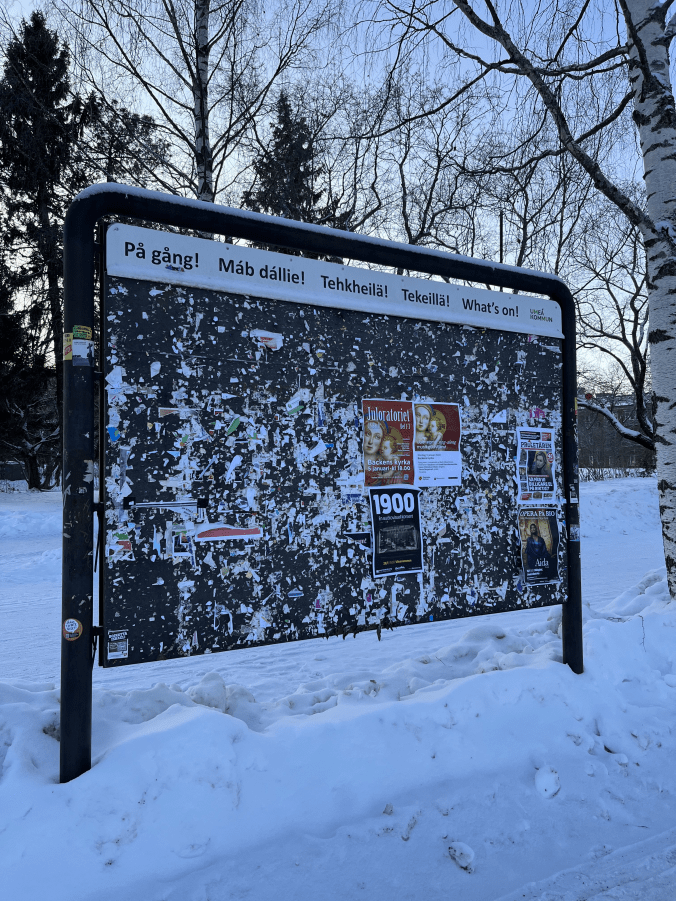

Remember that sign that I came across in Umeå, for which I wrote an introduction to Ume Sámi? I raised the question over where the word Tehkheilä could have come from, and posted it to the languages and linguistics community over in Bluesky, and received a rather compelling answer. It is perhaps a Finnic language that may or may not be a separate language from Finnish, and it is one of the more obscure languages that are spoken in Sweden. And so, for today’s introduction, I want to talk about this very language, and go over some of its more salient features.

This language goes by several names, depending on who you ask. Some might refer to it as Tornedalian or Tornedalen Finnish, hinting towards the location where the language is spoken, but it is natively known as Meänkieli, literally translating to ‘our language’. Meänkieli is predominantly spoken in Sweden’s northernmost region, which includes the Torne River Valley region, where the river marks part of the border between Sweden and Finland.

Whether or not Meänkieli is a separate language from Finnish, or a group of sub-varieties is under debate. On one hand, Meänkieli is largely mutually intelligible with Finnish, though on the other hand, Meänkieli diverged from Finnish since the creation of the Sweden-Finland border around two centuries ago. Arguments for the treatment of Meänkieli as a separate language include geopolitical ones, and its representation of cultural identity of the Tornedalians in Sweden. Other reasons also include the development of a standard orthography that is distinct from that in Standard Finnish.

Today, the Endangered Languages Project suggests that there are around 30 000 – 75 000 native speakers, with the most recently cited estimated being in 2015. Estimates are as low as 20 000 native speakers according to this 2010 source. Either way, the ELP suggests that Meänkieli is an endangered language, though the degree of endangerment varies based on the cited study. Most native speakers are bilingual or multilingual with Swedish and/or Finnish as well, with very few monolingual Meänkieli native speakers left. Despite its reported decline, there is evidence of intergenerational transmission of the language, which takes place at various educational stages, as well as through university-level courses offered in universities such as in Luleå and Umeå. Dictionaries and grammars are also available through Institutet för språk och folkminnen or the ISOF, suggesting decent documentation of the language today.

