The Japanese language is known to employ three different writing systems in recording the language, with the hiragana and katakana syllabaries, as well as kanji. While there are 46 basic characters for hiragana and katakana, these numbers are greatly dwarfed by the number of kanji currently in frequent use, such as the 2136 kanji taught in schools, with a further few hundred more that are commonly used in writing Japanese. However, the actual precise number of kanji that has ever existed is much less clear, though estimates put it at well over 50,000.

But what about those that have been digitised? Japan has its own set of industrial standards called the JIS or Japanese Industrial Standard, which encompasses the standard set for use in the exchange of information in data communication. First created in 1978, this served to drive the digitisation of the Japanese language, and how Japanese characters are stored, displayed, and sent through data communication and text processing systems. Today, it uses the JIS X 0213, which built on a preceding standard called the JIS X 0208. While the JIS X 0208 included 6879 characters, of which 6355 were kanji, the JIS X 0213 has added around 3600 more kanji characters since its publication in 2000.

However, amongst the thousands of kanji that have been added to the Japanese Standard and other international standards for digitalisation of writing systems, there are some that seem weird. Not weird in the sense that they appear unusual, but more rather, weird in that no one knows what these actually mean, or if it is actually used at all.

Today, there are 12 of these kanji among the 6355 characters included in the JIS X 0208 set that carry an unknown meaning and an unknown usage. Collectively known as ‘ghost characters’ or 幽霊文字 (yūrei moji), these characters are 墸 壥 妛 挧 暃 椦 槞 蟐 袮 閠 駲 彁. Each of them have their own supposed pronunciation, just that they do not seem to have a clear origin, nor meaning. Some of them are typos, while others remain unclear.

But how were these characters even added in the first place?

In the 1970s, when Ministry of Trade and Industry were putting together this standard, there were four main sources that were consulted. This encompassed characters that are found in family names, given names, and place names as well. Namely, these sources were the Kanji Table for Standard Codes (Draft), National Land Administrative Districts Directory, Nippon Seimei’s family name table, and Basic Kanji for Administrative Information Processing.

It was only after the implementation of the standard that people realised that some of these characters do not really carry known meanings and known contexts in which they are used. Upon further investigation, many of these characters also carried no mentions in dictionaries that cover more ancient Chinese characters, such as the Chinese Kangxi Dictionary 康熙字典 and the Japanese Dai Kan-Wa Jiten 大漢和辞典.

Despite this, in 1997, it was determined that many of these characters once referred to as ‘ghost characters’ were actually used in place names. Even so, there were 12 characters that remained under this ‘ghost character’ classification. Some were typos, while some could be somehow found in dictionaries like the Kangxi Dictionary or the Dai Kan-Wa Jiten. And this status remains to this very day.

Being a native speaker of Mandarin Chinese, and a conversational user of Japanese, I thought that some of these ghost characters appeared rather familiar, although I had to confirm that these are indeed erroneous forms of already existent characters that are actually in use. And so, I would like to raise a couple of examples I thought appeared strangely similar to what I am familiar with.

