In the very first introduction to the writing systems used in the African continent, I mentioned two indigenous systems. The first was the Ge’ez script, used to write languages such as Amharic and Tigrinya, and the second was Tifinagh, used to write the Berber languages. There was only a couple of paragraphs dedicated to each writing system, and so I thought we could talk about these writing systems in more detail.

North Africa is home to the Berber peoples, also known as the Amazigh or the Imazighen, the indigenous people groups who have lived in North Africa prior to the migration of Arabs into the Maghreb region. This encompasses present-day nations such as Morocco, Algeria, Mauritania, Tunisia, and Libya, although some Berber communities also live in Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso as well. Together, the Amazigh speak an Afro-Asiatic language known as the Berber languages, or natively known as the Amazigh languages or Tamazight (although this term could also be used to refer to a specific language such as Central Tashlhyit) . While these languages are closely related, some are not really mutually intelligible with one another. As such, linguists suggested that the Berber languages form a dialect continuum, and defining boundaries between each Berber language is difficult. You might have heard of the Tuareg languages, for example, which is a subdivision of the Berber languages spoken in Algeria, Mali, Niger, and Libya. Nevertheless, there are claims that there are over 40 distinct Amazigh languages that constitute this continuum.

While these languages are predominantly spoken, there are some written inscriptions quite literally set in stone. Furthermore, following the spread of Islam into North Africa, some Amaizgh languages started using the Arabic script to write their languages. And later in the 19th century, under European influence, the Latin alphabet has also entered use in the Amazigh languages. These writing systems generally try to unite these languages together under a common writing system. Today, three different writing systems are used to write the Amazigh languages, with certain ones being preferentially used in certain circumstances, such as bureaucracy and education. These are the Latin alphabet, the Arabic script, and Tifinagh.

Tifinagh, as we see it today, is an alphabet. It has letters representing both vowels and consonants, although there is no distinction between majuscule and miniscule, or uppercase and lowercase. But it was not always like this. Tifinagh today, known as Neo-Tifinagh, is the result of decades of development by the Berber academy to adapt Tifinagh for a specific Berber language in Northern Africa — Kabyle. This was in part, motivated by a Berber cultural movement in Morocco and Algeria during the 1960s, which opposed the spread of pan-Arabism in the region. While initially suppressed by the Moroccan government, the early 21st century brought a change, when a standardised Moroccan Amazigh was developed, and the Neo-Tifinagh alphabet was adopted. Since then, Neo-Tifinagh has gained limited use in Morocco, as some speakers preferred to use the Latin alphabet instead. Nevertheless, some Moroccan websites continue to offer Neo-Tifinagh as an option.

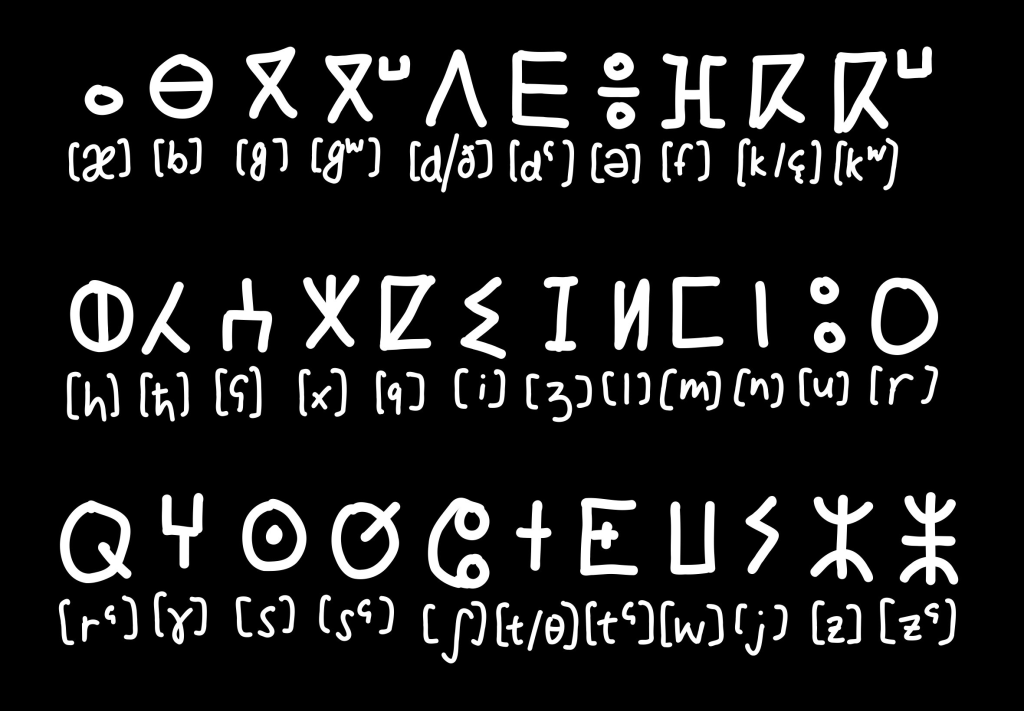

There are 33 letters in the Neo-Tifinagh alphabet, which includes 4 vowel letters. Marking glottalisation does not seem to follow a general pattern from the unmodified consonant, though it usually occurs as an addition of a stroke, or a replacement of one. Labio-velarisation is marked by the addition of ⵯ following the modified consonant.

The Unicode also lists more Neo-Tifinagh letters under the extended alphabet, or other Tifinagh letters. These likely represent the sounds that are not found in Standard Moroccan Amazigh, or other varieties of the Berber languages found in the region. There are also some letters that represent the Tuareg languages, such as the letter ⵌ, used to represent the [ʒ] sound.

