When this topic pops into mind, our first instinct may be to gravitate towards English, French, and Spanish, the dominant languages in this region. French and English are spoken in Canada, English and Spanish are spoken in the United States, and Spanish is spoken in Mexico (North America largely includes only the Northern Mexican states, while the southern ones are grouped under “Central America”). But this is an oversimplification of the actual diversity of languages spoken in North America. As behind these languages, lies a wealth of indigenous languages long overshadowed by the popularity of the languages introduced to North America by means of colonisation, conquest, and immigration.

We have covered some of these languages individually, from the time I dove into Inuktitut way back in 2017, to the post series on the writing systems used in North America today. Some of the most well-known languages are Navajo (Diné Bizaad), Cherokee (Tsalagi Gawonihisdi, ᏣᎳᎩ ᎦᏬᏂᎯᏍᏗ), and the Inuit languages like Inuktitut (ᐃᓄᒃᑎᑐᑦ). The current state of these languages varies widely; some of these languages are extinct today, while some are thriving with thousands of speakers still regularly using their respective languages.

Today, I want to briefly introduce the diversity of indigenous languages in North America. For the purposes of this introduction, we will define North America to include Canada, the continental United States, Northern Mexico, and Greenland. In this region alone, there are almost 300 indigenous languages identified, though a significant proportion of which are dying or already extinct. This draws a parallel with the linguistic diversity of Australia, with a similar magnitude of linguistic diversity, and the current state of indigenous languages.

But where do we start? There are some two dozen language families in North America alone, with several more language isolates or languages yet to be classified, or even attested. There are regions of high language diversity in North America as well. In fact, the classifications of some of these languages are quite tenuous as they might group certain languages based on apparent geography rather than some form of phylogeny. One example of this is the subdivision of the Uto-Aztecan languages. Its immediate subdivisions are the Northern and Southern Uto-Aztecan languages, which are indeed separated by geography. However, establishing a phylogeny between these branches of Uto-Aztecan languages is difficult, resulting in debates over the validity of such a classification. Nevertheless, it is the Northern branch of the Uto-Aztecan languages that is found in North America, while the Southern counterparts (which includes Nahuatl) are found further down in Central America.

