In December 2023, I came across several articles covering a journal publication with rather sensational titles. While some use more typical titles like “Climate Plays Role in Shaping Evolution of Human Languages, New Study Reveals”, others went the sensational route, using titles like “Languages are louder in the tropics” or “Linguistics study claims that languages are louder in the tropics”. While it is true that climate has an impact on the evolution of phonologies of human languages, such as phonemic tones and lack thereof, the claim that climate impacts how loud a language is seems a bit misleading. And so, I decided to read into this topic a bit more thoroughly.

These articles pertain to this study conducted by Wang et al., published in 2023 in a journal called PNAS Nexus, with the title “Temperature shapes language sonority: Revalidation from a large dataset”. At first glance, this study seems to build upon another study, albeit a smaller scale one, published in 2018 in the journal called Frontiers in Communication, under the title “Language Adapts to Environment: Sonority and Temperature”. In both studies, the respective researchers aimed to study the relationship between climatic variables like temperature and the sonority of languages.

However, how might one defined sonority in the linguistic context? Its definition does indeed point towards loudness in speech, but a more specific definition is the relative loudness of sounds in speech compared to other sounds of the same pitch, length, and stress in the same environment. And so, when we define what a sonorous sound is, it would be a sound or phoneme that stands out more prominently, i.e. less prone to being masked by environmental ambience noise, compared to other sounds. With this definition in mind, I could go on to explore how this is affected by climatic variables.

As Maddieson pointed out, this seems to be one of the implications of the “Acoustic Adaptation Hypothesis” or AAH, which has been explored in bird song. But the summary of this hypothesis is, a speaker’s sounds would want to be received by a listener, ideally with as much fidelity as possible. However, the environment is filled with obstacles that would filter or mask sounds, making certain sounds more difficult to stand out in the environment than others. And so, to adapt to these environmental obstacles, human language would employ sounds that would stand out in those environments. And so, one would expect that in environments that tend to filter or mask more sounds, the languages spoken there would have a higher proportion of sonorous sounds.

So, what makes a sonorous sound sonorous?

There are possibly two main criteria in what makes constitutes a sonorous sound. The first is the amplitude, basically how large the sound wave is from zero to peak (peak amplitude), or peak to peak (peak-to-peak amplitude). Sounds that produce a larger amplitude are louder than those with smaller amplitudes. The second criterion is the likelihood of masking by environmental noise. Sonorous sounds are more likely to vibrate air particles to reflect those sounds despite ambient noises, making them less likely to be masked by the environment.

When we analyse the various phonemes languages have, we can build a hierarchy of what the sonorous sounds are. At the top, we find the vowels, in descending order of sonority, low or open vowels, mid vowels, high or close vowels, and the glides /j/ and /w/. Below the vowels, we find the consonants. The most sonorous consonants are the flaps like /ɾ/ and laterals like /l/. This is followed by nasal consonants like /n/, and then by the fricatives like /v/ and /f/, and at the bottom of the hierarchy, we have the plosives like /b/ and /k/. Voiced consonants are more sonorous than their voiceless counterparts.

Putting this hierarchy into practise, however, we find no true consensus on how sonority is practically measured when we analyse entire words. This is partly due to the difficulty in quantifying sonority in segments of a word, and how sonority is averaged throughout a word. Some studies tend to use the vowel index, due to the fact that vowels are more sonorous than consonants, and so a higher vowel index would mean higher sonority, while others split sounds into categories from which sonority could be calculated. In the Wang et al. (2023) study, the researchers used the sonority hierarchy mentioned, but with a few changes here and there to reflect the index referencing American English. Using this index, a scale was created, with the least sonorous sounds scoring lower, and the most sonorous sounds scoring a maximum of 17. This means that sounds like /k/, /t/, and /p/ receive a score of 1, while sounds like /a/ have a score of 17. This is in contrast to Maddieson’s study, where a more dichotomised categorisation was used to classify these sounds, using the label “sonorant” or “obstruent”.

Derivation of sonority scores differed between the studies. While Maddieson focused on the duration of speech samples in the data that used sonorant sounds, Wang and the team split words into phonemic segments, assigning the index scores to each segment, whilst ignoring additional qualities of sounds such as nasalised vowels, palatalisation, and velarisation. However, prenasalisation of consonants was taken into account. The mean sonority index of a word was calculated by taking the mean index scores of the phonemic segments, which meant that each segment was given equal weight.

