Previously in this series, we have looked at one particular language spoken in Australia which uses a relatively rare system of case prefixes, albeit a rather simple one. There are also a couple other languages in Australia which supposedly use a system of case prefixes, with one of them, Gurr-goni, being somewhat related to the Burarra language we have covered. The other would be the language we will be looking at today, which goes by the name of Marra, or Mara.

Like Burarra and Gurr-goni, the Marra language is spoken in the Arnhem region in Northern Territory, more specifically the southwestern part of the Gulf of Carpentaria, and is classified as an Arnhem or a Macro-Gunwinyguan language. Marra, however, belongs to a different branch or family of the Arnhem languages, that being the Marran languages. There is a claim that suggests that Marra is one of the two surviving languages of the Marran languages, with the other being Alawa, though there are no further studies supporting or affirming this classification. If true, this would mean that Marra is most closely related to languages like Warndarrang, which lost its last known speaker in 1974.

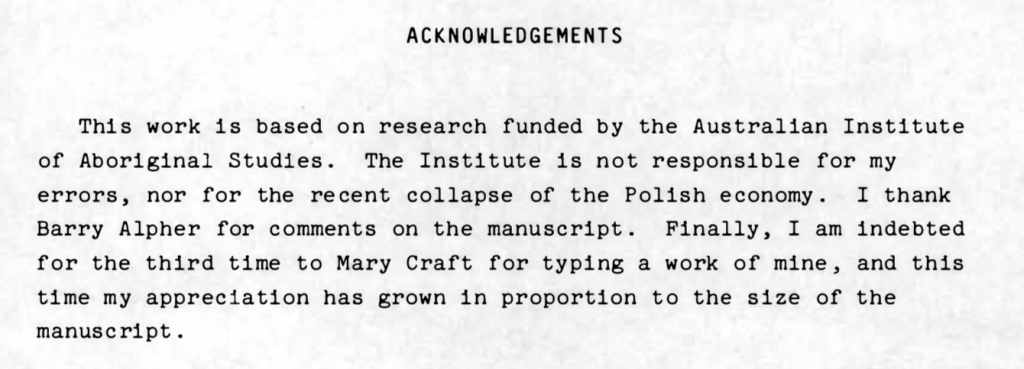

Most of the modern or contemporary research covering the Marra language was conducted by the linguist Jeffrey Heath, who has published materials covering Marra and Warndarrang. Margaret C. Sharpe would also make some publications covering the Marran languages as well, with a particular focus on the Alawa language that has been claimed to be part of this family. One of the primary resources concerning the language is the 1981 publication titled “Basic Materials in Mara: Grammar, Texts and Dictionary” by Jeffrey Heath, which contains one of the more unusual acknowledgements pages I have seen:

Marra has pretty much the ‘typical’ phonological inventory of an indigenous Australian language, you know, few vowels, no fricatives, five places of articulation distinguished by nasality, one /w/, one /j/, one /l/, and one /r/ sound, and some retroflex consonants added to the mix. There are a couple of additional sounds worth mentioning, such as the /n̪/ and /l̪/ sounds found in some terms for wildlife, which are articulated using the upper and lower teeth instead of the alveolar ridge. The vowel [o] only occurs in an interjection yo, and [e] only occurs in two words, renburr (paper wasp) and reywuy (sandfly). Additionally, Marra does not distinguish vowel length, although there are some differences when we talk about prosody.

One of the more bizarre phonotactic constraints Marra has is that no words may begin with a vowel in the language, with only a few exceptions for the /a/ sound. Additionally, there are no vowel clusters, and there is a system of lenition used in Marra for some consonant sounds. There is also a tendency to nasalise stops, especially when followed by a nasal or a non-stop consonant. Thus, some changes that may occur include /t/ becoming /n/, /p/ becoming /m/, and /k/ becoming /ŋ/.

It is time to mention the elephant in the room. How do words inflect for case in the Marra language?