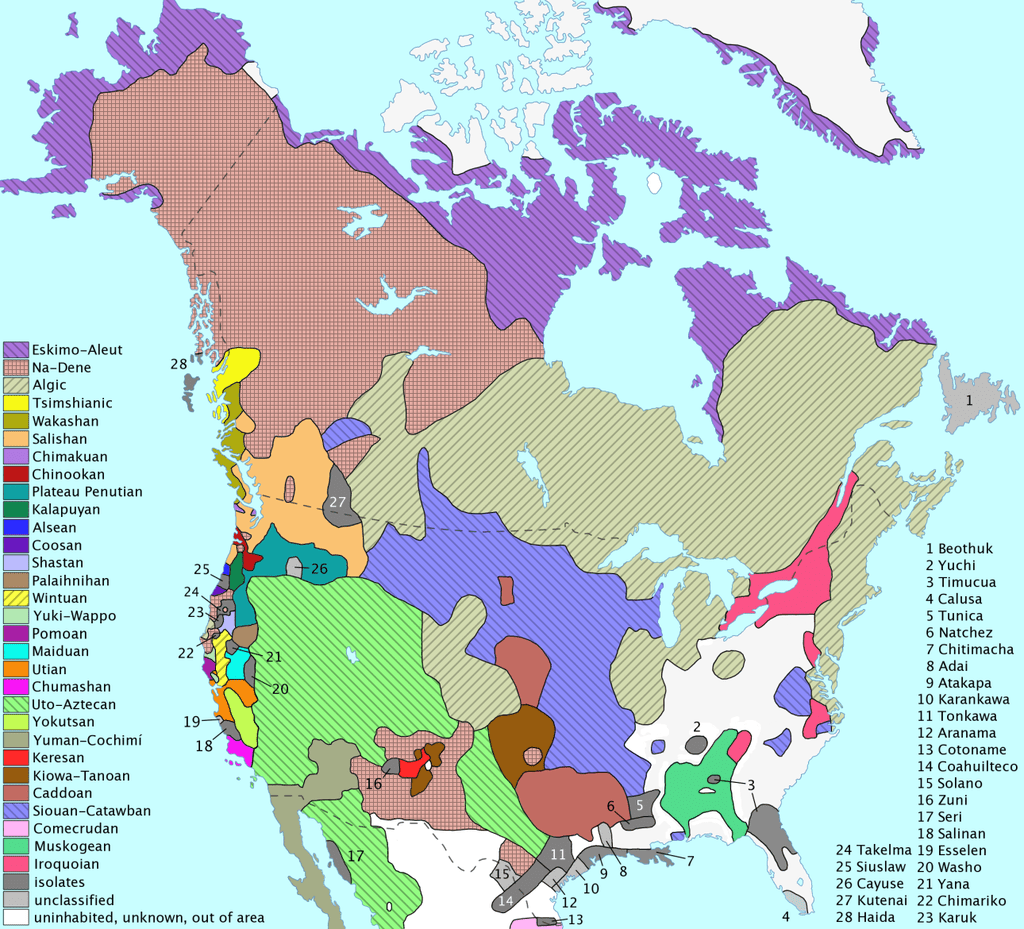

Perhaps we will start with the geographical distribution of these languages and their language families. Geographically speaking, the largest distributions of the indigenous North American languages are the Algic (including the Yurok, Wiyot, and the Algonquian languages) and the Na-Dené (which includes Navajo) languages, with the Siouan-Catawban, Uto-Aztecan, and Eskimo-Aleut languages not far behind. But the states and province along the Pacific coast, California, Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia, have a remarkable diversity of languages, forming an area of high linguistic diversity with more than 70 languages spread across 18 language families or more.

The map of the indigenous languages of North America prior to European contact. CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=147033

Unlike the languages of Australia, the languages of North America do not really have an identifiable pattern of sounds used in their phonological inventories. Perhaps one loose pattern I can find is that North America does not really have many tonal languages, and in the languages that do, some of them do not really have elaborate systems of tonality unlike their neighbours further south in Central America. Take Navajo, for example. It has both high and low tones, but that is pretty much it. In fact, linguists are debating is Navajo is indeed a tonal language rather than a pitch accent language, the system Japanese uses. But some Iroquoian languages do have tone, with Cherokee having as many as 6 tones.

Although the grammars of the indigenous North American languages vary widely as well, many of them seem to have a polysynthetic morphology or agglutinative morphology of varying complexities. The Eskimo-Aleut languages like Central Alaskan Yupik and Iñupiaq are known for their polysynthetic morphology, where a single word can contain multiple morphemes, and even translate to a complete sentence. Navajo, on the other hand, is an agglutinative language, relying on a lot of affixes but joined in such a way that interpreting them in segments is extremely difficult. Navajo might even be a polysynthetic language as well, according to some linguists.

When we talk about the controversial side of linguistics, perhaps one language of particular note is the Hopi language. If this sounds familiar, it would be because of its use as an example for the argument of linguistic relativity, a concept that is synonymous with the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis. When applied strongly, this becomes linguistic determinism, where languages determine human thought and perception of the world around them. This is because of Hopi’s use of adverbs and verbs to express the concept of time, or at least that is what was proposed by Benjamin Lee Whorf. Unlike English, Hopi lacks grammatical constructions that would translate to our understanding of time. This argument led to misinterpretation, debate, and controversy, with the most prominent one being the misconception that the “Hopi have no concept of time”. Since then, there have been linguists taking up each side of the debate, with one of the most famous critics against the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis being John McWhorter.

So far, we have only had a taster of the diversity and some prominent patterns or features of the indigenous languages of North America. While we have been biased towards the more commonly spoken languages, these are the languages that are also better documented, or taught to younger generations. There are perhaps more North American languages that we never know existed, perhaps wiped out from European contact due to disease, or died out without any written record. One topic I want to explore next is, what drives this diversity of languages in North America. And thereafter, we could explore some, if not, as many of the language families on North America as we can.