In some of the world’s languages, one would be no stranger to the concept of grammatical case. Briefly put, it is the word or word modifier that reflects one or more grammatical functions the modified word plays in a given sentence or clause. Sometimes these case systems are rather elaborate, often taking up the functions otherwise played by prepositions or postpositions, while some are reduced like in Bulgarian.

In most of these languages, these are often represented using suffixes, that is, modifiers that attach after the root word. But this is not the only way grammatical case is represented. Some languages choose to express grammatical case using clitics, which are basically unstressed words that can only be used with another word. Others change the root word, while some change the tone of the root word. There are also some languages that use prefixes, modifiers that attach to the front of the root word. And these are the languages I want to look into, and to start this off, I want to introduce you to the Burarra language, a Maningrida language related to languages like Gurr-goni, Ndjébbana, and Nakkara, spoken by around a thousand native speakers in the Northern Territory of Australia, according to the 2021 Australian Census.

The Burarra language is an exonym. Translating as ‘those people’ according to anthropologist Norman Tindale, the Burarra people who speak the language might call themselves the Ngapanga, although this claim seems to be unverified. Other names for the language and the people group that speak it include the Gidjingali. Today, most Burarra speakers live in the town of Maningrida in Arnhem Land, NT, which is also home to speakers of other Australian languages such as Ndjébanna. Most Burarra speakers are also multilingual, particularly the younger speakers, being fluent or at least conversational in English, Burarra, and other Australian languages spoken in the region.

Much of Burarra’s linguistic research has been conducted by David and Kathleen Glasgow, and a 1987 grammar sketch was written by Rebecca Green as an Honours Thesis, which is available on the Australian National University’s Open Research Repository. Such research typically involves some period of fieldwork working with the Burarra-speaking communities, such as Green’s work in Batchelor College (now the Batchelor Institute of Indigenous Tertiary Education) with Burarra students, and with Burarra speakers in Maningrida. However, publications in peer-reviewed journals on the grammar of this language are rather scarce.

Burarra distinguishes between 5 vowels (/i a u ɔ~o æ~ɛ/) in stressed syllables, and 3 vowels (/i a u/) in unstressed syllables. I cannot find information on whether vowel length is phonemically distinguished, however. There are 21 consonants in Burarra, with 5 places of articulation (bilabial, apico-alveolar, retroflex, palatal, and velar), distinguished by voicing and nasality. There are also lateral consonants /l/ and /ɭ/, as with rhotic consonants /r/ and /ɻ/. Lastly, there are the glides /w/ and /j/. This pretty much aligns with the typical pattern of phonological inventories of indigenous Australian languages, which generally lack fricative consonants like /s/ and /z/.

One defining feature of the Burarra language is its tendency to use prefixes rather than suffixes to modify a certain root word. We start to see examples of these prefixes in the noun class system used in Burarrra — it distinguishes a total of 4 noun classes, using prefixes to mark each one of them, especially for adjectives and verbs, and the indeterminate word -nga, which could translate as ‘whatever’, ‘someone’ or ‘something’. These noun classes are the an-, the jin-, the mun-, and the gun- classes, which are applied for the following types of nouns according to Glasgow and Green:

| an- | human males, some animals, some plants, vehicles, sand, fishing gear, the moon, lightning |

| jin- | human females, some animals, some trees, the sun |

| mun- | vegetable foods / plants that bear them, grass, some body parts, paper, pens, clothes, bedding, tins, aeroplanes, weapons, grassfires etc. |

| gun- | Liquids, some body parts, locations, ground, shoes, the other plants, fire, wind, rain, abstract nouns etc. |

The next set of prefixes you would encounter would pertain to this very topic — case prefixes. But there is a catch. When we look at the glosses provided by Green and Glasgow in their respective works, we do not really seem to find a system of case prefixes. Yet, the World Atlas of Language Structures still classifies Burarra as a language that uses case prefixes. So what is going on here?

Green suggested that Burarra does not use case suffixes to indicate relationships between the agent and object, and the sole (remember the Made Simple post?). However, word order is remarked to be somewhat flexible, and so, the relationships between these elements in a given clause involve “cross-referencing on the verb”. The only situation where we would find case prefixes for nouns is for the locative/instrumental case (in/at [something], with [something]), where we would find the case prefixes ana-, ji-, mu-, and gu- for the respective noun classes. These also apply for adjectives as well, which inflect for this very case.

But what about the pronouns? It turns out that they do inflect for case, but do so by using suffixes instead. Pronouns here have suffixes for the cardinal (-pa) and dative (-la(wa), -wa) forms, while having unmarked ones for the possessive, and use another set of pronouns for the oblique forms (remember the oblique case?). Thus, to say that Burarra only uses case prefixes, or that Burarra uses only prefixes, it seems a bit inaccurate. Burarra does have a tendency to prefer prefixes, but it does have its own set of suffixes to be used in some specific situations, or with some specific word classes.

