Here in the Language Closet, we cover a lot about writing systems, and some interesting bits surrounding the way we read and write. But there is one phenomenon I was introduced to back in high school regarding the loss of ability to write because one is too used to typing on text input media like phones and computers. I have only heard about this phenomenon by its Mandarin Chinese term, which can go by 提筆忘字 (which translates to something like, lift pen, forget words) or 電腦失寫症 (computer-induced agraphia). It took me a while to figure out the English translation, and its coverage seems to be very restricted to a particular writing system, Chinese.

Looking further into this, I realised that this phenomenon is not limited to just China or in Southeast Asia (where I spent most of my schooling days). Japan also seems to have a similar phenomenon, partially shown by a couple of That Japanese Man Yuta’s videos, although an equivalent translation does not sound as idiomatic as the Mandarin Chinese counterpart. Translated roughly to 漢字をど忘れする “forgetting kanji characters”, Japanese speakers can also face this problem when they want to write a certain kanji character.

Growing up, I learned and familiarised with new Chinese characters, first simplified, then traditional, using this method called 習字 (literally learning words), a rote learning method that largely involves you writing a character or a word repeatedly to build muscle memory on how to write the character, including stroke length and stroke order. I presume that is the case for a great majority of Chinese learners, and Japanese learners for kanji, so that experience is far from unique. It sort of makes learning Chinese and kanji characters pretty time consuming, although it is possible that learning patterns and applying them for other related characters can take place. Researchers have also noted that this is a rather neuro-muscular affair, using various areas of the brain, particularly those associated with motor memory and handwriting.

So how does this phenomenon take place? Many sources seem to point towards technology, as typing steadily gained popularity. On computers and phones, input method editors (IMEs) are ubiquitous when typing words in Chinese and Japanese (and Korean). Romanised versions of the word are typed in, and the computer would convert them into a selection of possible words and characters one might be looking for.

In Chinese, this takes place by using the hanyu pinyin or bopomofo, and using abbreviated hanyu pinyin could also help yield desired characters. For example, take 圖書館 (library, 図書館 in Japanese). To type that out, one would just need to type the hanyu pinyin, tu’shu’guan, or bopomofo, ㄊㄨˊ ㄕㄨ ㄍㄨㄢˇ , to get the word. Alternatively, one just needs to type the first consonant of each syllable to yield that result (along with several more choices). For Japanese, the romanised toshokan is typed to yield that kanji, along with some grammatical variants.

This brings along many conveniences to speakers and users of these languages. From being easy and fast to type, to convenient as one does not need to recall the stroke order of the characters, how much IMEs and keyboards have done to streamline input of Chinese characters and kanji cannot really be understated. Typing these characters in would only typically require knowledge on what the character looks like, and what the character sounds like.

Therefore, it would seem logical that these conveniences would be to blame for the character amnesia phenomenon. Over-reliance on typing could erode muscle memory on writing these characters, leading to a memory loss of how to even begin writing a character. It was this hypothesis that was pushed onto me and fellow schoolmates back in high school, and one that has dominated Chinese discourse when exploring this phenomenon.

Studies investigating this could have perpetuated a technophobic discourse. However, little research has been done on the prevalence of ‘character amnesia’ in Chinese and Japanese language speakers, or even estimated when this probably began. Surveys in China have found that most people have reported having trouble writing some characters. How these samples were taken was anyone’s guess, but if these were to be believed, it would be an indicator of how prevalent this problem is in China. Surveys also made no mention on the characteristics of the characters one reported trouble writing in terms of frequency or complexity. However, a 2013 spelling bee on the Chinese state television CCTV showed that only 30% of participants could write the characters for ‘toad’, or 癞蛤蟆 (lài há ma).

Similar prevalence was not really studied extensively in Japan, although this problem seems to be compounded by the kanji list, and introduction of word processors. In fact, the phenomenon of ‘character amnesia’ associated with word processor use was so problematic, a Japanese term ワープロ馬鹿 or wāpurobaka (literally word processor idiot) was introduced. The 1980s in Japan saw a period of reform of the Japanese script, when the tōyō kanji system was replaced with the jōyō kanji, which contained 1945 characters (in contrast to tōyō kanji‘s 1850) in 1981, and when the Japanese Industrial Standards Committee attempted to standardise a kanji character set to be implemented in computing and word processors. Around 200 characters were simplified in the new character set, which contained 6877 characters in 1987. This meant that word processors had a character set several times larger than the character set one would have been taught in school.

However, character size differences would not have exclusively accounted for this phenomenon. An Asahi Shinbun article in 1985 reported that students faced difficulty in remembering how to write relatively simple kanji by hand since the introduction of the word-processor to a university in Isehara. A similar result was reported in 1993 by the Information Processing Society of Japan. Then again, this prevalence in Japan was not really studied. As a result, the true scale or magnitude of the problem could not really be established.

