Bungee jumping is an extreme sport. Typically occurring over ravines, canyons, buildings, or some form of high elevational difference, this activity involves free falling and rebounding whilst attached to an elastic cord. With its thrill, comes a lot of safety precautions today, but even those do not completely guarantee protection from injury or death.

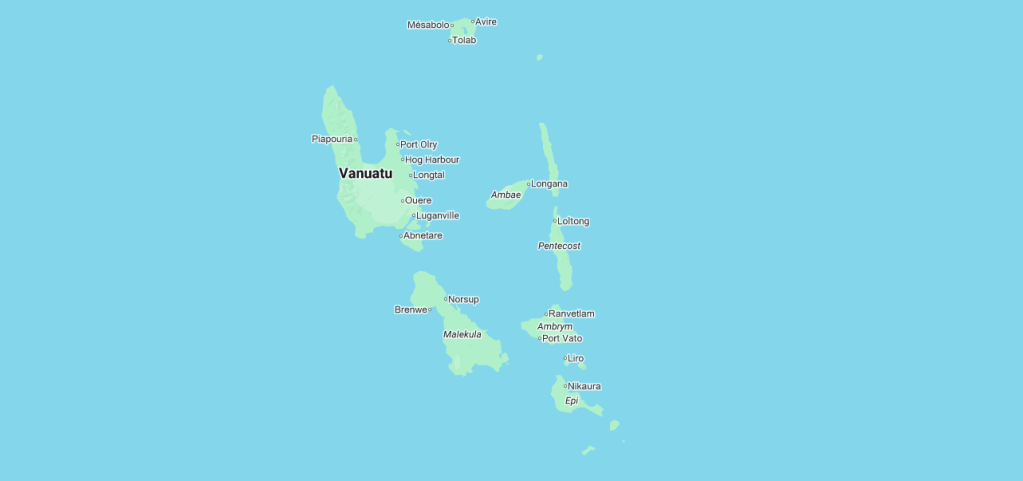

But what if this activity is dialed back to a more traditional, a more pre-industrial time, so to speak. This includes the stripping of nearly all safety measures in modern bungee jumping, and even the material of the cord used in the jump. This form of traditional bungee jumping is practiced on the southern parts of Pentecost Island in Vanuatu, known as land diving, or gol.

Gol, also known as Nanggol in Bislama, one of the official languages of Vanuatu, involves participants jumping off wooden towers with tree vines wrapped around their ankles. Predominantly performed by men today, gol is an annual ritual believed to bring great yam harvests, as well as certain health and strength benefits. Additionally, participating in the ritual also demonstrates masculinity and boldness, as men who refuse to dive one way or another are often treated as cowards. The language that gives this activity its traditional name is none other than the Sa (or Saa) language.

The Sa language is an Austronesian language belonging to the Oceanic branch. More precisely, Sa is part of the Central Vanuatu group of languages, though this classification is shaky as southern Pentecost is a transitional zone between North and Central Vanuatu branches of languages. Ethnologue also suggests Dlo Kêt as an autonym to refer to the Sa language, but I cannot find publications that refer to the language with this term. Omniglot’s entry suggested that Sa is ‘what’ in the language, while Lokit, possibly another realisation of Dlo Kêt, translates to ‘the inside of us all’.

Speaker numbers are difficult to estimate, as the last known figures place the number of natives speakers as of 2001 to be around 2500. Despite the small speaking population compared to many languages around the world, Ethnologue suggests that Sa is stable, and not necessarily endangered. This is likely due to the strong intergenerational transmission of the language to younger speakers, despite Sa’s general lack of presence or formalisation in institutions.

Despite this small speaking population, there is considerable dialectal variation. This can be attributed to differing cultural influences in Sa villages, such as Western education and Christianity, as well as indigenous cultures and traditions known as kastom in Bislama, and lon duan in Sa. The northern and southern varieties are considerably different from the eastern and western counterparts, such that they are not entirely mutually intelligible.

One example is how the paucal pronouns, basically pronouns used to refer to a group of a few people or things, are formed in the varieties used in villages like Lonbwe, compared to other varieties. In the Lonbwe dialect, these are formed using the number ‘four’, pat, as in mapat (literally we four), while others are generally formed with the number ‘three’, tēl, as in matēl (literally we three). There are also dual pronouns (referring to two people or things), but their variation is not as stark as the paucal ones. Additionally, like many Austronesian languages, Sa distinguishes between the inclusive and exclusive ‘we’, with the plural forms being kê(t) and gema respectively.

