In the grand timeline of human history, writing is actually a fairly recent invention, with its first attestations arising just 5000 to 6000 years ago. Of course, writing systems have sprung up over time in various civilisations, from the Chinese oracle bone script to the Maya hieroglyphs, from the Egyptian hieroglyphs to the Aegean writing systems found in present-day Greece. Today, however, we will take a look into the earliest known writing system that emerged, and mention the elephant in the room of writing systems of antiquity.

Cuneiform derives from the Latin word cuneus, meaning wedge. Predominantly etched into clay tablets, this writing system has gone through many adaptations and modifications in the 3000 years this writing system has been thought to be used. Cuneiform was traditionally written using styluses fashioned from reeds, though there are some styluses made from other materials such as bone. First arising from Sumer around 5000 to 6000 years ago, one of the earliest known civilisations, this writing system would be used for the Sumerian language, and several others from Hittite and Akkadian, to even Old Persian. It stretched across multiple language families, such as the Semitic languages which include Akkadian and Ugaritic, and Indo-European languages which include Old Persian and Hittite, necessitating modifications and adaptations to suit these respective languages. As a result, the various cuneiform types would also encompass logographic systems, syllabaries, alphabets, and abjads alike, depending on the language that used them.

To understand how cuneiform started, we have to take a look at the history of writing in Mesopotamia first. There was once a token-based system fashioned out of clay to represent various physical objects such as goods and livestock. Dating as far back as 10 000 – 11 000 years ago, these tokens have been proposed as being the progenitors of what would become cuneiform. Over time, people started making symbols in the clay as opposed to crafting these clay tokens, and a numeral system would also develop represent multiple counts of the same glyph, indicating some plurality. This proto-writing would have largely developed as a pictographic system, where one object would have been represented by one glyph.

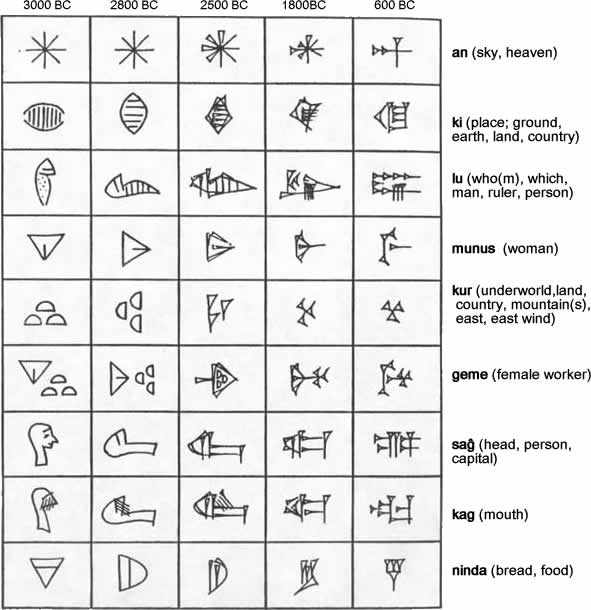

As cuneiform developed, pictograms would be rotated, and abstracted, before ultimately appearing as a system of wedge-based inscriptions in clay tablets. The type of writing implement would change as well, as styluses making inscriptions in the clay would change from pointed ones which made more linear strokes, to the angular ones which made wedge-like strokes. As the first tablets recovered were of a pictographic system, we cannot really ascertain which language was represented, though many would assume that the Sumerian language was written in these tablets.

However, since around the 29th century BC (yes, around 2900 BCE), tablets would start to show some characteristics of syllabaries, reflecting the use of individual characters to represent sounds in a language. Clay tablets dating back to this time have been agreed to be representing the Sumerian language. Over time, there would be fewer and fewer unique signs in use, as the pictographic system died out in favour of the syllabary system, though some pictograms were used for some distinctions (like deities, nobility, and upperclassmen, or just to avoid ambiguity). Similar-sounding words would start to be written using the same character, and a more syllabic Sumerian cuneiform would have used several hundred characters (down from at least a thousand symbols in older Sumerian texts), though spelling would have differed at least in some part between speaking and writing communities.

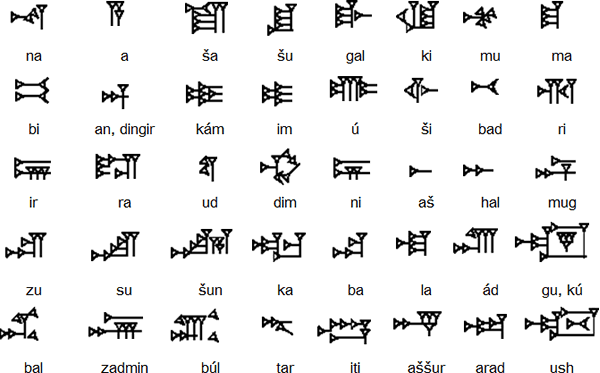

The first major spread of Sumerian cuneiform to other languages was with the Akkadian language in the 24th century BCE. A Semitic language, Akkadian would adapt the Sumerian cuneiform system to reflect Akkadian sounds, although some signs or sign combinations would be used for some objects, referred to as Sumerograms or a type of heterogram. As Akkadian and Sumerian sounds and phonotactics differ greatly, the characters representing Sumerian sounds would not be really intuitive to the Akkadian speaker. As such, these characters would be modified to represent Akkadian sounds and syllables not present in Sumerian. Other characters also included some syllabic and some logographic meaning. Additionally, these characters would be further abstracted, yielding five identifiable basic stroke patterns in Akkadian cuneiform, the horizontal, vertical, upward diagonal, downward diagonal, and the hook, or Winkelhaken stroke. In a way, this could be paralleled with the adoption of Chinese characters in Japanese centuries ago, where some Chinese characters were used to represented Japanese syllables, and others were used as logograms.