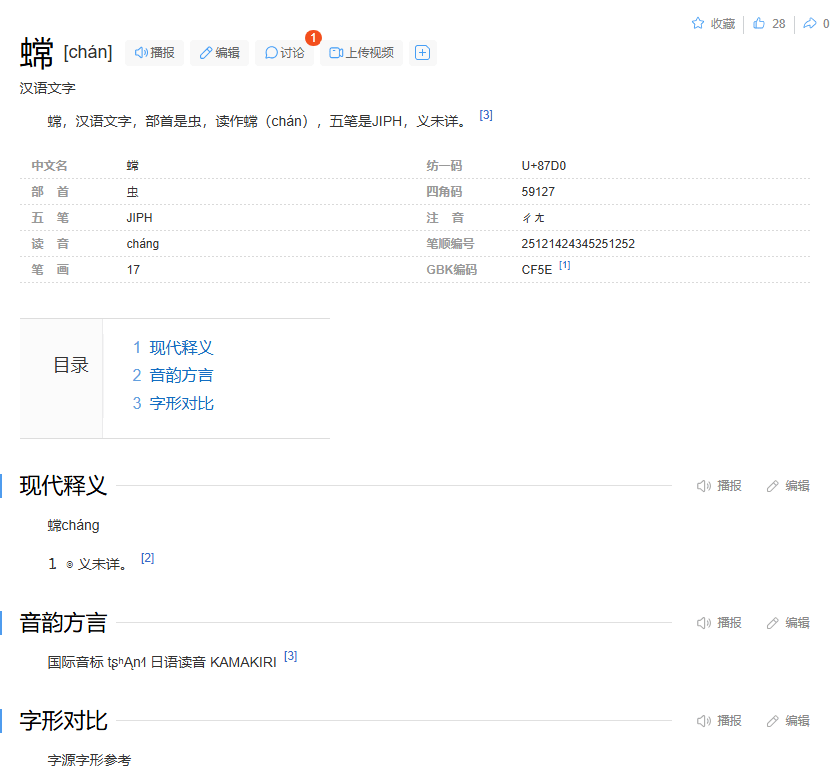

The first character I want to mention is 蟐 (ZH chán, cháng, JA On tō, Kun kamakiri). For some reason, I thought that this would be pronounced the same as in Chang’e or 嫦娥 (in Japanese, じょうが、こうが) given the similarity in characters, but there is a difference in radicals used.

Interestingly, while the Mandarin Chinese character entry does not mention a known meaning for the character, the Japanese counterpart suggested that 蟐 actually referred to some kind of toad, with the Kanji Jiten Online suggesting akagaeru. This prompted me to look even further, and I found that this could have referred to a specific species of frog called the Japanese brown frog or Rana japonica, with the common name being ニホンアカガエル (nihon akagaeru), and the kanji being 日本赤蛙 instead, perhaps just a similarity by common name. It turns out that the main source suggesting this character was from the 1803 manuscript of the Shinsen Jikyō, 新撰字鏡.

It was also suggested that 蟐 is an erroneous form of the character 蟷 (ZH dāng, JA On tō), as in the Japanese compound 蟷螂 (kamakiri), which refers to a mantis. Its Mandarin Chinese counterpart is 螳螂 (táng láng). I think it was the similar semantic meanings and pronunciations that formed my impression that 蟐 is an actual character that I should be familiar with, but is actually not, and I do not really have to worry about it.