Interestingly, Sa has two different forms of possession. One (na-) denotes the possession of general belongings, while the other (a-) is more specifically used for food items. However, a single food item, like a fish, may be treated as either a food item or a belonging. Verbs are subject to a lot of modification with prefixes and suffixes, much like what we see in Malay and Indonesian. These reflect a lot of grammatical functions, such as the hypothetical, -po, and even a transitive verb marker -nê.

Sa phonology is noted to contain seven phonemic vowels each distinguished by length, and around 18 or 19 consonants depending on the dialect. For instance, northern varieties tend to have the /f/ sound, and the ‘s’ sound might be pronounced as /ʃ/ instead. Southern varieties, on the other hand, would tend to use the /h/ sound to replace ‘s’. Stress usually falls on the second-last syllable of the word, but can fall on the last syllable if the word ends in a consonant or a long vowel.

One of the most salient results of varying influences on the dialects of Sa is how numeral systems work in the language, as well as the various dialects. Garde’s 2015 publication goes further into detail on numeral systems in Sa spoken in kastom villages, and makes comparisons with more Christian- or Western-influenced settlements. Some interesting remarks were made on how kastom villages counted money, the Vanuatu vatu, in comparison to more Western ones. As the vatu includes denominations from 100 into the thousands, something that is otherwise generally too large to practically count, there would be some compulsion to use Bislama numbers instead. However, Kastom villages tend to use terms borrowed from colonial currencies, notably shillings (selen) and pounds (pon). One selen would be equivalent to 10 vatu, while a pound is 200 vatu. Beyond 20 000 vatu, there is a Bislama loanword (andred [su]), as well as the verb ma-mrôp su or môrôban su, with 200 000 vatu being taosen [su] with the Bislama loanword, as well as the Sa word ma-mtar su. Non-kastom villages, however, tend to use the Bislama forms entirely.

There is also a set of decimal numbers and imperfect decimal numbers in the Sa language, and the contexts in which each system is used can differ from variety to variety. What imperfect decimal numbers are is a system of number terms from 1 to 10 where the terms for 6 to 9 are constructed as some form of compounds of simpler numbers such as 5 + 1 or 10 – 1.

| Number | Sa decimals | Sa imperfect decimals |

| 1 | wantua | su |

| 2 | urua | ru |

| 3 | teul | tēl |

| 4 | fa | ēt |

| 5 | lima ~ nima | lim |

| 6 | ondo | lijia, lesu |

| 7 | fiti ~ piji | leôru |

| 8 | walo | lētēl |

| 9 | suan | liapat |

| 10 | tendu | sungul |

Like many languages spoken in the region of Melanesia, resources surrounding the Sa language are understandably scarce. While the first recorded mention of the Sa language may be dated back to 1899, linguistic, anthropological, and cultural studies of Sa and its speaking populations were not really published or conducted until the mid 20th century, and research was paused under a moratorium imposed during the early years of Vanuatu’s independence (and later in 2013 to 2014). Even so, many of these were also grouped together with other people groups in Pentecost Island, and as such, finding publications covering more specific areas of the Sa language has proved difficult. Nevertheless, I have mentioned some of the more accessible ones down in the Further Reading section, which have also served as resources I have consulted in the writing of this introduction.

Further reading

Clark, R. (1985) ‘Languages of North and Central Vanuatu: Groups, chains, clusters and waves’, Austronesian linguistics at the 15th Pacific Science Congress, Canberra, pp. 199-236.

Elliot, G. R. (1976) ‘A description of Sa, a New Hebridean language’, unpublished MA thesis, Macquarie University, Sydney.

Garde, M. (2015) ‘Numerals in Sa’, In: (ed. François, A., Lacrampe, S., Franijeh, M., Schnell, S.) The Languages of Vanuatu: Unity and Diversity, Studies in the Languages of Island Melanesia, Canberra, pp. 117-136.

Recordings of Sa on the Global Recordings Network: https://globalrecordings.net/en/language/sax