In the German-speaking countries, there are several greetings one would tend to encounter depending on where one is. Sure there is the ubiquitous Hallo, but there are also regional ones from Grüezi in Switzerland and Servus in Bavaria and Austria, to Moin the further up north you go in Germany.

One of the languages in which you would find the very last greeting is Low German, also referred to as Low Saxon. Moin, in fact, may trace its roots to Middle Low German moi(e), meaning ‘good’ or ‘beautiful’, according to the Duden dictionary. Spoken by a couple million people to a ‘very well’ extent, and several million more to a ‘well’ extent, Low German is best described as a collection of language varieties that are mainly spoken in northern Germany, parts of the Netherlands, southern Denmark (in Jutland), and much less so in Poland. Classifying these varieties have proven to be a messy affair, as there has been extensive debates on whether Low German is a separate language or a group of dialects of the German language.

Before moving on, we have to cover some terminology. The ‘Low’ in Low German does not refer to the demographic of people who speak it, and bears no relation to the latitude in which it is most spoken. Instead, this refers to the low altitude where Low German is predominantly spoken, which mostly consists of plains and low-lying coastal areas, which stands in contrast to the relatively mountainous areas (the Alps) where High German is spoken. This is also the explanation for the counterparts in German (nieder vs hoch).

Unlike the High German varieties we have covered in previous introductions, the Low German varieties have not undergone this phenomenon called the High German consonant shift. This pattern of sound changes is what gives us the German Schiff, in contrast to the Dutch schip (ship). This largely pertains to the changes in stop consonants /k/, /t/, and /p/, as well as the devoicing of the /d/ sound. High German varieties have undergone varying extents of this consonant shift, with those in southern Germany and Switzerland having more sound changes. We could illustrate several examples below, using East Frisian Low German as an example for Low German, Standard German, and Dutch for comparisons.

/k/ to /k͡x/ (word-initial, geminated), /x/ (word-medial, word-final)

| English | East Frisian Low German | Standard German | Dutch |

| king | König | König | koning |

| I | ik | ich | ik |

| to do | maken | machen | maken |

/t/ to /t͡s/ (word-initial, geminated), /s/ (word-medial, word-final)

| English | East Frisian Low German | Standard German | Dutch |

| two | twee | zwei | twee |

| water | Water | Wasser | water |

| out | ut | aus | uit |

/p/ to /p͡f/ (word-initial, geminated), /f/ (word-medial, word-final)

| English | East Frisian Low German | Standard German | Dutch |

| pan | Panne | Pfanne | pan |

| to sleep | slapen | schlafen | slapen |

| ship | Schipp | Schiff | schip |

/d/ to /t/

| English | East Frisian Low German | Standard German | Dutch |

| death | Dood | Tod | dood |

| to bid | beden | bieten | bieden |

| bed | Bedd | Bett | bed |

There is no standard form of Low German unlike High German (as Standard German today), and so sounds, words, and expressions will differ depending on where in the Low German-speaking regions one finds themself in. Nevertheless, there are some grammar patterns we can see amongst the Low German varieties.

Like some High German varieties in Bavaria, Low German varieties generally lack the genitive case. Instead, possession is formed today using dative or oblique constructions, or using the preposition von. However, in some expressions, you would hear relics of the genitive case that used to occur in Low German, often in expressions termed as “frozen genitive expressions”, such as adverbs of time eens Dags (one day). Here, one would see the article des, or its shortened form ‘s (like in Dutch).

In addition to the lack of the genitive case, Low German varieties may merge the functions of the accusative and dative cases into a single oblique case. Exceptions do occur, such as the Westphalian varieties of Low German. Amongst these, the only full article for this oblique case is den (which may also be written denn or dän), used for the masculine grammatical gender (de Mann – den Mann, de Fru – de Fru, dat Kind – dat Kind).

Another feature is how the ge- prefix occurs in Low German, a feature which loss we have talked about for the case of the development of the English language. How this prefix occurs depends on the region, as the ge- prefix is used in Low Prussian, occurs as je- in Mittelmärkisch, and e- in the Ostfälisch dialect group. However, you will not find this prefix in East Frisian, Northern Low Saxon and Mecklenburgisch groups. For example, the participle ‘slept’, would translate to geschlafen in Standard German, eslapen in Ostfälisch, and slapen in Northern Low Saxon.

As a recognised minority language in Germany and the Netherlands, the Low German varieties are rather extensively documented in general, with a rather rich availability of literature, theater, and other cultural materials in Low German. However, the vitality of individual dialects varies from variety to variety. While East Frisian Low German has a very active speaking community, Low Prussian is no longer transmitted to the younger generation, following the expulsion of Germans in 1945 from what is now Poland. The minority who remained in Poland have moved to using Standard German instead of Low Prussian as well.