But what was the original Tifinagh script then, you might ask?

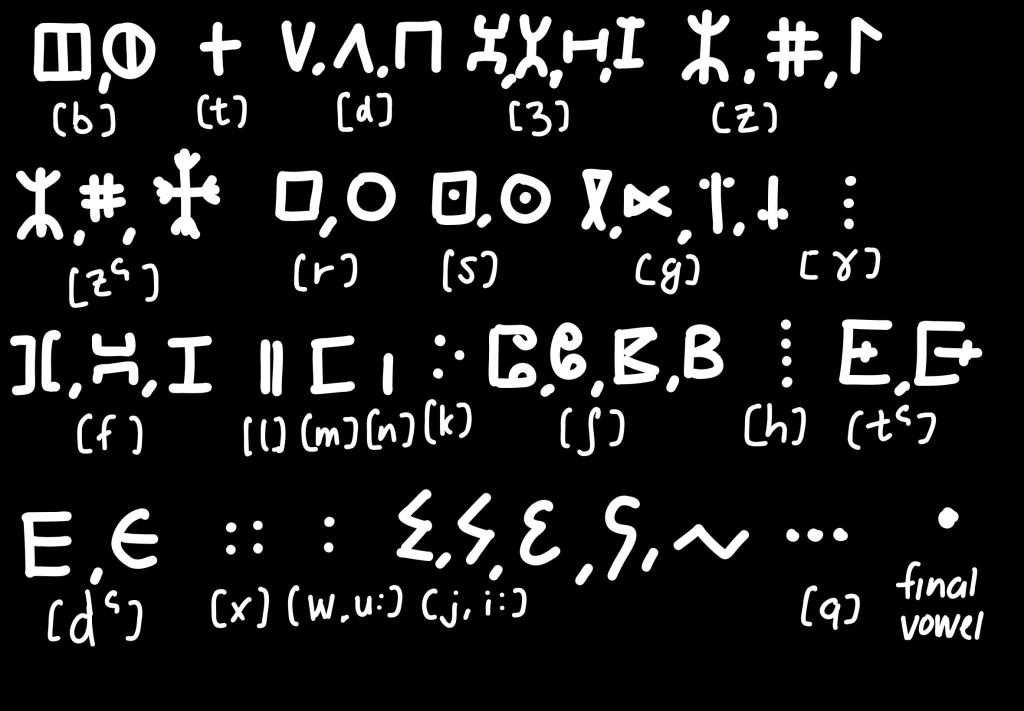

Neo-Tifinagh derived from Traditional Tifinagh, which is a collection of scripts featuring letters that only represented consonants. In other words, Traditional Tifinagh was an abjad. While there were a couple of letters which could be used to represent long vowels, vowels except the final one were not marked at all. The letter ‘t’ in particular had many combinations with other consonants, resulting in ligatures.

Writing direction also varied, with some inscriptions being written vertically, and some horizontally. This also resulted in different forms of the same letter being identified. Orthographies in Traditional Tifinagh varied by the Berber language used in the region, and perhaps even by dialect. In fact, the Tuareg languages continue to use the Traditional Tifinagh abjad with some modifications to write their languages today.

Going back further in history, we find that the Tifinagh scripts derived from the Libyco-Berber script, used to write what could be a predecessor or an ancient cousin of the Berber languages way back in the first millennium BCE. Like Traditional Tifinagh, the Libyco-Berber script consisted of only consonants, making it an abjad as well. Furthermore, dozens of different variations of the script have been identified, which would have corresponded to the dialect or Berber language spoken in the region where the inscriptions were found.

What the Libyco-Berber script developed from is still uncertain, although there are several hypotheses proposed. One example is that it developed from the Phoenician alphabet, which also did not use vowels. But according to Temehu, there were some glaring issues with that hypothesis, which included the case where the Berbers only borrowed a few letters from Phoenician, if the hypothesis was true.

Another issue was the difficulty in discerning which letters were actually borrowed from Phoenician, and which letters were actually derived from Egyptian hieroglyphs. During that period in time, it was likely that there would have been some form of convergent evolution in certain letters between different scripts, resulting in the false association between these two scripts that were descended from Egyptian hieroglyphs. It could be the case that the Berbers first developed their script based off Egyptian hieroglyphs, while incorporating several Phoenician influences into their writing system, but this is still under debate by historical linguists and researchers.

Having looked at the rather limited contemporary use of Tifinagh today, I want to look into what could be the future of the Neo-Tifinagh alphabet in Morocco and beyond, as well as the Tuareg Tifinagh abjad. Many Berber languages remain predominantly spoken to this day, with some Tifinagh usually used in short texts or inscriptions. Even Morocco’s implementation of the Neo-Tifinagh alphabet received some backlash by Berber speakers, who thought that the Latin alphabet did a fine enough job at representing their respective language. While the writing system was taught briefly in schools, today, there has not been any widespread use of the script even within education. Nevertheless, some Moroccan websites continue to offer to display their content in Neo-Tifinagh, despite its current dominance by the Latin alphabet to write the Berber languages today. Regardless of where you stand in the implementation of Neo-Tifinagh in education and beyond, I think that the Tifinagh scripts form an integral aspect to the Berber languages and cultures, and their geometrical characteristics of their letters are definitely hard to miss.

Further reading

Campbell & Moseley, The Routledge Handbook of Scripts and Alphabets, 2013