In any case, Meänkieli has been given separate catalogue codes from Finnish, such as its ISO 639-3 code [fit], and its Glottolog entry [torn1244]. Linguistically speaking, it is classified as part of the Peräpohjola group of Finnish dialects, with some of its most closely related dialects or languages (depending on who you ask) including Kven. In Sweden, Meänkieli consists of three sub-varieties, namely, the Torne Valley dialects, the Gällivare dialects, and Lannankieli. Like Meänkieli’s mutually intelligibility to Finnish, these sub-varieties are generally mutually intelligible with one another, although some further minor sound and lexical differences exist in each of them.

Typologically speaking, Meänkieli is generally similar to that in Finnish, but with some notable differences. Firstly, there is the letter ‘š’, which is actually introduced relatively recently to replace the digraph ‘sj’ that represents the /ʃ/ sound. Called the s-joka, this letter is present in some words that have received influence from Swedish. In these parts of Sweden, the ‘sj’ sound is more often realised as a [ʃ] than a [ɧ], and this is seen in Meänkieli words like informašuuni (information, Finnish tiedot).

Another difference is the prevalence of aspiration in Meänkieli compared to Finnish, marked by the letter ‘h’. In Meänkieli, aspiration of consonants occurs under certain grammatical contexts, such as the illative case (into [something]), passive verbs when a consonant is followed by two vowels, and perfect and pluperfect verbs. I thought that this might be explain why the word for ‘in progress’ or ‘what’s on’ in Meänkieli is tehkheilä, though the Finnish counterpart tekeillä seems to be treated as an adverb.

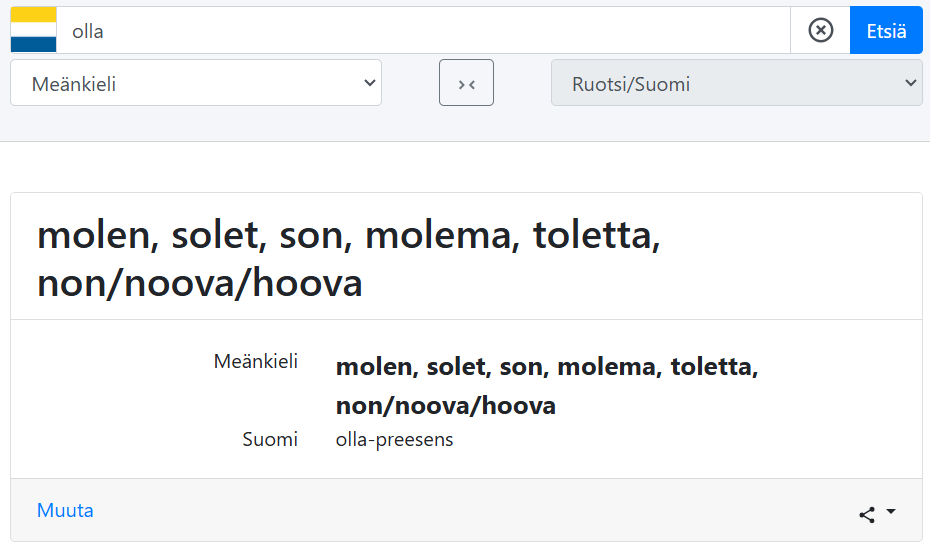

Meänkieli grammar is mostly similar to Finnish, from noun cases to verb tenses. However, in addition to some differences in case endings and conjugations, there are some salient features in Meänkieli that makes it distinct from Standard Finnish. One of the most notable ones I found was the conjugation of the verb ‘to be’ in Meänkieli. Here, spoken Meänkieli tends to contract the personal pronoun with the conjugated verb, something like how in spoken English, we tend to use contracted forms like ‘I’m’ and ‘you’re’.

