English is by no means an easy language to spell in, especially for people who are picking the language up in early education. After all, with memes going about saying mastering it is possible through thorough thought though, it is pretty evident that with all the sounds English has and the letters that are available in the alphabet, there is a many-to-many relationship between the characters that are written and the sounds that are articulated. Combined with the lack of a central body which regulates how words are spelled, spelling irregularities are abound.

Difficulties with the converse also apply, as reading aloud involves decoding what is written into what is spoken. With some words having the same spelling yet different pronunciations (tear vs tear, for instance), and a spelling system that does not always intuitively indicate how a word may be pronounced (like colonel), for learners of English, there would often be words which tend to be more easily mispronounced.

Since the time of Modern English, there have been numerous movements to try to reform English spelling to make it a bit more regular than it has been (and still is), with some focusing on the process of reading and phonics, which translates what is written to what is spoken. Today, we will take a look at one of the experiments that occurred in the 1960s, one that attempted to help make reading easier.

The Initial Teaching Alphabet or ITA was the brainchild of Sir James Pitman, who was the grandson of the inventor of Pitman shorthand, Sir Isaac Pitman. As Member of Parliament of the United Kingdom in 1959, Pitman would push for the use of the ITA for early education for children, with the intention to phase in the conventional alphabet a bit later in their education. This led to the use of the ITA in some schools in the United Kingdom, and some schools abroad as well. However, there was no academic standard set for the ITA, and neither was there an official nationwide implementation for the ITA, leading to some questionable practices when it comes to the manner in which ITA was rolled out in some schools.

