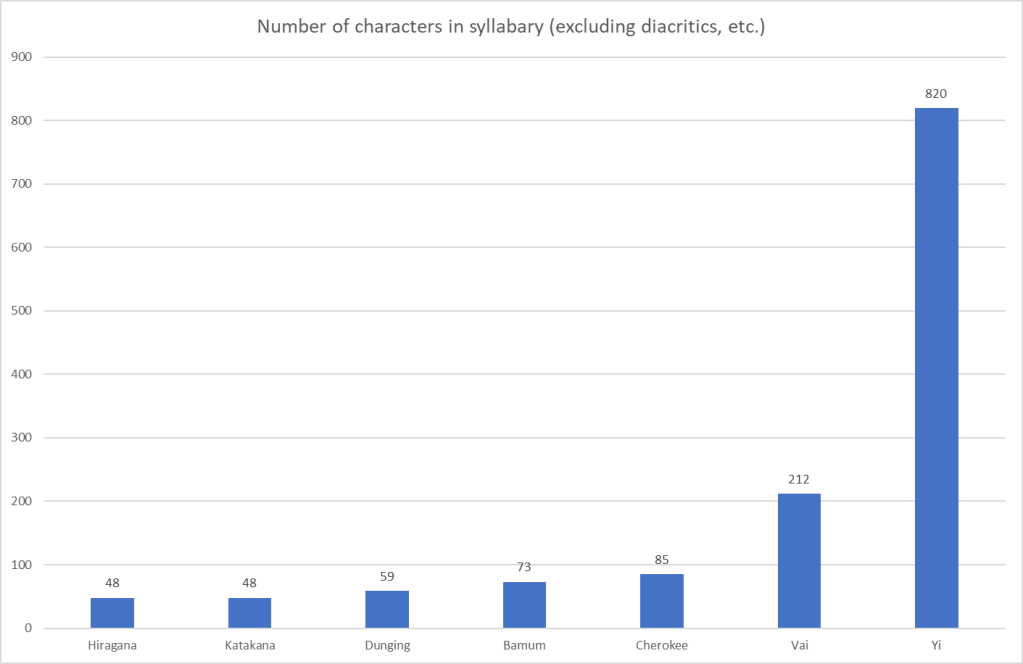

When we compare the number of characters in writing systems, we can see a rather distinct pattern. Alphabets and abjads generally have similar sizes, often numbering in the 20 to 30-odd letters. Coming in bigger than these are the syllabaries, which generally have anywhere from around 50 to 90 characters. And among the largest of all, are the logographic or ideographic scripts, with thousands of characters in use.

But even in the syllabaries, there are some outliers that push the limits of how huge a syllabary can feasibly be. Previously, and by that, I mean about 6 years ago by now, we covered the Vai syllabary, which has a total of 212 characters. While it is substantially larger than many other syllabaries we are more of less familiar, it is still greatly surpassed by one other syllabary, still in use today. Coming in at a whopping 1164 characters, plus an additional character, this syllabary is the largest to have ever existed, and be standardised for use. But this figure would come with a huge asterisk, which I will preface here.

Most of these syllabaries here do not encode tone, nor pitch-accent into them. But this one is different. Primarily used in the Yi and Lolo languages, this writing system perhaps stands out as unique for encoding tone together with the consonant and vowel combinations, with each possible consonant and vowel combination having up to three different forms, to encode for each of the tones these languages can have.