With a scoring system to work out the measurement of sonority, let us take a look at the type of data that were used in the respective studies. Maddieson used brief recording samples from 100 languages, which have their own drawbacks due to the quality in which the recordings are taken. For one, the content of these recordings focus on religious material, leading to the introduction of non-indigenous names of people like Jesus, which could introduce a “foreign accent” bias in the data. Furthermore, these recordings could also have ambient noise from background music or environmental sounds, though it was claimed that the signal-to-noise ratio was decent in most recordings. These recordings were noted to be edited, which could have omitted certain utterances due to truncation.

Wang’s study, on the other hand, used a collection of basic word lists from 10 168 doculects as documented on the Automated Similarity Judgment Program (ASJP) database, excluding those from creoles, pidgins, reconstructions, and constructed languages. While a 100-item Swadesh list was used as a standard for these word lists, a subset of 40 items was taken in the ASJP database. Even amongst this subset, there are some doculects in which less than half of the entries were complete. For these doculects, they were omitted from the study. This resulted in data available for 5293 languages as defined by the ISO 639-3 standards.

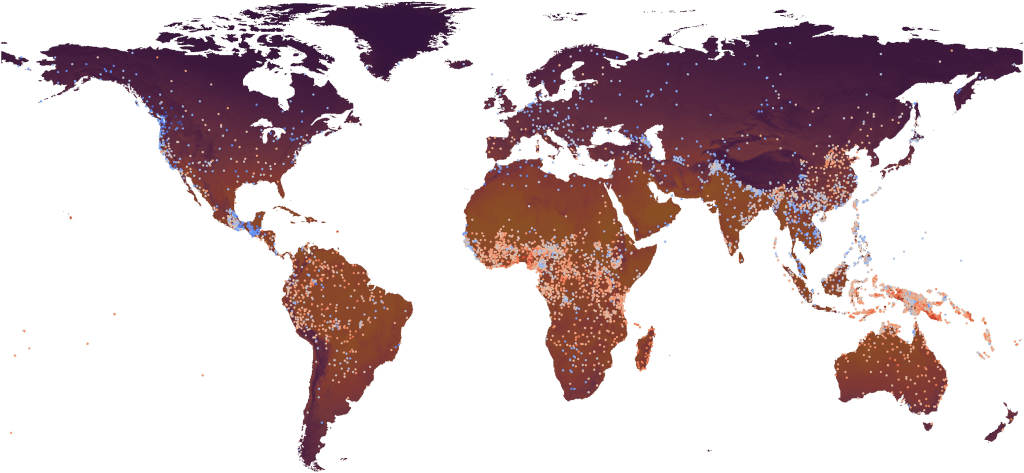

Both studies arrived at similar findings, but as Wang et al. looked at a majority of the languages around the world, they were also able to present a geographical distribution of languages by their mean sonority index scores. What they noticed was languages with higher mean sonority index scores tended to cluster around the equator and the subtropical latitudes in the southern hemisphere, while higher latitudes in the northern hemisphere tended to have languages with lower mean sonority index scores. The authors noted several exceptions, such as lower mean sonority index scores in Central America and South and Southeast Asia, the former tending to have consonant clusters, while the latter tending to have loose consonant clusters. These features have been argued to lead to lower mean sonority index scores.

Nevertheless, both studies reported positive correlations between sonority and temperature, meaning that the warmer the region is on average, the more sonorous the languages spoken there would tend to be. Wang et al. also reported a negative correlation between sonority and temperature ranges, meaning that the less varied the temperature is across a year, the more sonorous the languages spoken there tend to be. This is notable, given that the tropics tend to have little variation in temperature, while more temperate and polar areas have greater variation in temperatures across the year. However, Maddieson also studied addition environmental factors, such as elevation, roughness of terrain, and precipitation. He reported significant correlations between elevation and rugosity and sonority, but these environmental factors are collinear, as terrain roughness tends to increase the higher up you go. There was no significant relationship identified between precipitation and sonority though.

One factor that was omitted in these studies was the consideration of ambient air humidity or relative humidity. Being a major climatic factor, one must ask why this is omitted from analyses. This is likely because temperature and relative humidity are inversely related, as warmer air tends to hold more water vapour than colder air. This could have led to some sort of statistical multicollinearity, which would introduce some sort of confounding bias. However, why this factor is omitted from literature is not really reported, although Wang et al. noted previous studies have found a positive correlation between humidity and vowel ratio.