Another sticking point is, many of these studies seem to concentrate on Japan and China, with little coverage given to Chinese speakers in Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Malaysia, which are countries with substantial proportions of people who would use Chinese characters. Furthermore, I cannot seem to find coverage for Traditional Chinese characters; studies tended to focus on Simplified Chinese, which is predominantly used in China and Singapore. With the scarcity of studies and literature covering this phenomenon, there are many knowledge gaps present in this specific field of linguistics, and it is certainly one that would be of interest as some viewed that the Chinese characters were ‘endangered’ by technology.

This has led to other predictors proposed for this phenomenon. Victor Mair, a sinologist, remarked that character simplification could have played a role in character amnesia in China, as simplified characters do not have some clues provided by traditional characters for pronunciation and structure. Additional remarks also included the inconsistent simplification patterns of characters. One example in this post here in the Language Log compared differences in certain elements of characters between simplified and traditional forms.

One comparison involved 陽 (yáng) and 湯 (tāng), which were simplified to 阳 and 汤 respectively. Comparing the elements, it could be likely that the right-hand component could have provided a phonological clue (-ang final) to its pronunciation. Additionally, they also remarked that the simplification of the character of ‘leaf’, 葉 to 叶 gave no clue to the traditional form. It is bizarre, since the radical on the traditional character, 艹, gave a semantic indication that the character is related to a plant, while the radical in the simplified character, 口, indicated something to do with the mouth.

However, this is not the case for ‘surprise’, written as 驚嚇 (jīng xià) and simplified to 惊吓. Here, the 京 and 下 in the simplified forms, pronounced jīng and xià respectively, give more apparent phonological clues compared to the traditional counterparts.

One study by Huang et al. in 2021 tried to examine predictors of character amnesia in Chinese university students, and was the first large scale study for empirically understanding character amnesia in a specific demographic. Asking each participant to handwrite 200 Chinese characters that were randomly sampled from a set of 1600, the researchers found that there was character amnesia for 42% of the characters, and 6% of the time for these university students.

When building a model to examine the predictors of character amnesia, the researchers looked at 14 character-level variables. Among which are count frequency, or how often a given character appears in a corpus, age of acquisition, imageability, familiarity, and stroke count. No analysis on technology use or how often one types instead of writes was conducted, however. They found that character frequency, age of acquisition, spelling regularity, familiarity, stroke count, and imageability were significant predictors of character amnesia.

Some explanations seemed quite reasonable. Rarer characters would be more likely to be erroneously recalled, if at all, compared to more common characters. Similarly, characters learned at an earlier age would have stronger and more consolidated connections between semantics (aka meaning) and phonology (aka sound), allowing easier retrieval from memory when that character is required. Furthermore, the authors also found that characters used in more foreign contexts are more likely to be forgotten. Interestingly, the researchers found higher character amnesia in characters with more strokes than those with fewer strokes. Many simplified Chinese characters generally have fewer strokes than their traditional counterparts, and it would be interesting to compare them.

Characters with a lower spelling regularity are more likely to be erroneously recalled. Without radicals that can indicate how the character is pronounced, the more likely a character gets wrongly recalled. Examples include variants of the syllable qing, which could conjure this radical 青. But for characters like 灶 (zào), which constituent radicals are 火 (huǒ) and 土 (tǔ), regularity here would be rated low as neither constituent provides a phonological clue in the character as a whole. Characters like these could be more likely to be misremembered.

But where this study is restricted is in what their findings represent. Their sample of participants included only university students who use simplified Chinese, and so findings can only apply to that particular demographic. Working adults and retirees, who may have different frequencies of being required to handwrite or type Chinese, would undoubtedly have different prevalence of character amnesia. Nevertheless, this study is a first in understanding the phenomenon of character amnesia, and could be extended to investigate further factors like sex, age group, and highest attained education level, or be used to study character amnesia in handwritten traditional Chinese. This could build a bigger picture of character amnesia in the sinosphere, which can have pedagogical implications to help future generations better retain memory of the characters they learned during their formative years and thereafter.

Others might point to hanyu pinyin, which is the predominant form of IME input for China (Taiwanese users might primarily use the bopomofo system). For characters one forgets, or does not know how to write, they could simply substitute that character for the hanyu pinyin version instead. Sometimes, a character can just be scribbled out, and replaced with the pinyin.

This habit could have been picked up early in school, when one learns the pinyin before moving onto characters. Kindergartener me could attest to this. When writing in Chinese, if one could not produce the character they need, they were allowed to substitute it for the pinyin, and then learning the correct character as a “correction”. This was more often the case for essays, as we, as students, were required to turn in an essay above the word limit in a time limit. Weaning off this juvenile habit required a little push, by marking down on cases where pinyin was used instead of the needed character, and a little pull by allowing the use of paper dictionaries, or sanctioned electronic dictionaries for the examinations. This took place when I was 10 or 11, which was a memorable time for me with electronic dictionaries because I was obsessed with the glitches it had. And to be marked down for using pinyin in advancing years of education was rather humiliating since it was (and to my knowledge, still is) a waste of marks that could be the deciding factor between certain score bands. Couple this with the Asian parent stereotype and you might see where this is going.

