The vast majority of languages have something in common with each other — in their canonical word order, the subject always comes before the object. Such word order encompasses the subject-object-verb word order, the most common word order accounting for 45% of all the world’s languages, subject-verb-object word order accounting for 42% of the world’s languages, and the verb-subject-object word order (like Welsh and Arabic) accounting for 9% of the world’s languages. Adding these together, these three word orders make up 96% of the world’s languages, leading to some early modern linguists to postulate that the subject coming before the object is a form of linguistic universal.

What they missed out on is the remaining 4%, where the object comes before the subject in their canonical word orders. Here, we would find languages like Malagasy, which follows a verb-object-subject word order. But among these word orders, the object-subject-verb (OSV) is probably the rarest, accounting for less than 0.5% of all languages. With sentences that can literally translate to, for example, “books I read”, one would be quick to associate such a word order with a particular character in Star Wars, Yoda.

There are some languages that may allow the OSV word order to place emphasis or mark the passive voice. Other languages are more flexible in word order, hence allowing the OSV construction in them as well. As such word orders do not necessarily dominate in usage in these languages, OSV is thus not the canonical word order of these languages. A common pattern of these languages like Korean, Japanese, Nahuatl, and Portuguese is, an OSV word order places emphasis on the object, by marking it as a topic like in Korean and Japanese. Passive constructions using OSV is commonly found in Mandarin Chinese, for example. Interestingly, Dyirbal was once noted to have an OSV word order, but it was later realised that it has a flexible word order, and that OSV is one of the permissible ones. Another fun fact is that some contexts of British Sign Language use an OSV word order as well.

Looking at the distribution of languages primarily using the OSV word order, we find generally two places where these languages typically cluster — the Amazon basin, and the island of New Guinea. Examples include Tobati in New Guinea, Xavante, Apurinã, Kayabí, and Nadëb in the Amazon Basin, and Kxoe in Namibia, Botswana, and Angola. These languages only have a few hundred to several thousand speakers each, with Kxoe having around 8000 native speakers. The extent of documentation and study varies as well, and as these languages are indigenous languages in relatively rural areas, we are more likely to find that these languages are relatively poorly studied.

But among these languages, the most famous one to be attested for its OSV word order is the Warao language. Largely spoken by the Warao people of the Orinoco delta, the Warao language has no genealogical relationship with any other language. In other words, Warao is a language isolate. With almost 33000 native speakers across Venezuela, Guyana, and Suriname, this is also perhaps the most widely-spoken language that has a canonical OSV word order.

Despite Warao’s current status as a language isolate, there are some limited efforts to try to establish some relationship with other languages. One such proposal is the Waroid family, proposed by Granberry and Vescelius in 2004. This attempted to link Warao with the Macoris and Guanahatabey languages once spoken in the Greater Antilles islands, using toponymic evidence in these languages to support their case. Warao has also had some influences from the languages it makes contact with the most — Cariban, Arutani, Sape, and Máku are among the languages which share some lexical similarities with Warao due to a proposed interaction sphere for these languages.

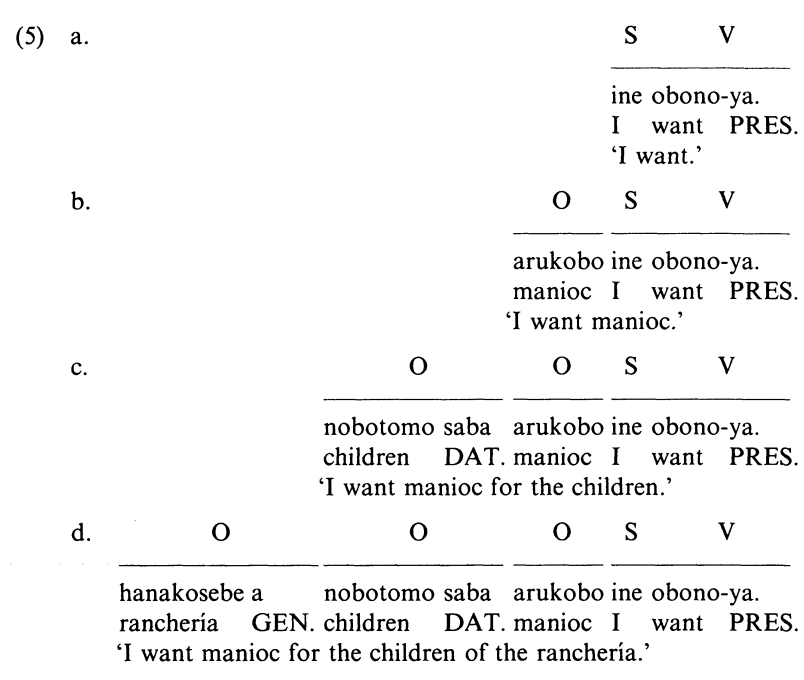

Warao does not have a particularly special phonological inventory. While small, with 11 consonants and 5 vowels distinguished by vowel length, Warao does not have unusual or rare consonants of note. In addition to its particularly rare OSV word order, Warao makes use of case particles to denote noun cases. The accusative and nominative cases do not seem to be readily marked for nouns, but the genitive case is marked by a, and the dative case is marked by saba. Obliqueness is indicated by the particle isiko. The usage for some of these cases are shown below:

However, with the rise of diseases and the expansion of industry into the Warao homeland, some Warao have been forced to relocate, seeking refuge in Suriname and Guyana, and some moving to Boa Vista in Northern Brazil. This brings up the problem of language endangerment. UNESCO has classified Warao as endangered, most likely due to the factors mentioned earlier. The Warao who relocate would also have to learn new languages to assimilate, possibly reducing the usage of their native language over time. Over time, we might observe a steady decrease in the number of Warao speakers if language preservation or revitalisation efforts are not done.

Further reading

Romero-Figueroa, Andrés (1985). “OSV as the basic order in Warao”. Lingua. 66 (2–3): 115–134. doi:10.1016/S0024-3841(85)90281-5