The next major adoption of cuneiform would be by the Hittite language, an Indo-European language, in the second millennium BCE. Hittite cuneiform is an adaptation of a type of Akkadian cuneiform called Assyrian cuneiform. Here, around 600 signs have been identified, with half of them representing syllables, from V, CV, VC to even CVC, and the others of Sumerian and Akkadian origin that represent ideograms, semantic categories, or other kinds of words. Other syllabaries and writing systems would develop, such as in the Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian cuneiform, and Hurrian and Urartian cuneiform. These systems would have varying degrees of abstraction in their characters, as well as varying emphases on syllabograms or logograms and ideograms in their respective orthographies. Neo-Assyrian cuneiform, for example, tended to have more angular characters and a higher degree of abstraction, while Hurrian cuneiform tended to focus more heavily on syllabograms.

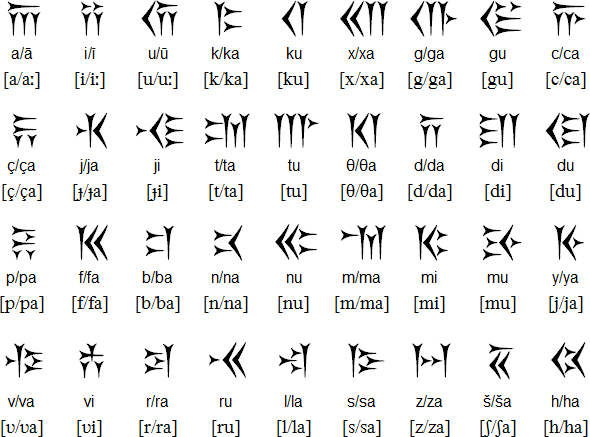

One of the most significant types of cuneiform that developed independently of the cuneiform systems we mentioned earlier is Old Persian cuneiform. With 36 characters encoding phonetic qualities and 8 identified logograms, Old Persian cuneiform has substantially fewer signs compared to other aforementioned cuneiform systems. This system is identified to be a semi-syllabary, where some characters represented CV or V syllables, while others appear to represent the consonant value only. There were also fewer strokes per character in Old Persian cuneiform, with three different basic stroke patterns, horizontal, vertical, and the hook or the Winkelhaken stroke.

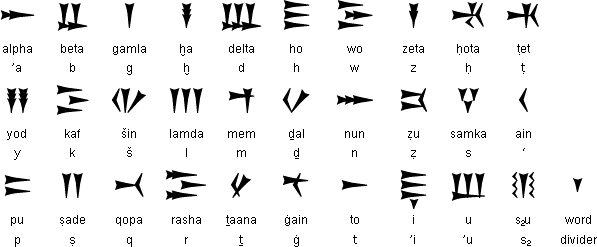

Perhaps one of the later adoptions of cuneiform is that of the Ugaritic language. Classified as a Semitic language, Ugaritic would adopt cuneiform towards the 15th century BCE, before falling out of use in the 12th century BCE during the Bronze Age collapse. Like Old Persian cuneiform, Ugaritic cuneiform developed independently of the other cuneiform systems, although the basic strokes are largely similar to the other systems. This abjad (an alphabet with only consonants) would contain 30 letters, with an additional word divider as the sole punctuation mark, making it the smallest cuneiform system by character inventory.

Despite being in use for nearly 3000 years, leading to the rise of other cuneiform writing systems, this would all cease in use by the 1st to 3rd centuries. The languages that once used cuneiform either faced a decline and eventual loss (like in the Bronze Age collapse) or assimilation to other kingdoms and empires, or moved towards writing using another writing system. The implements of writing would also change, as clay tablets would fall out of use, in favour of papyrus and paper-like materials, or chiseling into stone. For instance, Old Persian would move into the Middle Persian era by the 3rd century BCE, using alphabets and abjads instead of the semi-syllabary cuneiform of antiquity, and later, the Perso-Arabic script that was used from the 7th century to this very day.

Cuneiform would have gone forgotten for centuries, and it was not until the 17th century when the first cuneiform tablets would be unearthed, copied, and published. Decipherment efforts would soon follow, with the first attempts recorded as far back as the early 19th century. The first cuneiform to be deciphered was that of Old Persian, which was revealed to be a semi-syllabary in the 1830s. Since then, thousands of clay tablets would be unearthed, each telling a different story, or documentation of religion, bureaucracy, and even the first known dictionaries. Decipherment techniques would also develop and mature, with advanced computational methods such as neural networks being used to decipher and translate written Akkadian, amongst other kinds of languages written in cuneiform. This would lead up to the oldest known customer complaint, written in the Akkadian language as a complaint about poor-quality copper and mistreatment of a servant, with memes that would develop as a result of this very discovery. Today, cuneiform remains a topic of interest by historians, linguists, archaeologists, and enthusiasts in these disciplines.

Featured image: Complaint Tablet to Ea-nāṣir, in Akkadian cuneiform, dated to around 1750 BC in Ur, currently in the British Museum in London.