Like pretty much every other Australian language, the Burrara language lacks an extensive number system. In fact, some might propose that the Burrara language might not even have any number words at all, instead, a couple of precise number terms are derived from other nouns or words, and do not really stand as their own lexical class. These words are –ngardapa (one, alone, separate), which has to be conjugated for noun class, and abirri-jirrpa (two, two are standing). For ‘five’, one proposed alternative is arr-ngardapa arr-murna, which can also be translated to ‘the fingers on one of our hands’. However, the listed resource I found that mentioned this does not seem to trace back to any accessible word list or dictionary, though I have managed to locate where abirri-jirrpa may have derived from:

Green also mentioned that there are three basic colour terms in Burarra, which are –gungunyja (black), –gungarlcha (white), and –mugulumberrpa (red). And from the hyphen on these words, it suggests that these adjectives will have to agree with the noun class, number, and even case of the noun the adjectives modify, which appears as a prefix.

As Vaughan and Carter have pointed out, younger speakers are typically more multilingual, and reside in more urban settings like Maningrida. These settlements may present a crossroad for multiple languages to interact, and potentially influence one another. As with the Tunuvivi language we covered a long while back, as youth identity develops and evolves in urban settings, we might expect linguistic change to happen as well, such as the borrowing on words from other languages into the Burarra language, to the erosive phenomenon of language shift where one language is used preferentially to others in a multilingual setting, abandoning their traditional language altogether.

For now though, Burarra seems to be alive albeit endangered according to the Endangered Languages Project, with a general drive to promote bilingual or multilingual education in Maningrida to ensure continued vertical transmission of the Burarra language. There are also cases where talking books in the Burarra language are produced as well, ensuring the presence of literary materials in the language. There also seems to be a Burarra songbook according to this archive, intended for use in the bilingual programme available at the Maningrida Education Centre. Additionally, there are the grammar sketches and linguistics studies linked in Further Reading, which have formed the research behind this introduction, and I highly recommend you check them out.

Further Reading

Glasgow, K. (1981). Burarra phonemes. Waters, B. (ed.) Australian phonologies: collected papers, 15, pp. 63-89.

Glasgow, K. (1984). Burarra word classes, Papers in Australian Linguistics, 16, pp. 1-54.

Glasgow, K. (1988). The structure and system of Burarra sentences, Papers in Australian Linguistics, 17, pp. 205-251.

Glasgow, K. (1994). Burarra-Gun-Nartpa Dictionary with English Finder’s List, Darwin: Summer Institute of Linguistics, pp. 910.

Green, R. (1987). A sketch grammar of Burarra. Unpublished IVth Year Honours Thesis. Australian National University.

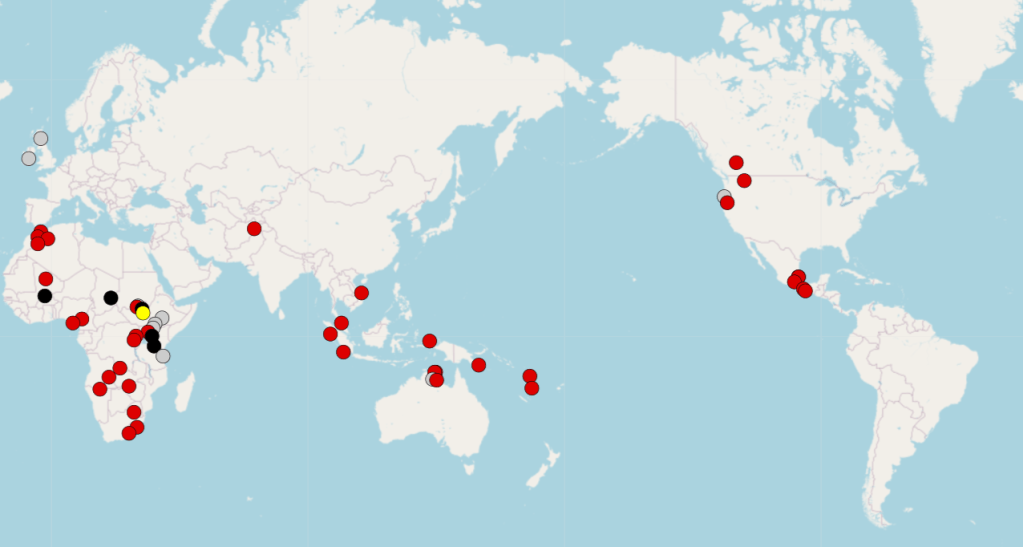

Dryer, M. S. (2013). Position of Case Affixes. Dryer, M. S. & Haspelmath, M. (eds.) WALS Online (v2020.3) [Data set]. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7385533 (Available online at http://wals.info/chapter/51, Accessed on 2025-02-21.

Tindale, N. B. (1974). Barara (NT). Aboriginal Tribes of Australia: Their Terrain, Environmental Controls, Distribution, Limits, and Proper Names, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-708-10741-6.

Vaughan, J. and Carter, A. (2022). “We mix it up”: Indigenous youth language practices in Arnhem Land. Global Perspectives on Youth Language Practices, De Gruyter Mouton. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781501514685-019.