So, how might temperature be linked to sonority? There are two general proposed mechanisms — one physiological, and one acoustics. From the physiological perspective, cold air is usually dry because of its inability to hold much water vapour. This means that the vocal cords would be more susceptible to drying out when exposed to cold air due to evaporation, which somehow leads to a difficulty in controlling phonation. When combined with wind chill under cold conditions, the projection of sonorous sounds, which typically involve the vibration of vocal cords, would be disfavoured. One further behavioural mechanism proposed is the tendency for people to stay indoors under cold conditions, where individuals are communicating at close proximity. This tends to favour less sonorous sounds. Together, this would imply that cold climates tend to disfavour the prevalence of sonorous sounds like vowels, in favour of the less sonorous ones like voiceless consonants. This also incentivises the use of consonant clusters, which are linked to lower mean sonority index scores in words.

From an acoustics perspective, however, we see temperatures affecting the efficacy of sound projection across distances and frequencies. At higher temperatures, the higher frequencies of human sounds are more likely absorbed by the environment, leading to lower fidelity transmitted at higher frequencies compared to lower frequencies in warm climates. Additionally, there is also the consideration of turbulence in the air at warm temperatures. These can disfavour the projection of less sonorous sounds and sounds that have higher frequencies like sibilants. More sonorous sounds like vowels would be favoured, as most of them can be identified by low frequency waveforms, leading to the reduced likelihood of being masked or distorted in warm temperatures.

Another proposed mechanism ties in the relationship temperature has with elevation. Briefly put, temperatures get colder the higher up you go. The rate at which this happens is referred to as the lapse rate by Wang et al.. With warmer air and low altitudes, sound travels faster but bends upwards, resulting in a less efficient projection of sounds over horizontal distances. To account for this, sonorant sounds are more likely preferred.

Together, both studies lend support to the AAH Maddieson introduced with, as an extension to encompass human languages. However, there are some considerations in what we could infer from these findings and conclusions. Perhaps the most important consideration is the emphasis that the environment shapes languages, rather than languages adapt to the environment that the AAH seems to literally imply, as warmer climates would limit the prevalence of less sonorant sounds, while colder climates would limit the prevalence of more sonorant sounds, as noted by Wang et al. Colder climates are also more likely to exert an influence on sonority in human languages than warmer climates.

The other consideration lies within the time scale of the evolution of human languages. The authors noted that when relationships are studied between temperature and languages within a language family, like Austronesian, for example, this correlation seems to dissipate. We must note that changes in a language’s structure such as its lexicon and syntax are usually slow to occur, sometimes even being rather conservative. This could also apply to sounds, as sound changes could be resistant to change even under environmental pressure. Such a phenomenon is observed regardless of the range of language families, which could potentially straddle multiple ecological areas. However, Wang et al. noted a tendency for populations to spread within climatic areas rather than between them. However, Maddieson argues otherwise, proposing that sound changes can occur in spans of even a single generation, suggesting a rather malleable sound system in human languages. Instead of being resistant to change, Maddieson argues that changes in sound systems could persist in human languages over long periods of time. With this conflicting argument regarding evolution of human phonologies, I still have questions over the tendency for environmentally based or sociologically based sound changes in the short and long terms.

To circle back to the more sensationalised title, are languages really louder in the tropics? Having dived deep into these studies, I think this is quite misleading. If we define sonority strictly by decibel-based metrics of measurement, then I am inclined to answer ‘not necessarily’. However, if sonority is defined by the tendency of sounds to be masked by the environment, i.e. how a sound would stand out amongst environmental noise, then I would say ‘very likely’.

Perhaps one of the difficulties in making such science communicable to the general audience is the translation of technical lingo, which might not have sat well for the case of translating ‘sonority’ to just plain ‘loudness’, and ‘high mean annual temperature’ to ‘tropics’. For the latter, we have seen exceptions in languages spoken in Southeast Asia, which encompasses regions that lie within the tropical latitudes such as the Malayan Peninsula.

Regardless, these studies shed light on the role of the environment in shaping even the fundamentals of the world’s languages are built on, and as we have seen here, the sonority of words in human languages. When taken further, it could inform us how environments might have been for speakers of predecessor languages, or perhaps vice versa, if we are presented with climate data about our deep history.

Further Reading

Wang, T., Wichmann, S., Xia, Q. & Ran, Q. (2023) Temperature shapes language sonority: Revalidation from a large dataset, PNAS Nexus, 2(12), pgad384. https://doi.org/10.1093/pnasnexus/pgad384.

Maddieson, I. (2018) Language Adapts to Environment: Sonority and Temperature, Frontiers in Communication, 3, 28. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2018.00028.