In language introduction essays done on this website, you might see these kinds of terminology thrown about without further elaboration given to them. For example, in some languages of Australia, you might have seen ergativity being used, as with the essay on Naukan Yupik and Chukchi. But what are these systems, and what kinds of systems exist in the world’s languages? And so, on today’s continuation of Made Simple, we will explore further in the field of morphology, and explore what kinds of systems there are.

The first linguistics term you would encounter when you search up this topic is morphosyntactic alignment. To simplify this, this is the type of relationship that occurs between a subject and an object of a simple clause or sentence (like “The dog ate my homework.”), or a single subject (like “I agree.”).

To further explain this, we have to mention the term called transitivity. This is the feature on verbs on whether or not they take direct objects. Intransitive verbs do not take a direct object (like “it is raining”), but transitive verbs do (like “I pet the dog”). As such, there is only one argument or linguistic expression that can occur for intransitive verbs, but two or more for transitive ones.

So, how do we examine the relationship between “the dog” and “my homework” in the transitive clause, and “I” in the intransitive clause? Well, the pattern in which these are treated would be a type of morphosyntactic alignment.

But before we move on to exploring the patterns we commonly see, we have to explain the different terms given to arguments in the various verbal contexts. There are at least three different flavours of arguments, depending on whose system of defining morphosyntactic alignment you are referring to. The most basic form follows Dixon’s 1994 definitions, which includes the sole (S), the agent (A), and the object (O). Sometimes, in place of the object, you might also encounter the term patient (P), but those terms essentially refer to the same thing.

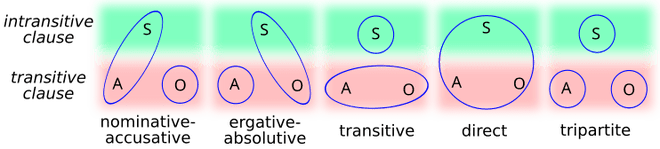

In today’s introduction, we will break down the main differences between the two predominant types of morphosyntactic alignment, although more types do indeed exist which will warrant their own introductions. But in any case, when we look for a visualisation of what we are dealing with here, we will almost always encounter this particular diagram:

And so, we will try to explain what the leftmost two mean here. Take note that morphosyntactic alignment can affect the case endings or case markers used, as well as the verb agreement, where appropriate.

Nominative-Accusative

Most European languages fall under this category of morphosyntactic alignment, with some of them boasting case declensions in their grammar. If you have learned, or are learning Slavic languages like Polish, Czech, and Russian, you would have seen such terms popping up during your course before. Similarly, in languages with more elaborate grammatical cases like Finnish and Hungarian, you would also encounter such an alignment, but with more nuance in the usage of some of these cases (Finnish partitive).

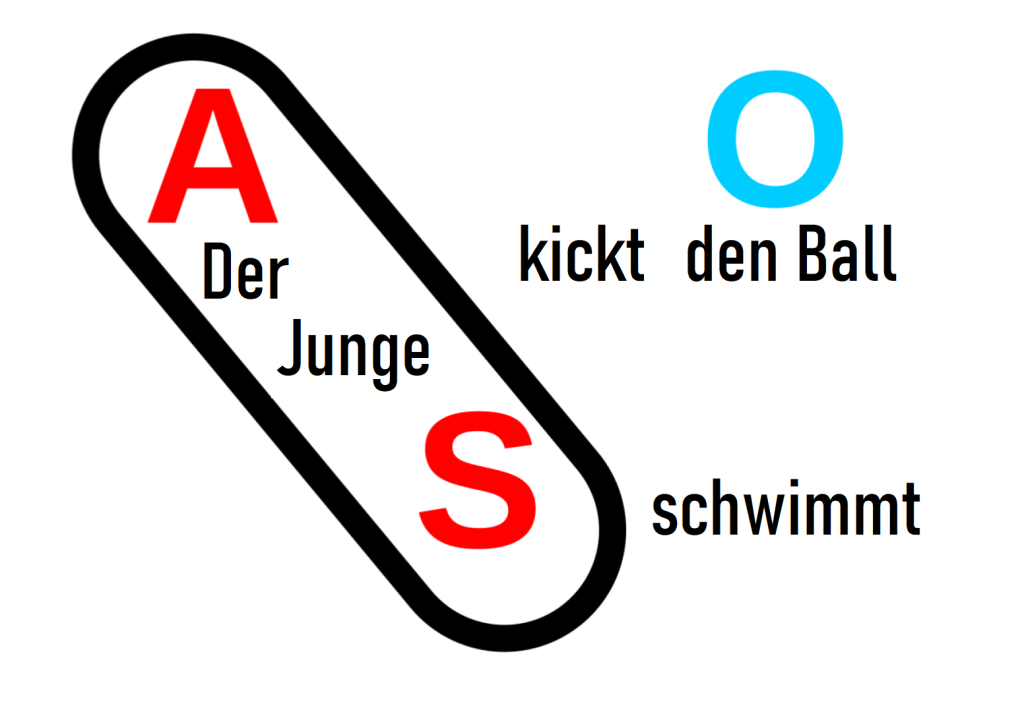

Some languages have a simpler way of marking this alignment, such as the use of definite articles (the) declined by grammatical gender, number, and case in German, or using the oblique forms of pronouns in English. To better illustrate the diagram we have seen earlier, let us take a look at the example below, showing the relationship between agent and object in the transitive clause (top), and the sole in the intransitive clause (bottom) in German:

English also has this alignment, although it was once more prominent in its history. With the extinction of case endings for it nouns, we see some vestiges in how the pronouns change depending on the role they play in a clause or sentence. Compare the following sentences:

- John is swimming.

