Previously, we have looked at the Hachijō language, a Japonic language spoken in the Izu islands and the Daitō islands in the south of Japan. Today, we will take a look at Okinawa Prefecture, in which we can find the Ryukyuan languages. The Ryukyuan languages form a distinct branch in the Japonic language family, making it distinct from the substantially more dominant language in the family, Japanese. Amongst the Ryukyuan languages, many of us would be familiar with Okinawan, or ウチナーグチ (Uchinaaguchi), which is predominantly spoken in the island of Okinawa and its surrounding islands.

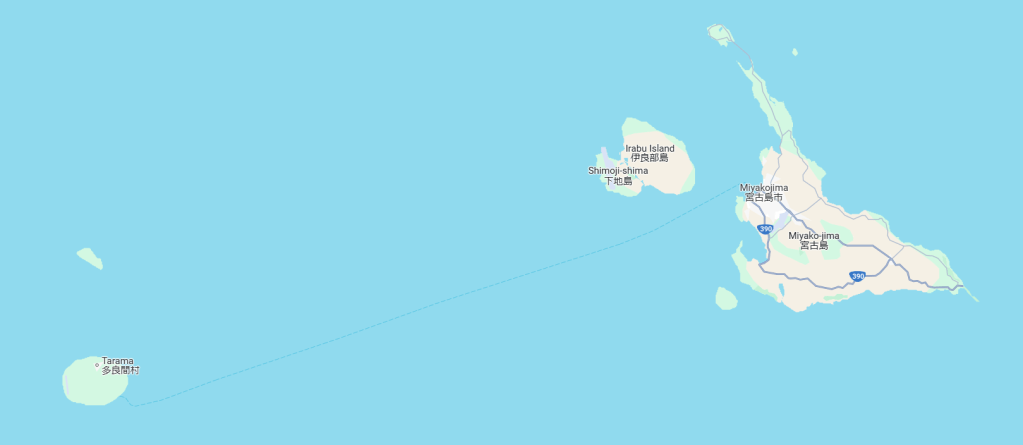

Miyakoan (ISO 639-3 mvi, Glottolog miya1259), or 宮古口/ミャークフツ (Myākufutsu), is one such example of a Ryukyuan language. Spoken mainly in the Miyako island group in Okinawa’s southwestern parts, namely, the islands of Irabu, Tarama, Ikema, Ogami, Yurima, and Miyako, we do not really know precisely how many native speakers there are, though Ethnologue suggests that most native speakers today are older adults. Census estimation in 2013 gave us an estimate of 53,015 residents of the Miyako islands, and so, it is reasonable to assume that the actual speaking population of Miyakoan is substantially smaller.

Transmission of the Miyakoan language to the younger generations seem to be limited, as younger speakers are more likely to be native speakers of Japanese instead of Miyakoan. Consequently, we should expect the language to be endangered to some extent, and that its status is in considerable trouble.

The Miyakoan language is better described as a ‘dialect cluster’, wherein the sounds and words used in each constituent dialect can vary, some even substantially. Tarama, for example, is a relatively divergent variety of Miyakoan, with so low mutual intelligibility it has been argued to be a distinct language from Miyakoan. The Glottolog language catalogue has a distinct entry for Tarama, tara1319, but it is not given its own ISO 639-3 code.

While Miyakoan displays most of the features of a Japonic language, such as its pitch-accent system (in some dialects), agglutinative nature, and its subject-object-verb canonical word order, Miyakoan does display some unusual features such as in its phonology and phonotactics, and how it expresses focus and interrogative clauses. The presence and absence of some of these features largely differs between the dialects, varieties, and sub-varieties of the Miyako language, but nonetheless, we will take a look at some of these salient features.

Amongst Miyakoan phonotactics, there is this unusual feature where fricatives like /f/ and /s/ can be used in the coda of a syllable, that is, the end of the syllable. In Japanese, this coda is exclusively /N/, the uvular nasal consonant, and this consonant cannot occupy other roles in the syllable. In Miyakoan, however, the nasal consonants /m/, /n/, and /ŋ/, the fricative consonants /f/, /s/, /v/, and /z/, and the retroflex lateral flap consonant /ɭ/ may function as syllable coda, with the exact set of consonants differing by dialect. This makes words like pail (to grow, Tarama) and iv (heavy, Hirara Miyakoan) possible.