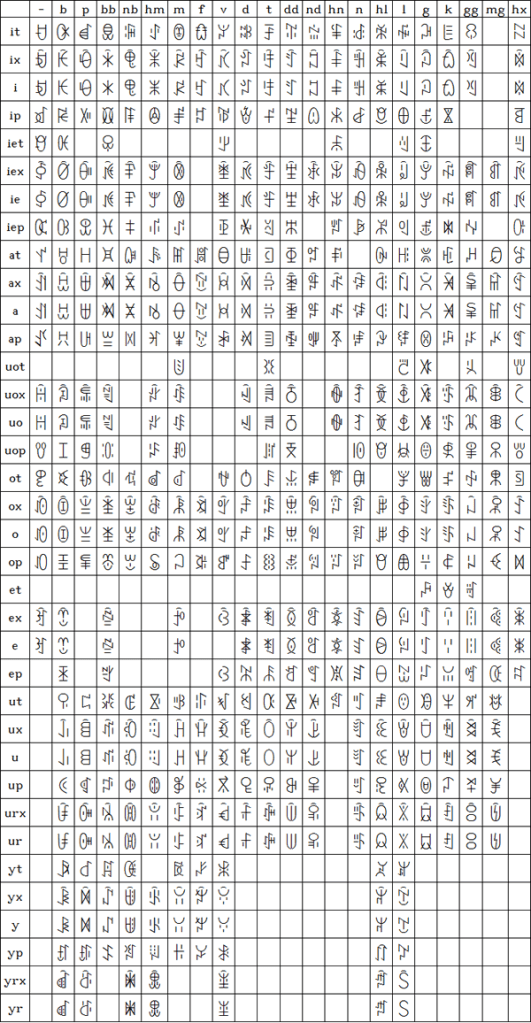

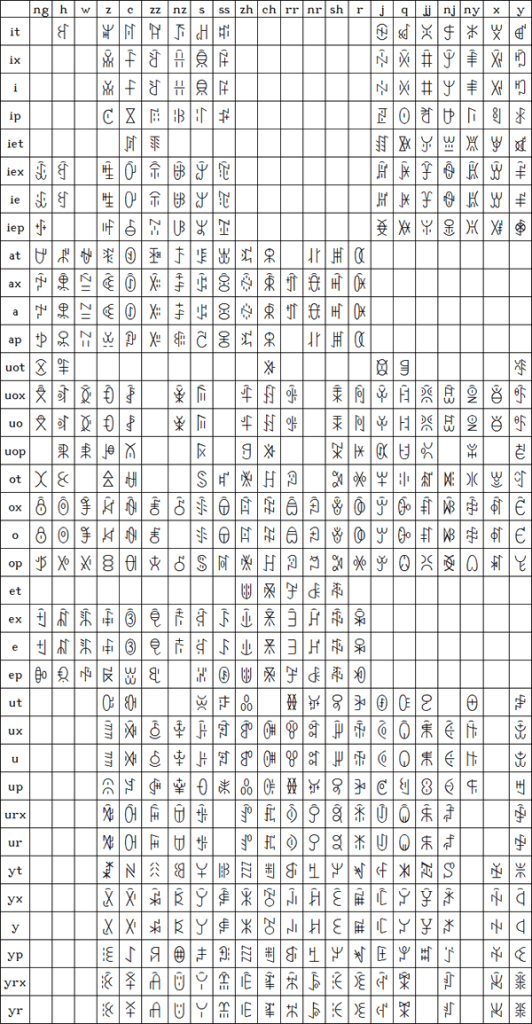

These tones are high (-t), mid, and low falling (-p), and a fourth tone (-x) which can be high-mid or mid falling depending on the variant. With 43 consonants and 10 vowels (with 2 of them being buzzing vowels), the Nuosu and other Loloish languages pack a sizeable phonological and tonological inventory, but with a weird quirk. They do not encode any diphthongs in their writing system, the Yi syllabary. Instead, each character is a unique combination of one consonant head, one vowel, and one tone. All of these produces a total of 1165 possible combinations of syllables, and by extension, that probably means that every book and publication out there is a “remix” of these syllable combinations.

Why does the Yi syllabary have this asterisk attached to this figure of 1165? Well, among these 1165 characters, 345 of them represent syllables that have the high-mid or mid falling tone, and is marked using a diacritic. Since in our comparison above, we do not consider diacritic use to be unique characters, these characters with diacritics on them would be omitted. This gives us a total of 820 unique characters in the syllabary. It is still almost 4 times as massive as the Vai syllabary, though, and this 345 characters with the diacritic on them also greatly exceed the syllabary size of Vai. This 820 figure also includes the syllable iteration mark ꀕ or “w”, which reduplicates a preceding syllable. Admittedly, this would also give the Japanese writing systems one more character for each of its 3 writing systems in its script, since there is one iteration mark for kanji, 々,hiragana, ゝ, and one for katakana, ヽ. Should we exclude this, then the Yi syllabary would have 819 characters.

What is interesting is, the Yi languages were not always written using the Yi syllabary. In fact, this syllabary is a rather new invention, dating back to 1974 by the local Chinese government, experimentally used in 1975, and officially adopted in 1980. This script was derived from Classical Yi, which is a syllabic logographic system consisting of thousands of characters, and depending on the manuscripts used in analysis, up to 90000 variations of different Yi glyphs or characters. This includes, quite bizarrely, the 40 different ways to write the word “stomach”. But this usage was largely limited to the bimo, who were the priests, or shamans or medicine men in Yi society. So, in a way, this syllabary, while massive, represented a great simplification of what was a clunky and unstandardised writing system, and provided accessibility for literacy and education in the Yi language.

The romanisation of Nuosu and Yi languages was also proposed in 1956, where the Latin alphabet was used to transcribe Nuosu sounds. This was where the tone endings mentioned earlier were derived from, and the transcription in the featured image above. Lastly, an abugida was also proposed by Sam Pollard, who devised the Pollard script for the Miao language which is still used to this day. For a language with a sizeable number of consonant-vowel-tone combinations, an abugida could have served a more efficient way of encoding these sounds for the writer, and decoding these characters for the reader. Perhaps a counterargument to this would be the cultural value of the Yi syllabary to the people who speak the languages that use it, although I have been unable to find documents surrounding the motivations or justifications for preferences for the standardised syllabary over an abugida.

For the approximately 10 million people who use the Yi languages, the Yi syllabary is thriving in its use. In Sichuan province, for example, there are street signs with Mandarin Chinese, Yi syllabary, and English printed on them. And if you do look around hard enough in Yi-speaking areas in Sichuan, you might come across books printed in the Yi syllabary, which can be a very bizarre sight in a country where Mandarin Chinese and the Chinese script can dominate discourse throughout. The Yi syllabary, without doubt, is one of the most intriguing syllabaries in the world, and pushes the upper limits on how huge a syllabary can get.

Pingback: The writing systems that resemble comics (Pt 1) | The Language Closet

I find Nuosu logograms super interesting, and they seem to be an underresearched topic as well. Do we even know how the logograms are read? And on the basis of what did they create the syllabaries in the 1970s? It seems like such a modern creation—were they at least based on the syllables present in the logographic system (a little bit like how Egyptian hieroglyphs gave rise to the letters of the Proto-Sinaitic script)?

This reminds me a little bit of the Tifinagh script, whose most recent iteration was actually introduced in the ’70s. We tend to think of it as super ancient, but it’s actually quite new… Although, unlike Nuosu, at least it didn’t change radically from a logographic system to a syllabic one…

LikeLike