There seems to be substantial influence from the Swedish language on Meänkieli as evidenced in differences in pronunciation of certain words, and certain lexical terms when comparing Meänkieli with Swedish and Finnish. For instance, the Finnish word for ‘apple’ is omena, and in Swedish, it is äpple. In Meänkieli, however, it is äpyli, which is most likely an influence from Swedish. Similarly, the Finnish word for the verb ‘to talk’ is puhua, and in Swedish, it is prata. The Meänkieli translation for this word is more similar to Swedish, as praatata.

Further influence from the Swedish language may be seen in the differences in how loanwords are pronounced (and also written). Where a [u] sound would occur in Finnish, for example, there would be a [y] sound in Meänkieli. Take for instance, the Finnish words kulttuuri and musiikki (culture and music respectively), and compare them with Meänkieli’s kyltyyri and mysiiki, and Swedish pronunciation /kɵlt’ʉːr/ and /mɵs’iːk/. The /ɵ/ sound is described as a close-mid central rounded vowel, which may be heard as a /ʏ/ sound, and hence would become a [y] sound in Meänkieli. Similarly, where in loanwords, the [o] sound would occur in Finnish, like in poliisi (police), a [u] sound would occur in Meänkieli, as in puliisi. In Swedish, ‘police’, or polis, is normally pronounced as /pʊl’iːs/. The presence of the /ʊ/ sound in the Swedish pronunciation could have influenced that vowel in Meänkieli, resulting in a [u] sound in Meänkieli.

Furthermore, there are Meänkieli words that seem to be identical to those found in Finnish, but have different meanings. One cited example is the word pyörtyä, which according to Institutet för språk och folkminnen, means ‘to faint’ in Finnish, but ‘to get lost’ in Meänkieli. There are also words that are unique to Meänkieli, not found in Finnish. Examples include porista (to talk), which translates to puhua in Finnish and tala or prata in Swedish, and sturaani (ugly), which translates to ruma in Finnish and ful in Swedish.

Lastly, there are some sound correspondences between Meänkieli and Finnish to be noted. The first example is how the [d] sound in Finnish words would be different in Meänkieli. In native words, this [d] sound would usually be omitted in Meänkieli, and be devoiced to [t] for loanwords. Compare the word syödä (to eat) in Finnish with syyä in Meänkieli. Gemination, or consonant lengthening, would also occur in Meänkieli where certain sounds occur in Finnish. For instance, the ts in Finnish would become tt in Meänkieli, as in katsoa in Finnish (to look) and kattoa in Meänkieli. Sometimes, the tk sound in Finnish would become kk in Meänkieli, and the v sound would be geminated in Meänkieli as well. Additionally, where the [v] sound would occur in Finnish loanwords, the [f] sound would occur in the Meänkieli counterparts, like väri (colour) in Finnish and färi in Meänkieli.

In Sweden, Meänkieli is recognised as a minority language, and Umeå Municipality is an administrative area for the language alongside the Ume Sámi language as we have introduced previously. This is perhaps one of the reasons behind the multilingual sign that I passed by in Umeå. This underscores the hidden linguistic diversity in Sweden, beyond Swedish and to a lesser extent, Finnish. So far, we have only covered the languages of Sweden’s northernmost counties, but there are also some interesting languages and Swedish varieties spoken further south. Maybe in future introductions, we could talk about the various varieties of Swedish like we did for German dialects, like Skånska.

Further Reading

Lainio, J. & Wande, E. (2015) ‘Meänkieli today – to be or not to be standardised’, Sociolinguistica, 29(1), pp. 121-140. https://doi.org/10.1515/soci-2015-0009.

Ridanpää, J. (2018) ‘Why save a minority language? Meänkieli and rationales of language revitalization’, Fennia – International Journal of Geography, 196(2), pp. 187–203.

Valijärvi, R. L. & Blokland, R. (2022) ‘Aspects of Meänkieli from a grammaticographical perspective’, Keel ja Kirjandus, 8-9, pp. 764-778.

A Grammar of Meänkieli, in Swedish (ISOF, 2022)