However, for some, this habit still stuck on, as the pinyin served as a handy and convenient phonetic option to fall back on in case a memory block surfaced. The issue remains though, as there is no empirical studies on how often or how prevalent this is indeed the case. But there would be some who believe the pinyin is a ‘threat’ to Chinese characters, or even Chinese culture altogether.

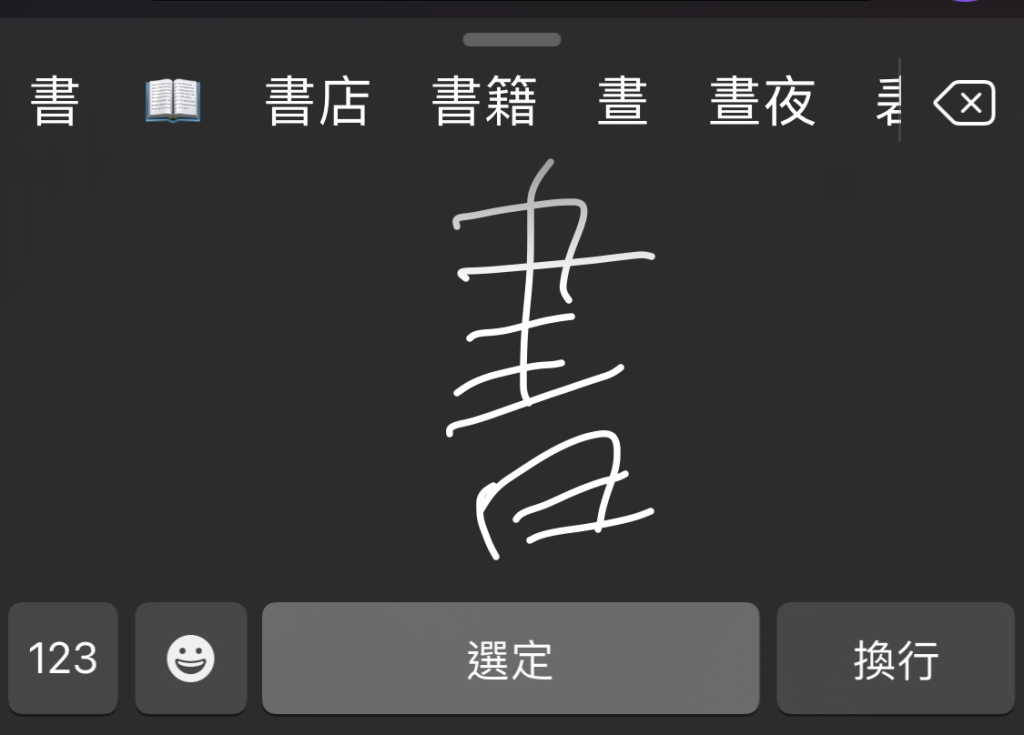

Ironically, as much as a technophobic narrative some sources seem to push when discussing character amnesia, technology can also serve to help retain this muscle memory built up from lessons. Handwriting recognition like those implemented in smartphones allows a user to input a character by writing it stroke for stroke, with some allowances for stroke length and proportions (as you would see in the picture above). Although slower to input than typing, it still forms a need for the user to apply their muscle memory into actually writing (hence inputting) a character into a computer or phone. Handwritten input remains to be my primary form of digital input for my smartphone and tablets, and this seemed to have helped retain some memory of how these characters are written. Perhaps this would make it more difficult to forget how to write certain characters a person has learned over the course of their education.

At the end of it all, I am left with more unanswered questions. What is the prevalence of ‘character amnesia’ today? Is it a greater cause of concern today due to technological advancements? Does a strong technophobic bias still exist in addressing this issue? Is technology really to blame, or is it something else, or a combination of these? On some platforms, there are some opinionated stances that could present as hyperbole, but without a reliable reference point, the extent to which these claims are biased or exaggerated could not really be elucidated. But it could be true that technology is what propelled Chinese characters to be convenient to learn or write, or more rather, type, but also, in the process, eroded that very ability to write.

Further reading

- Professor Victor Mair’s contributions to the Language Log https://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/index.php?s=character+amnesia

- Hilburger, Christina. “Character amnesia: An overview.” Sino-Platonic Papers 264 (2016): 51-70.

- Huang, Shuting, et al. “Character amnesia in Chinese handwriting: a mega-study analysis.” Language Sciences 85 (2021): 101383.

- Almog, Guy. “Getting out of hand? Examining the discourse of ‘character amnesia’.” Modern Asian Studies 53.2 (2019): 690-717.

Pingback: סינית אני כותבת אליך | דְּבָרִים בִּבְלוֹגוֹ

Pingback: creative-commons

Pingback: I Used to Know How to Write in Japanese - America’s News. 24/7.

Pingback: I Used to Know How to Write in Japanese - Solutons Lounge