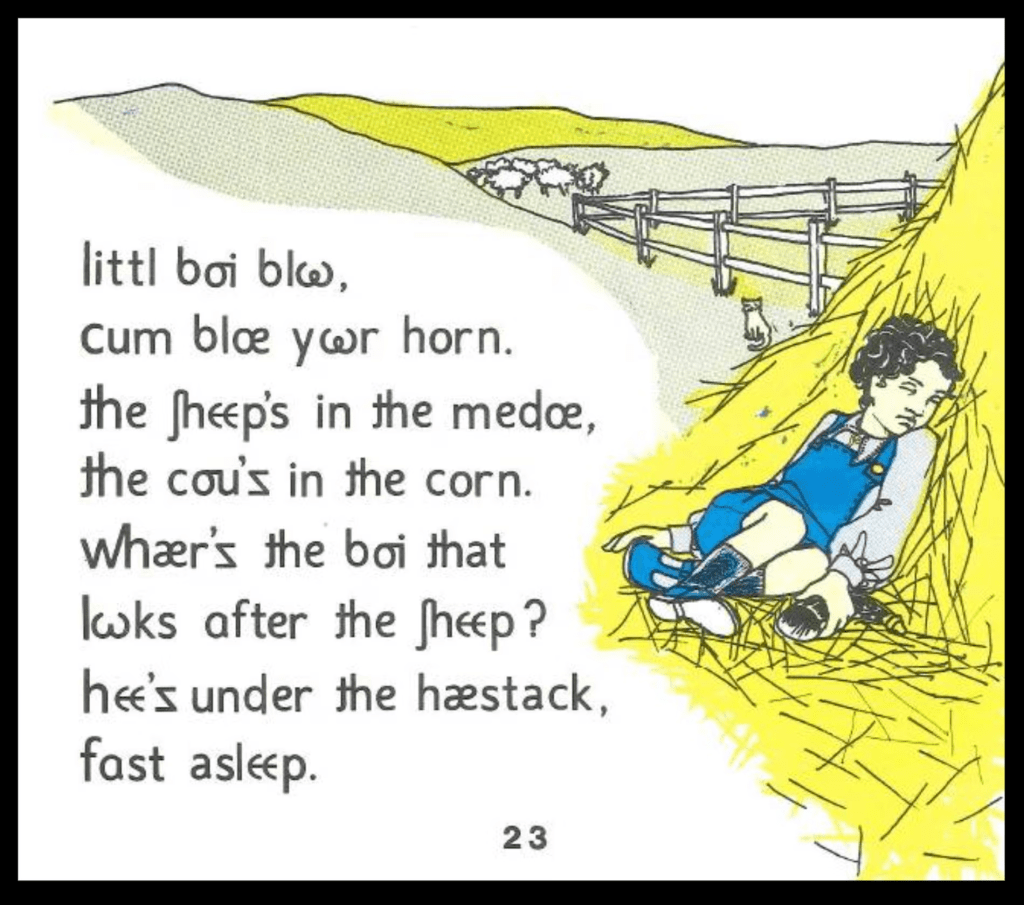

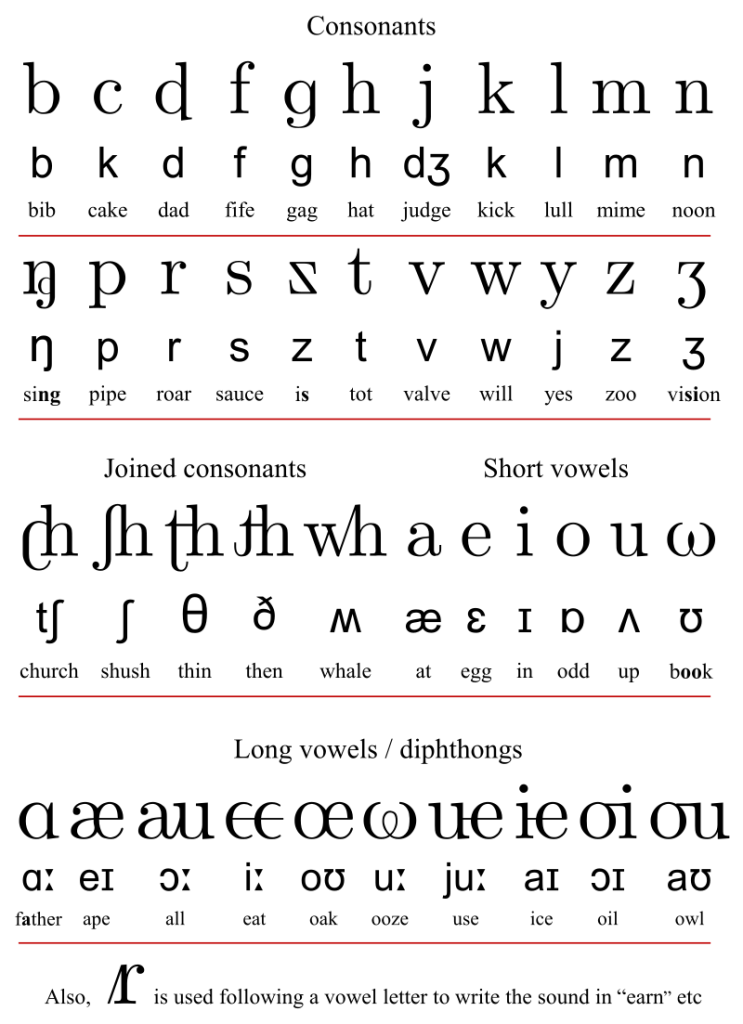

Here, Pitman attempted to create an alphabet that provides a one-to-one correspondence between the sounds of English (at least for Received Pronunciation) and the letters of the ITA. In Received Pronunciation, the variety of English accents that is generally perceived as the standard in England at least, there are 44 sounds in total. However, the initial version of the ITA included only 43 letters. One omission is the letter dedicated to the unstressed vowel [ə], which was written with the same letters as full vowels. Additionally, there were two sounds for which there were two letters representing them, which were the [k] and [z] sounds. [k] could be written as either k or c, while [z] could be written as either z or a special mirrored ‘z’ letter, which appeared in instances such as the plural forms of nouns and present tense verb conjugation for the third-person singular. Later on, an additional letter was added to represent rhotic sounds, like the ‘r’ in ‘earn’, and another one called the ‘half-hook a’ to allow for accent variation.

This alphabet would have 24 of the 26 letters used in the English alphabet, and a number of special letters. All of these were printed in lowercase. The special characters, with some exceptions (like ω), consisted of some modified form of the Latin alphabet. There were five (or six) joined consonants, with the ‘ng’ being printed as the letter similar to ŋ, but with a loop, resembling an ‘n’ joined with a ‘g’. Diphthongs and all but two long vowels would also be written as ligatures of some constituent vowels, such as oi and ue.

The implementation of the ITA in schools at the time exposed a little problem. By having ITA as a sort of introductory alphabet to younger learners of English, there is a challenge in determining when these learners are ready to progress towards the 26 letter of the alphabet we use every day. Effectively, this was teaching students two writing systems for the same language, with an additional period to sort of relearn how English is actually spelled and read by everyone. Some schoolchildren would find the transition period from ITA to the English alphabet difficult, and struggle in spelling with the 26 letters in the alphabet.

Additionally, the original implementation of the ITA was primarily based on Received Pronunciation. Speakers with other accents, such as those in Glasgow, York, or Merseyside, would deviate from this perceived standard, and would face difficulty in deciphering how a certain text printed in ITA may be read. The problem would also extend to schools outside the United Kingdom as well. For instance, within the United Kingdom, there are differences in how the word ‘scone’ is pronounced. Received Pronunciation would have read it as/skəʊn/, and would be printed in ITA as scoen, while speakers in Scotland would have pronounced it closer to /skɒn/, which would have been scon in ITA.

Having achieved mixed results or questionable efficacy, the ITA quietly faded out into obscurity in the 1970s, but the books, the experiences, and the memories live on. In early July 2025, The Guardian picked up on this story, bringing to light the legacy of ITA in the schoolchildren of the 1960s and 1970s who used it. The article emphasised that learning the ITA disadvantaged spelling later on in life, pointing towards the transition period from ITA to the English alphabet as a likely critical issue. Additionally, some individuals who were taught ITA reported having English as their worst subject in standardised examinations.

In a way, learning about the ITA experiment reminded me of the time Singapore simplified its own Chinese characters, rolling them out for 7 years before switching to the simplified Chinese characters used in the People’s Republic of China. This period was during a time when there was a need to boost or improve literacy, leading to the implementation of methods thought to make this process easier. But it also represented a period of confusion in how things were supposed to be written and how things were supposed to be read. Education and pedagogy are complex topics, topics that leave a lasting impression on the children that go through them. This attempt of simplifying the problem of how English is read has evidently left a generation of children to bear the full costs, whose effects mostly last to this day.

Read The Guardian article here: