The click consonants are perhaps some of the rarest or most unusual type of sounds used in the world’s languages, with this type of sounds being closely associated with the ‘Khoisan’ languages of southern Africa. Beyond this group of languages, however, there are only three languages spoken in eastern Africa that use click consonants, and only one once extant language in Australia which used this particular set of sounds. Today, we will take a look at one particular click language used in eastern Africa, one that is spoken by a rather genetically interesting people group as well.

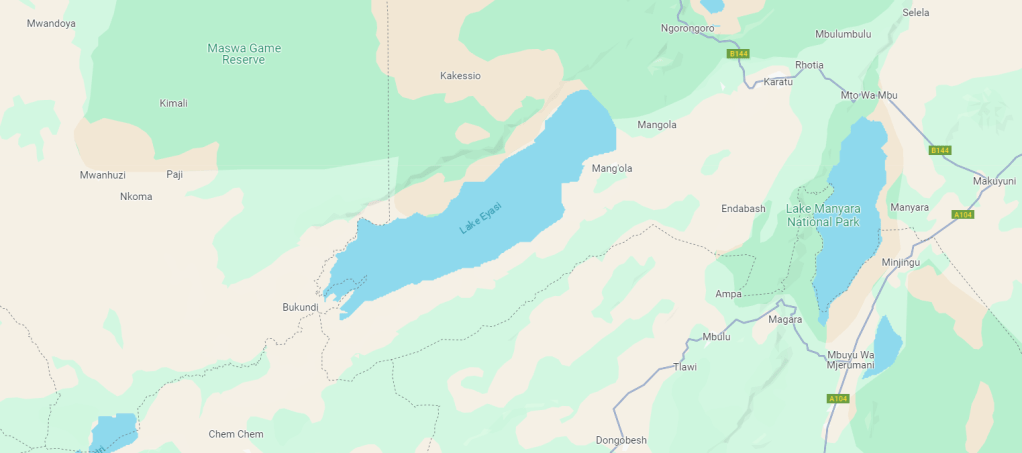

The Hadza, or Hadzabe, are a people group native to the Lake Eyasi basin in Tanzania who traditionally lead a hunter-gatherer lifestyle. Despite living in relative proximity to the Sandawe people, and by proximity we mean a distance of around 150km, the Hadza people are not known to be genetically close to any known population. This suggests that the genetic divergence between these populations go exceptionally far in time, going back thousands of years. In more recent times, however, there are interactions between the Hadza and Bantu people groups, with evidence of intermarrying and other forms of genetic admixture occurring between these populations. All of these would lead to some form of influence on the language they speak, Hadza.

Perhaps like the genetic relationship between the Hadza and other other populations, the Hadza language is not known to be related to other languages, with even the link with Sandawe language, or perhaps some of the ‘Khoisan’ languages being rather weak. In fact, the only proposed evidence of such linkage include the presence of click consonants, and perhaps a few cognates that might not be adequately substantiated. This lack of an attested genetic relationship with other languages is what is known as a language isolate.

One hypothesis, however, has attempted to link Hadza with the Chadic languages spoken mostly in the Sahel region by comparing lexical cognates between these languages. The main criticism drawn to this hypothesis was that some Hadza words could have been borrowed from the Chadic languages, rather than being a cognate. Additionally, some of these words might just be coincidences, just like the English ‘dog’ is a linguistic coincidence with the Mbabaram ‘dog’. Thus, with the current evidence at hand, Hadza’s status as a language isolate seems pretty set for now.

Spoken by around a thousand people today, by pretty much most of the Hadza ethnic population, there is active transmission of the language to younger generations. There are no attested dialects, just regional variation in some words, especially loanwords of Bantu origin. However, with increasing interaction with pastoralist people groups, and the increasing use of Bantu languages such as Swahili by the Hadza, there is some concern that language shift will occur in the Hadza people, with more people moving towards speaking the Bantu languages they interact with, and away from their traditional tongue. This has led to the vulnerable classification allocated to the Hadza language by the UNESCO Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger.

There are three types of click consonants used in the Hadza language, which may be transcribed in a similar fashion to those you would see in isiXhosa. Firstly, there is the dental click, transcribed using the letter ‘c’, articulated using the teeth, or with the alveolar ridge just behind them. There is also the lateral click, transcribed using the letter ‘x’, articulated using the side of the tongue. And lastly, there is the post-alveolar click, transcribed using the letter ‘q’, articulated using the back of the alveolar ridge, but generally not involving the hard palate (behind the alveolar ridge). In more layman circles, or at least that is how many would describe the sound, there is the tsk-tsk click, the horse-calling click, and the cork-popping click. These click consonants may also be distinguished by nasality, aspiration, tenuis, and glottalisation. Unlike the Khoe languages where click consonants predominantly occur at the start of a morpheme or word, click consonants can occur in the middle of a morpheme in Hadza, like one would encounter in languages like isiXhosa (like uxolo, ‘sorry’).

On top of the click consonants, the Hadza language is also particularly rich in consonants as well, distinguishing between pulmonic consonants and ejective consonants, while voicing distinctions are made between the /p/ and /b/ sounds in native words, and several other consonants in loanwords or nasal-consonant (NC) sequences. For the plosives and affricate consonants, some of these consonants may be distinguished by aspiration, tenuis, voicing, glottalisation (ejective consonants), and prenasalisation. This rich inventory of consonants is complemented by 5 vowels, the /a e i o u/ sounds, which are nasalised before the nasal click consonants.