- He is swimming.

- John hits me.

- He hits me.

- I hit John.

- I hit him.

In the first pair of sentences, we have an intransitive verb. English, as a nominative-accusative language, puts the pronoun ‘he’ in its nominative form. This form is also used in the second pair of sentences, in which John is the agent of the action ‘to hit’. However, this changes in the third pair of sentences, where the pronoun ‘he’ becomes the direct object of an action. This changes the pronoun ‘he’ to reflect the accusative case, but generally to mark it as an object. However, these pronouns are also used when forming the indirect object (‘to me’, ‘for him’ etc.), something that some languages would describe using the dative case. With such changes, sometimes you might also encounter this term called the oblique case, which marks the modified word as an object of an action, be it a direct or indirect object.

There does not seem to be a distinct geographical pattern where this morphosyntactic alignment is used, as it can be seen in numerous languages across the globe. Popular languages like English, Spanish, and Japanese use this particular type of morphosyntactic alignment, and so we might be alluded to believe that this is the only one out there. But this belief could not be more inaccurate.

Ergative-Absolutive

In Europe, there is one language today that stands out in contrast with the rest of the continent in the field of morphosyntactic alignment. That is Basque, a language isolate spoken in northern Spain and small parts of southwestern France today. Unlike pretty much every single language spoken in Europe, Basque boasts this particular alignment called the ergative-absolutive alignment.

In this alignment, the agent in a transitive clause is the one that is treated differently; the object or patient in the transitive clause and sole in the intransitive clause are treated the same. As I believe that most of us are more used to a nominative-accusative alignment, let us use a Basque example to illustrate what this alignment is.

Here, we have the two sentences,

- Gizonak Martin ikusi da.

- The man has seen Martin.

- Martin etorri da.

- Martin has arrived.

Martin is the sole in the intransitive clause, and the object or patient in the transitive clause. In a nominative-accusative alignment, Martin would have been treated differently grammatically, but in an ergative-absolutive alignment, Martin is treated the same way.

In Basque, case marking exists to exhibit this particular alignment. Martin, in both sentences, would be assigned the absolutive case, while ‘the man’, gizona, would receive the ergative case, which marks the agent of the transitive clause. Here, this is marked with the suffix -ak, -ek, or -(e)k, depending on the declension pattern the marked word agrees with.

Not every language does it like Basque does though, some Mayan languages do not bear such case markings, opting for the verb agreement route instead. Here, the verb agrees with the object in a transitive clause, and the subject in an intransitive clause. This is on top of agreement with person (I, you, it, etc.), and the number, tense, and aspect.

The modification of such words to reflect ergativity has been termed as morphological ergativity, as it affects the morphology of the word. But there are some languages that use an entirely different way of marking ergativity, not necessarily by changing the word itself, but by using a syntax geared towards ergativity. There are only a few languages that do this, and even fewer that use both morphological and syntactical ergativity. Some might do it by using a different word order, something that might literally translate to “I have returned” for an intransitive clause, and “The book I have read” for a transitive clause.

Fully ergative languages are somewhat rare across the world, and language hotspots featuring this alignment are generally found in specific geographical regions in the world such as Australia, New Guinea, Caucasus, the Americas, and the Tibetan Plateau. But what if I told you, that there are some languages that just use both, depending on the context in which it is required?

Split Ergativity

If you have learned a bit of Hindi or Urdu, you are likely to encounter the term called ‘split ergativity’. This would be marked by the suffix -ने (-ne), which has confused me a bit when learning this language in terms of its usage. Languages like Hindi and Urdu use a combination of nominative-accusative and ergative-absolutive alignments, often preferring one over the other in particular scenarios. While it can occur in some languages scattered across the globe, like some Mayan languages, and Sahaptin spoken in Washington, the languages that are most well-known for this feature is without doubt, Hindi and Urdu. And so, we will demonstrate an example of this using Hindi.

In Hindi, split ergativity happens based on the grammatical aspect used. There are three aspects used, namely, the progressive (ongoing state at a specified time), the habitual (an action that habitually occurs), and the perfective (an action seen as a complete whole). While a nominative-accusative alignment is usually used for the progressive and habitual, an ergative-absolutive alignment is used for the perfective aspect. Thus, to say “The boy has bought a book” in Hindi, in which “has bought” is an action seen as a complete whole, the suffix -ने (-ne) will be attached to the noun “the boy”, while the verb agrees with the patient, “the book”. Hence, this sentence will translate to:

लड़के-ने किताब ख़रीदी है |

lar̥ke-ne kitāb xarīdī hai.

As you have seen in the first diagram, there are other alignments that various languages around the world use to some capacity. In the coming introductions, we will introduce some of these main alignments, perhaps starting with the symmetrical voice, also known as the Austronesian alignment. Zúñiga’s publication on morphosyntactic alignment has served as a primary reference for this essay when exploring alignment types, which you can find here. There are also other articles I have found with has helped me in understanding the basics of ergativity, which I have linked in Further Reading.

Further Reading

The Ergative, Absolutive, and Dative in Basque (Wilbur, T. H., 1979)

https://www.culturanavarra.es/uploads/files/01-FLV31-0005-0018.pdf

Ergativity in Mayan languages: a functional-typological approach (Grinevald, C. & Peake, M., 2009)