all 5 matches are completed, before being able to choose between advancing to the next set of words, or retrying that set.

The other type of matching exercise cover the more audio side of things. Here, an English word or phrase is given, while each of the translation options play in sequence. Users are supposed to match the correct audio to the English word or phrase. If the user gets it incorrect, the prompt is repeated, allowing the user to retry. The reverse also applies, where an audio plays, and the user is supposed to match this audio to the correct English word or phrase.

Sometimes, rather than matching, users are prompted to dictate was is being said. This occurred to me in the Iñupiaq course, where I could choose between the letter options, or typing using the keyboard.

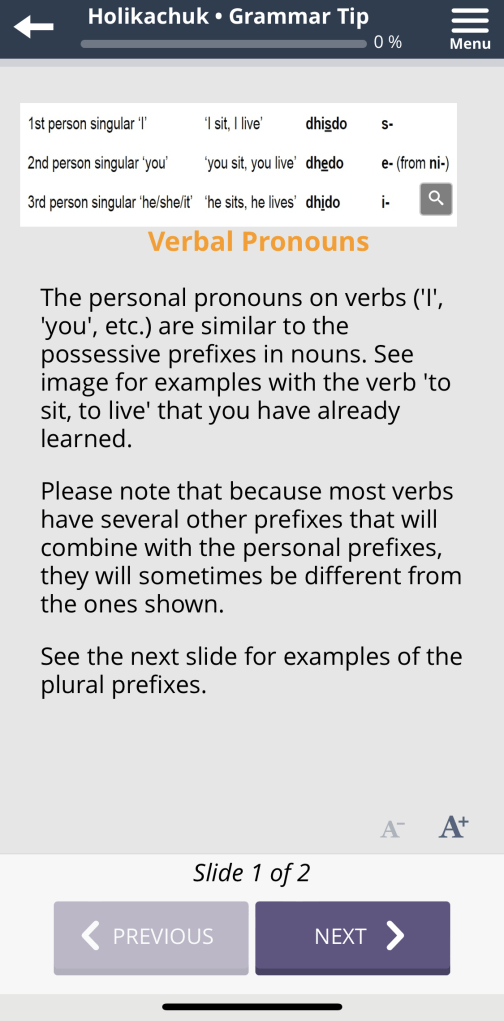

Finally, there are the grammar bits and bobs. In most cases, I do not find these grammar tips to be rather technical, and so, the lack of technical jargon would mean that these grammatical pointers could be more readily taken up by the learner, who might not typically have an understanding of certain linguistics terms.

Perhaps an interesting feature I observe across the languages offered on Doyon Languages Online is the display of audio waveforms for the recording. My best guess is to help learners distinguish vowel length, a phonetic feature that is distinguished between long and short vowels in the languages of the Doyon. Another benefit of this visualisation is, it could also help learners distinguish ejective consonants like “t’ ” from their plain counterparts like “t”. While they could sound similar to the untrained ear, the waveforms look a bit different, and it is this difference that is picked up by speakers of certain Doyon languages.

What I find inconsistent is, there are some courses that introduce the user to the alphabet and associated sounds, while others do not. This might be a little problematic especially if some sounds do not have English equivalents. While the recordings of words shown in the flashcards do help in understanding how the words are pronounced, it would have helped more to show the user the various letter or letter combination-to-sound correspondences. The Gwichʼin course, for example, had this feature, which allowed me to hear the difference between rather similar sounds like “ddh”, “tth”, and “tth’ “. However, the Holikachuk course lacked this introduction to the alphabet bit, and with rather scarce resources covering the language, learning how to speak it properly was considerably more difficult.

Perhaps a more minor inconvenience is the positioning of the keyboard during the dictation exercises on mobile. While these keyboards allow easy additions of certain letters with diacritics like ł, the keyboard is placed closer to the bottom of the screen than usual. On iOS devices, this could overlap with the area users would start the gesture to bring up the multitasking or switch to a home screen. Users of other devices might not have this issue, so it is a more minor point I would want to bring up here.

A potential improvement I would love to see is an end-of-unit review sort of idea, as a small means to test if the user has met all learning objectives in the unit. As there does not seem to be any spaced repetition or other forms of memory aids used in the exercises, I think that further improvements might need to ensure that the words acquired in the lessons are effectively learned by the user, or at least memorised.

We must note that for languages like these, this platform may be the only, or if not, one of the few online platforms available for interested learners to use to explore these languages. With the death of community-based or community-created courses on major applications like Memrise and Duolingo, the voices and words featured in these lesser-known indigenous languages would be more difficult to share with the world for all to learn.

Thus, I see the importance of the Doyon Languages Online platform to facilitate this process, as part of language revitalisation efforts for languages in the region. But there is also additional merit to allowing people from around the world to learn about these languages, and even explore the various words and sounds of these languages, without having to resort to conventional classroom methods. This platform is also a free and accessible resource to those who want to learn these languages, lessening the burden on the learner to search hard for textbooks or other resources to learn these languages.

If you are interested in exploring the indigenous languages of the Doyon region in Alaska, I cannot recommend the Doyon Languages Online platform highly enough. While there are some artefacts that might disrupt user experience, such as using the keyboard on its mobile application, the way the courses are structured provides an accessible learning curve, generally light on linguistic jargon, for users. Being able to record your voice for practice also helps with speaking, as many of these languages contain sounds that do not have an English equivalent.

Overall, the focus on indigenous languages by the Doyon Languages Online platform provides some hope for success in the ongoing language revitalisation efforts for these languages. I hope this review generates some interest in these languages, and further exploration of the platform itself.

The summary

Doyon Languages Online is perhaps the only language learning application freely accessible for users to pick up some Northern Athabaskan languages of Alaska, and the Iñupiaq language. The platform does adequately serve the means of learning a language through the methods mentioned, with clear aims, but kind of falls short when it comes to ensuring the unit objectives are met, such as through a unit review. The audio recordings feature waveforms that help users distinguish certain subtle articulations of sounds, though I hope the association between letter(s) and sounds are uniformly applied across all the supported languages in Doyon Languages Online. For now, I am giving this platform a 8/10, but I will be keeping up with this project in case more languages are added to the platform, or if significant changes are made.

| The good | The not so good |

| Primarily focused on indigenous Alaskan languages which are mostly endangered. | Inconsistencies in featuring how letters are associated with certain sounds. |

| Clear unit objectives to inform the user what to expect. | Lack of features to ensure these unit objectives are met by the user, apart from completion of exercises. |

| Audio recordings feature waveforms allowing users to distinguish certain sounds that have subtle differences. | Keyboard positioning might be a bit inconvenient in dictation exercises. |

| Grammar tips are light on jargon, allowing clearer communication to users who have no background in linguistics terms. |

The Language Closet rating (2024):

And for a final section where conflicts of interest would matter in the review, I have not been paid to make this review, nor am I currently affiliated with competitor applications to write reviews for applications like this. These opinions are entirely my honest thoughts about the features and changes present in the application.

i would personally really love to see this updated so that I could learn the language of my ancestors. It’s hard to find a place where I can learn the language of the King Islands but this is one of those few places but the app is out of date for new android devices

my family is the Killarzoac’s of Teller.

LikeLike