These consonants may also be lengthened in some dialects, and some of them may also take up the role of the nucleus, the part of the syllable that is otherwise occupied by a vowel. This mainly applies to nuclei that follow the plosive onset, like /k/, /t/, and /p/. The consonants that follow these stops are mainly restricted to the set /f/, /s/, /z/, and /ɭ/, making apparently consonant-only words possible in Miyakoan, something that is rarely heard of in Japonic languages. Examples include psks (to pull, Hirara Miyakoan), m: (fish meat, Irabu Miyakoan), and ksks (to listen, Hirara Miyakoan).

How this may have arisen is through the so-called “fricativizing” of the apical vowel. So, what do these even mean? The apical vowel refers to the vowel that is articulated similar to the vowel [ɨ], a high central unrounded vowel, but it is an entirely distinct vowel that phoneticians have assigned the character [ɿ], a non-standard symbol in the International Phonetic Alphabet which you might also find in the transcriptions of Chinese languages. What this ‘apical’ part entails is, the tip of the tongue is shifted towards the alveolar ridge in articulation while the front and body of the tongue are positioned as if the speaker is making the [i] sound. Such a vowel can occur in Miyakoan dialects like those in Irabu and Hirara.

The “fricativization” of the apical vowel alludes to the close proximity in the place of articulation of the alveolar fricative consonants and the apical vowel, leading to the syllabic /s/ and /z/ over time. /s/ would follow the voiceless plosives, while /z/ would follow the voiced plosives. Additionally, the *[ɿ] sound that occurred in some places in Miyakoan syllables in its history would also become /z/ over time.

The Miyako language shares many of its grammatical features with other Ryukyuan languages and even Japanese, such as its canonical word order, and the use of inflections to reflect grammatical mood. For example, there are inflectional markers attached to verb stems to express moods like conjecture and inference (-adi, conjecture marker, and sa:i, inference marker). Additionally, some of these markers have been determined to be cognate with Japanese mood markers, with one example being the marker (actually an adjective) used to express one’s desire, ほしい (hoshii). This is realised as puskaz and puskal in the Central Miyako and Irabu varieties respectively. Furthermore, Shimoji Michinori, a linguist who specialises in Irabu Miyakoan, has found out that Irabu Miyakoan has three different focus clitics used in sentences, which are -du for declarative sentences, -ru for yes/no questions, and -ga for open questions.

Linguists have pointed out the urgent need for documentation of Miyakoan grammar. In Shimoji’s grammar of Irabu Miyakoan, one of the varieties of the Miyakoan language spoken in Irabu-jima, the paucity of grammar sketches and grammar documentation was raised as an urgent concern, and that Shimoji’s publication on the Irabu variety was perhaps among the first and only grammar sketches and grammar publications covering the Miyakoan language.

This comes in contrast to the amount of academic interest in the phonology and phonotactics of Miyakoan, and dictionaries compiled and published by native speakers and linguists. Additionally, for some Miyakoan varieties, texts, folk songs, and other field notes have been documented for the language such as the Irabu variety, with some dating back to the 1970s. JLect has compiled a list of publications and resources covering the various languages in Japan, from Miyako to Ainu, in English and Japanese, and I would highly recommend checking them out, with some of the most relevant publications highlighted below in Further Reading.

Further Reading

Hayashi, Y., Igarashi, Y., Takubo, Y. & Kubo, T. (2008) ‘An instrumental analysis of the two tone system in Ikema Ryukyuan’, Proceedings of the Twenty-Second General Meeting of the Phonetic Society of Japan, pp. 175-180.

Jarosz, A. (2014) ‘Miyako-Ryukyuan and its contribution to linguistic diversity’, JournaLIPP, 3, pp. 39-55.

Jarosz, A. (2018) ‘Body vocabulary in “Miyako Dialect notes”‘, Dialects of the Ryukyus, 42, pp. 61-79.

Karimata, S. (2019) ‘Verb conjugation in the Miyako language: Perfective, negative, past, and continuative forms’, National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics, pp. 76-139.

Pellard, T. (2009) ‘Ogami : Éléments de description d’un parler du sud des Ryukyus‘, Docteur de l’EHESS thesis, École des hautes études en sciences sociales.

Shimoji, M. (2008) ‘A grammar of Irabu, a Southern Ryukyuan language’, PhD thesis, Australian National University.