The system of case prefixes has been documented for nouns, with different prefixes used for the singular masculine and feminine noun classes, neuter noun class, as well as the dual and plural numbers. However, like Burarra, this case prefix system seems rather simple. There are two forms of case prefixes used in Marra, namely the nominative, and the oblique. All nominative prefixes end in a consonant, or are zeroed, while oblique prefixes end in a vowel, with many nouns having some form of lenition when forming the oblique.

| Nominative | Oblique | |

| Singular, masculine | ø- | rna- |

| Singular, feminine | n- | ya- |

| Neuter | n- | nya- |

| Dual | wurr- | wirri- |

| Plural | wul- | wili- |

Heath remarked that these prefixes must be used, except when there is a pronoun prefix for “I’, “we”, and “you”, when there is a ‘pergressive’ case (to describe ‘in the vicinity’) involved, and in some occasions for the neuter nominative or the oblique in some speakers.

While Marra has a system of case prefixes, so too does it have a system of case suffixes, much like many languages across the world. Marra uses case suffixes to distinguish more discrete cases, in which there are six. These suffixes are used in conjunction with the case prefixes to reflect the noun’s role in a given clause, but essentially, the nominative case prefix is used with the nominative case suffix, while for all other case except the pergressive, the oblique case prefix is used with the respective case suffixes.

| Prefix | Suffix | |

| Nominative | Nominative | -ø |

| Ergative – Instrumental – Genitive | Oblique | -ø |

| Allative – Locative | Oblique | -y2u(r) |

| Ablative | Oblique | -y1ani (most nouns) -y1ana (place names) |

| Pergressive | None | -y2a |

| Purposive | Oblique | -ni |

The nominative case also functions as the absolutive case, depending on which alignment is used in the sentence. However, Heath preferred to use the term nominative as opposed to the absolutive to prevent confusion amongst these terms when comparing across other languages he has studied such as Warndarrang. The ergative case, on the other hand, is also used as the instrumental and genitive cases. After considering the purposive case, which expresses reason or purpose, the other noun cases express a movement towards (allative), away (ablative), at (locative), or in the vicinity (pergressive) of a certain location or thing.

And so, to say that the Marra language exclusively uses case prefixes is quite wrong, and perhaps it would be more accurate to say that the Marra language uses a mix of prefixes and suffixes to indicate grammatical case. Thus, the map shown in WALS Online might need some updating to reflect this.

With an extensive kinship system (refer to Heath 1981, pp. 96 – 129 for more details), the Marra language does stand out in this aspect of lexicon, especially amongst related languages in the area like Warndarrang. However, there is some avoidance speech used amongst the Marra speakers, such as men being not allowed to pronounce the names of some of their in-laws, and customs pertaining to the direct interaction between siblings of the same sex. However, this system of avoidance speech is not as extensive as those found in some other Australian languages.

Like most Australian languages, the Marra language has a restricted number system, with two unique number terms. ‘One’ is wanggij or wangginy, while ‘two’ is wurruja. ‘Three’ uses a special form, wurruja-gayi, which translates to ‘two another’, while ‘four’ literally translates to ‘two two’. To express ‘five’, Marra uses the phrase mani n-murrji, which translates to ‘like hand’. Higher numbers like 10 are formed from compounding these number terms, though expressing numbers like 120 is basically impractical, and less precise quantifier terms are used, like mijimbangu (many).

Today, the Marra language is in danger, with little evidence of language transmission to the younger generations. With fewer than 10 speakers recorded in the 2016 census, most speakers are now in their later years, and most of them, including ethnic Marra people, either use English, or use an English-based creole spoken by Aboriginal Australians called Australian Kriol. With no available or accessible action plan for language revival or revitalisation, there is great concern that the Marra language would be lost in the coming years. Nevertheless, there are some resources and dictionaries available for people interested in the language, such as through the Ngukurr Language Centre and the National Library of Australia.

Further Reading

Heath, J. (1981) ‘Basic Materials in Mara: Grammar, Texts and Dictionary’, Pacific Linguistics, Australia.

Sharpe, M. C. (1976) ‘Simple and Compound Verbs: Alawa, Mara and Warndarang’, Grammatical Categories in Australian Languages, Canberra, Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, pp. 708 – 734.

Sharpe, M. C. (2008) ‘Alawa and its Neighbours: Enigma Variations 1 and 2’, Morphology and Language History: In honour of Harold Koch, John Benjamins Publishing. pp. 59–70.