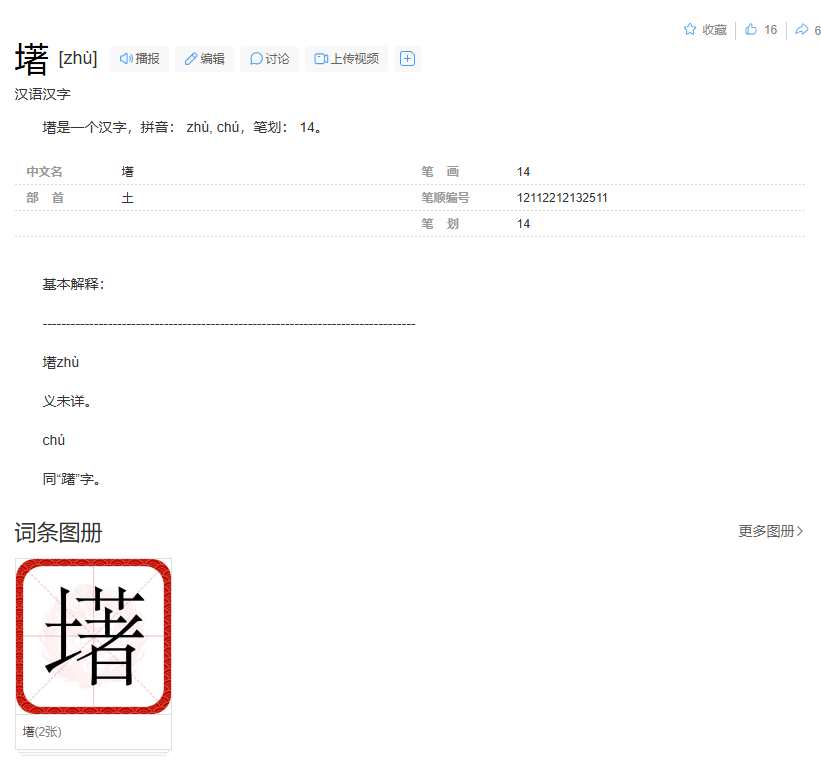

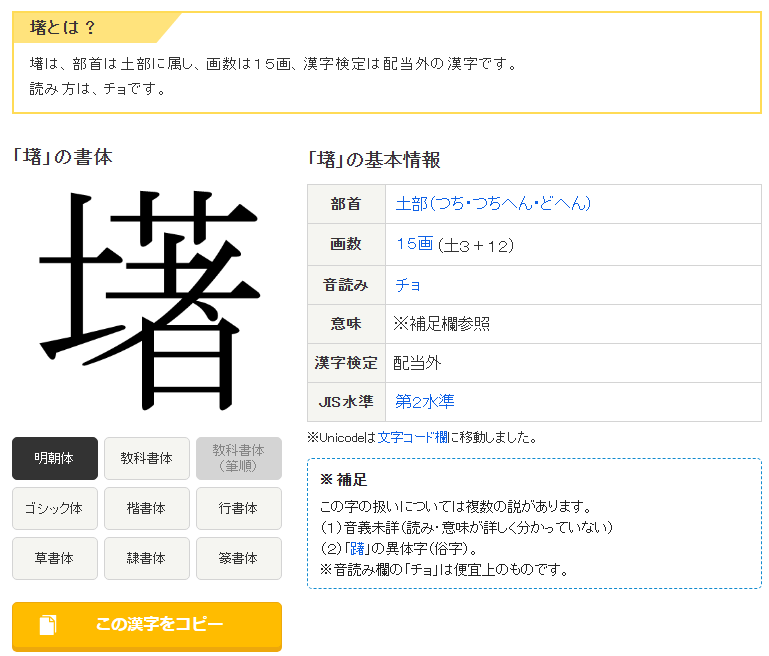

The second character I want to mention is 墸 (ZH zhù, JA On cho), given the code 52-55 in the JIS X 0208. The Mandarin Chinese counterpart, which lacks 1 stroke present in the Japanese one, mentioned that there is an unknown meaning. Other entries may suggest that the character means ‘to hesitate’, but upon further digging, the actual character conferring this meaning is 躇. Some dictionaries like the Japanese one below mentioned that 墸 is an erroneous or a variant form of the more commonly used character 躇. Another related character, at least in structure, is the character 堵 (ZH dǔ, JA On to, Kun kaki). This one, unlike the, actually means ‘wall’ or ‘to block’. Perhaps the blend of similarly structured characters and pronunciations is why I thought that 墸 looked familiar.

Characters like 槞 could be argued to be a variant of another character like 櫳. For this case, when you drop the radical on the left of the character, you would get the character 龍, and its variant 竜, which means ‘dragon’, ryuu (on’yomi) or tatsu (kun’yomi). Meanwhile, 妛 was suggested to enter the standard because of how the character was formed. The National Land Administrative Districts Index, the main source of this character, wanted to render the character 𡚴, which can be formed by stacking parts of its constituent strokes in a top-bottom pattern, with 山 on the top and 女 on the bottom. However, when these were combined, there was a mark that rendered as a line between the two parts. This would have been interpreted as a separated horizontal stroke, and hence the character 妛 was ‘born’.

In a way, this resembles the ghost words in dictionaries, notably like the word ‘dord‘, which are words with almost no practical use, and no previously known meanings prior to their addition to dictionaries. After all, in Japanese, these characters have been argued to be mostly typological errors of existing characters in the language, and that these erroneous characters essentially carry no or an unknown meaning. Thus, their main ‘practical use’ could be argued as being typos or errors, instead of conveying actual meaning in a given text or display.

The thing is, these characters have already been added to Unicode, a text encoding standard that aims to support text written in displayed in every single writing system in the world that are (and can be) digitised. Per Unicode’s Character Encoding Stability Policies, characters, even if they are erroneously added, may not be removed, reassigned nor reallocated. However, what they can do is to deprecate the character, which is essentially discouraging the use of these characters because they are “obsolete” or in this case, likely erroneously added. And so, these ‘ghost characters’ persisted in the Unicode, primarily serving as topics for obscure trivia knowledge and language enthusiasts like this very essay, where they are still rendered as text.