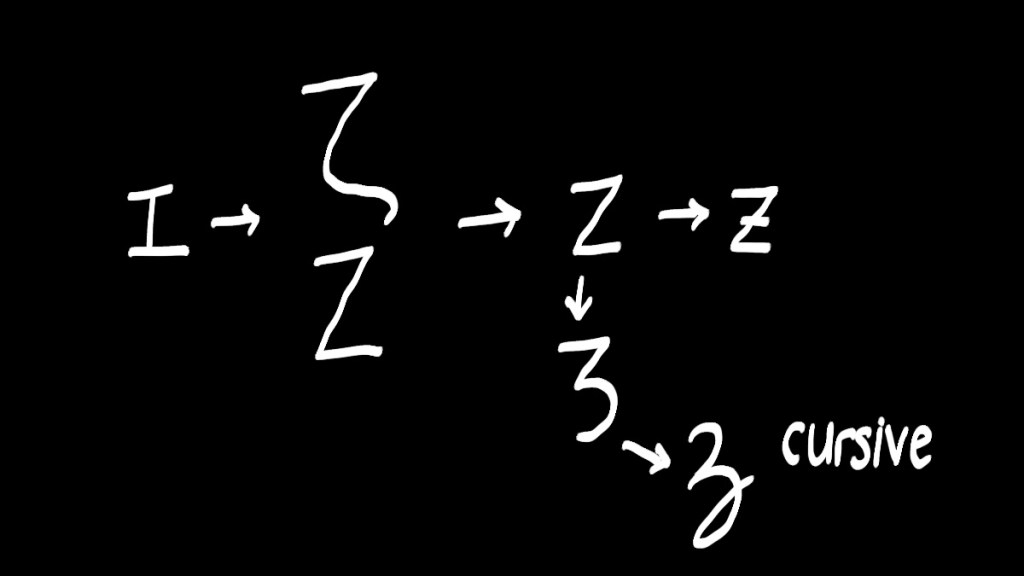

I want to start today’s dive with a little poll. I want to ask, how do you write the letter ‘z’?

Observing how people write this letter, I cannot help but to dig into why three such forms predominantly exist in our handwriting. Personally, I write my z’s like 𝔷, while many others I know write them like z. But is this a stylistic choice, or is the reason for these variants much more than what meets the eye? Join me, as we enter the history of the letter ‘z’, and how we got our predominant forms of the letter ‘z’. We will not really touch on the sounds the letter ‘z’ represents across languages, although that might be worth looking into at some point later on.

The letter ‘z’ as we know it kind of dates back to the time of the hieroglyphs, although the first mention in a phonetic alphabet was as the letter zayn in the Phoenician abjad. It translates to some sort of bladed implement, some sources say it is a sword, while others imply another type of weapon. It pretty much retains its name all the way into modern Semitic languages like Arabic and Hebrew as zayn or zāy, and zayīn respectively.

This led to the letter zeta in the Greek alphabet. It sort of did away with the original zayn name in favour of following the pattern used to name Greek letters such as eta, theta, and beta. While the lowercase zeta is derived from the uppercase counterpart, how or why it is written as such is unclear to me.

But it is this Greek origin where we would find the letter Z we use today, including the name of the letter, ‘zed’, in many anglophone countries except the United States (who use ‘zee’). That is, if we borrow the uppercase zeta.

Perhaps if you do not write ‘z’ as, well, ‘z’, you might write it with a stroke in the middle of the letter. While to most, the preference to write ‘ƶ’ rather than ‘z’ is a stylistic choice, there are its own upsides. For one, it reduces the likelihood of the letter being mixed up with the number ‘2’. This is especially true in mathematics and other quantitative fields. However, there are also other cases where the ‘ƶ’ is written as an allograph of other letters in other languages, such as the Latin alphabet of the Karachy-Balkar language found in southwestern Russia.

Now, we arrive at the form that looks like a 3, the ‘𝔷’ variant, also known as a tailed ‘z’ or ‘ezh’. You would find this in some texts with cursive writing on them, and you might also find them as block letters. Its history dates back to blackletter and Gothic writing, as far back as the 12th century. Other sources point towards the cursive Latin ‘z’. While we do not know precisely why this variant has a tail, there is a hypothesis that this tail was to aid fluid motion in writing cursive. But we do not quite know for sure how true that is. Some sources also state that in some orthographies, the tailed ‘z’ is simply a glyph variant of the letter ‘z’, and is not an ‘ezh’.

But confusingly enough, the tailed ‘z’ shares striking similarities with a forgotten letter of the English alphabet — the ‘yogh’, or ‘Ȝ’. This letter has a separate origin from the tailed ‘z’, deriving from a variant of the letter ‘g’ called the Insular ‘g’, ‘Ᵹ’. Over time, the tailed ‘z’ and ‘yogh’ became indistinguishable in English and Scots writing, with some Scots words incorporating the letter ‘z’ instead of the ‘yogh’ if printers lacked the latter. A common example is the family name Mackenzie, which was once written MacKenȝie.

Another letter that looks quite similar is the Cyrillic letter ‘ze‘, or З, з. It derives from the Greek zeta, much like how the Latin alphabet derives its Z from the same letter. But how it is incorporated into the Cyrillic alphabet takes a slightly different method. It was first seen as a Z, but with a tail on the bottom, as ꙁ. This letter was originally called землꙗ, zemlja, translating as ‘earth’. It is not known how the current Cyrillic form evolves, but Medieval Slavonic manuscripts started showing the letter з as a variant of zemlja. For some time, the two variants were used almost interchangeably, although in Ukrainian texts, з would be found in the initial position, with ꙁ written at any other position.

This all changed in the 17th century, when reforms were made that abandoned the use of ꙁ, in favour of the з variant. Looking at cursive Cyrillic version of the letter з, we see how identical it looks to the cursive Latin counterpart. This might also have been done to reduce confusion with the number 3, just like how the ‘z’ with stroke reduces confusion with the number 2.

As it stands, the choice of variant when writing the letter ‘z’ in the English alphabet seems to be a stylistic choice, such as cursive writing, or the need to reduce ambiguity with the number 2. Unlike other writing systems such as Japanese, where we find variants like hentaigana, we do not really see a gradual evolution of variants in manuscripts. Some have suggested the maintenance of a fluid motion and beauty in cursive writing for the tailed ‘z’ variant, but that leaves much to speculation. I hope you have learned a thing or two about the history of one of the letters we use every day, and some associated similarities with other letters, even in other writing systems.