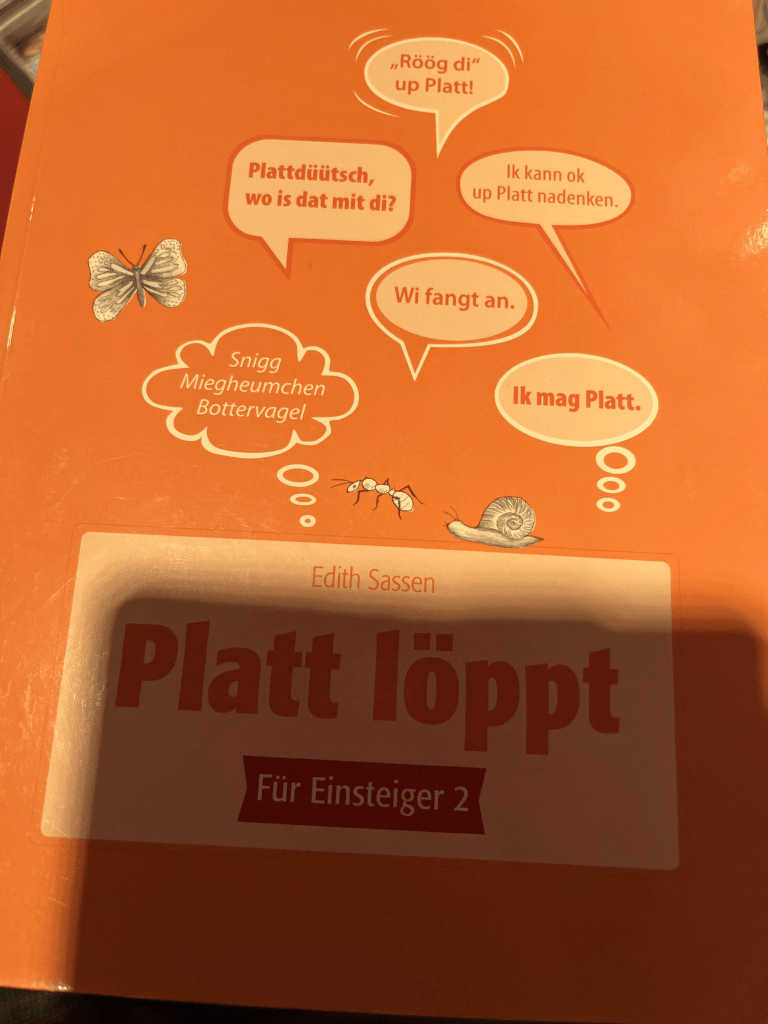

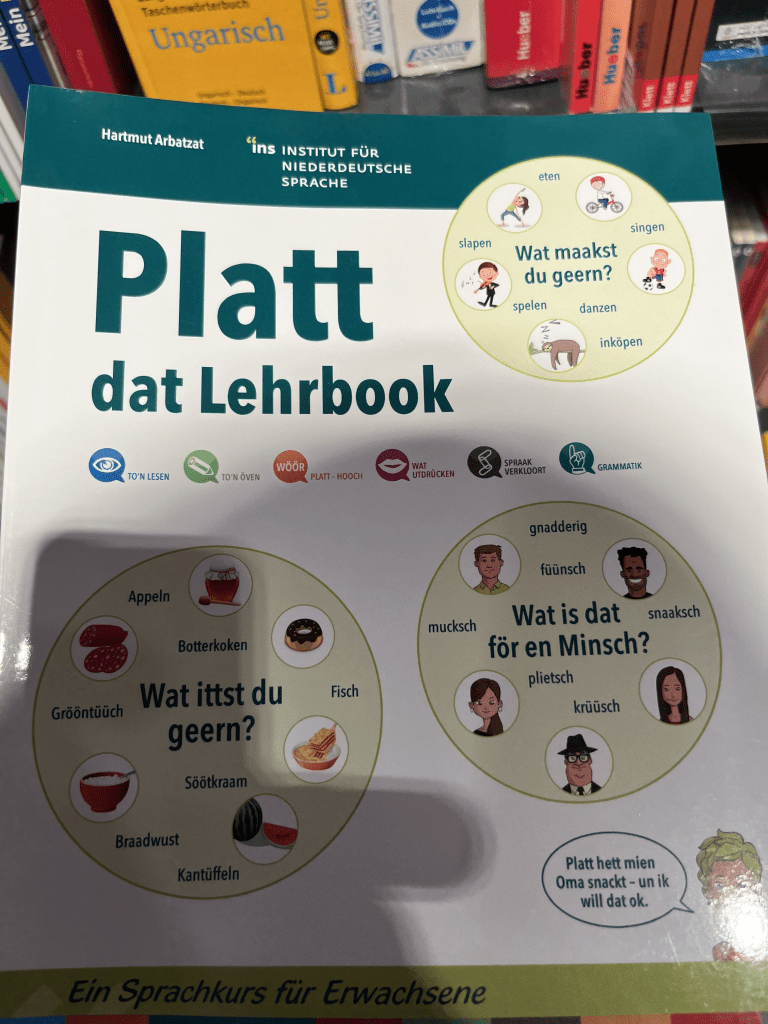

Plattschapp & Plaggenhauer is an example of a publisher and bookshop for Low German literature. Additionally, there are also coursebooks for Low German, despite the lack of a standard form of Low German. One example is the coursebook by the Institut für Niederdeutsche Sprache, an institution based in Bremen, and Platt löppt published by Isensee Florian GmbH in Oldenburg. There is also the book published by Duden in the image at the start of this introduction too. In the materials of varieties in Germany at least, these tend to follow German orthography rules, particularly the one developed by Johannes Sass (or Saß), who has made significant contributions to the documentation and research on Low German. These resources have helped formed this introduction to the Low German varieties, and are in German. I found these books in bookshops in Berlin, so perhaps give bookshops a go the next time you visit the northern regions of Germany.

Next time, we will look at one of this very variety of Low German, one that is spoken in East Frisia, or East Friesland.