Unlike the Khoe languages, which generally have three or four tones, Hadza does not seem to have an attested system of tone. And also, unlike the Khoe languages, the Hadza language is known for using medial clicks, meaning that click consonants can occur in the middle of a word that carries meaning. Khoekhoe, a Khoe language, tends to use click consonants on the start of a word instead. Compare words like minca [miᵑǀa] (Hadza, to smack one’s lips) with |nam [ᵑǀȁm̀] (Khoekhoe, to love). But of course, initial clicks like those seen in Khoekhoe also occur in Hadza words, such as cheta [ᵏǀʰeta] (Hadza, to be happy).

The Hadza language has a rich system of personal pronouns, which distinguish the third person not only by gender, but also by number and distance. These distances are called the proximal (close to the speaker), given, distal (far from the speaker), and invisible, with each one of them generally prefixed by ha-, b-, na-, and himigg-. Additional third person pronouns may also exist to reflect some other nuances in the language. This grammatical gender carries several characteristics; the masculine gender typically groups together words or things that are long and/or narrow, while the feminine gender, where the singular is suffixed by -ko, typically groups together words or things that are round or large. A pot may be treated as either grammatical gender depending on how it appears — a short or wide pot may be feminine, but a shallow pot may be masculine. I cannot locate at which point of a pot’s depth would denote the threshold between the grammatical categories though. Some distinctions are less clear or relatively obscure though. The word for a rock or a stone is haqqa-ko, taking on the feminine gender, but a boulder, a comparatively large rock, translates to haqqa, taking on the masculine gender.

There are generally a couple of ways in which adjectives can occur. The first involves a few so-called ‘bare-root’ adjectives, often used to refer to basic adjectives like ‘big’, ‘long’, and ‘tasty’. The second one involves the modification of verbs to make them attributive to the noun they modify. These adjectives must also agree with the nouns they modify, namely, in gender and number. Verbs can also take up to two object suffixes, which may distinguish between direct and indirect objects for some pronouns.

Additionally, the Hadza language is also notable for having two separate terms for some large animals, which include the prey the Hadza people would hunt for food. These are the generic animal terms, and the triumphant terms used for successful kills or finds. Interestingly, instead of nouns, these words are treated as verbs, and would take on suffixes denoting number and grammatical gender, for instance. These words generally start with the /ɦ/ sound (written ‘h’), although there are triumphant names that deviate from this pattern like teɬe/tíɬí for buffalo and ts’ono-we/-wi for wildebeest.

It should also be noted that some of these triumphant terms may refer to more generic groups of animals. For instance, the term hèpéʔ / hipiʔ may refer to various antelopes in the region like the greater and lesser kudu, and the bushbuck. hè!ŋé, on the other hand, is used to refer to spotted cats like cheetahs, servals, and caracals, hĩǀ’i is used to refer to some smaller antelopes like the dikdik, the red-fronted gazelle, and the klipspringer, while hatʃa-ʔe/-ʔi is used to refer to some species of swine like the warthog and the bushpig.

The Hadza language has a restricted number system, but with extensive borrowing of number terms. There are Hadza words for ‘one’ and ‘two’, but for anything larger than these, loanwords from other languages it has interacted with are used. And to express any precise quantity larger than ‘five’, Swahili numerals are used instead. This paucity of number terms has led to the claim that the Hadza traditionally ‘did not count’ prior to contact with the Bantu peoples, but it does not seem to be substantiated in any way. And so, this might leave room for some rather condescending opinion on the Hadza’s numeracy skills, even though there does not seem to be evidence to substantiate the claim that the Hadza traditionally did not count.

Like the Khoisan people groups, the Hadza people face an imminent threat to their own language. As some have already put their hunter-gatherer way of life aside in favour of more pastoralist or agriculturalist ones, there could be a language shift happening towards Bantu languages like Swahili, which is widely spoken in the region. While there are loanwords of Bantu origin in the Hadza language from the centuries in which the Hadza people have interacted with the various Bantu groups, we are not sure if loanwords from Swahili or English origin could replace or have already started to replace some Hadza words amongst communities today. For now, the Hadza language remains thriving, as language use is extensive within the Hadza people, and language transmission to the younger generations remains active.

Further Reading

Blench, R. (2008) ‘Hadza Animal Names’, 3rd International Khoisan Workshop.

Miller, K. (2008) ‘Hadza Grammar Notes’, 3rd International Symposium on Khoisan Languages and Linguistics.

Miller, K. (2009) ‘Highlights of Hadza Fieldwork’, LSA.

Sands, B., Maddieson, I. & Ladefoged, P. (1993) ‘The Phonetic Structures of Hadza’, UCLA Working Papers in Phonetics, 84, pp. 67-88.

Sands, B. (2013) ‘Phonetics and Phonology’, in Vossen, R. (ed.), The Khoesan Languages, Oxford, Routledge, sec. Hadza.

Sands, B. (2013) ‘Tonology’, in Vossen, R. (ed.), The Khoesan Languages, Oxford, Routledge, sec. Hadza.

Sands, B. (2013) ‘Morphology’, in Vossen, R. (ed.), The Khoesan Languages, Oxford, Routledge, sec. Hadza.

Sands, B. (2013) ‘Syntax’, in Vossen, R. (ed.), The Khoesan Languages, Oxford, Routledge, sec. Hadza.