The academic world is not new to controversial findings. From publications with conclusions that contradict long-held paradigms, to downright academic fraud and the direct use of generative artificial intelligence in writing manuscripts, it is safe to say that many of such discoveries and findings have come under heavy scrutiny by other subject matter experts. And in the field of linguistics, there is the study of one particular language which findings have divided expert opinion, and in my purview, could lay claim to the title of the ‘most controversial language’. This language is none other than Pirahã, or Apáitisí.

Spoken along the Maici River, a tributary of the Amazon, by around 400 people, according to most studies cited on the Endangered Languages Project, the Pirahã language is thought to be the only surviving member of the Mura language or Mura languages. The lines between dialect and language get quite hazy, but comparative studies between Pirahã and Mura suggested that Pirahã is a dialect of the Mura language. Today, the ISO 639-3 and Glottolog assign identical codes to each entity, treating them rather synonymously.

Attempts to link Pirahã with other languages have been tenuous. In fact, the first language linguists have tried to link Pirahã with is Matanawí, an extinct language so unknown the only record of it I can find is a word list in Portuguese published way back in 1925. Other relationships proposed pertained to the hypothetical Macro-Warpean language family by Terrence Kaufman in 1994. But other than that, Pirahã seems to be on its own today.

The first of the controversies, and perhaps one of the sources of them all, is that most of the linguistic fieldwork done on the Pirahã was essentially conducted by one person, by the name of Daniel Everett. Understandably, there are rather few linguists who have had some capacity of field experience in the Pirahã language and the Pirahã people. But this also means that there is not much of a second opinion from another field expert in the Pirahã language to affirm or dispute Everett’s claims. Fortunately though, there are some linguists might be embarking on this journey to study the Pirahã language more thoroughly, and test how well Everett’s claims hold. In other cases though, studies mainly used corpus data provided by Everett’s and Steve Sheldon’s fieldwork.

Pirahã phonology

The next, and perhaps the more minor controversy, pertains to the sound system of Pirahã. Alongside languages like Rotokas and Obokuitai, Pirahã lays claim to being the language with the fewest phonemic sounds, with as few as 9 or 10 phonemes in total, depending on how you analyse it. There are only 3 vowels, /a i o/, and some consonants that show a rather unusual distribution amongst Pirahã speakers. First of all, the consonants that are generally agreed upon are /p t ʔ s h/, with some allophonic variation (that is, variations that do not change the overall meaning of a word or utterance) observed as /b ~ m/ and /g ~ n/, with the nasal counterpart tending to occur at the start of the word. /t/ may be heard has [tʃ] when it precedes /i/, as with /s/ as [ʃ] when it precedes /i/.

The consonant receiving a large amount of scrutiny is the sound /k/. There are a lot of different realisations of the sound /k/ in Pirahã, with some remarks as it being an ‘unstable’ phoneme. Whether or not it is an allophone of some other consonant, is up for debate, as it has been documented, by Everett at least, that the /k/ sound may be analysed as [hi]. Additionally, when /k/ occurs at the start of a word, male speakers may use [k] and [ʔ] interchangeably, and [k] and [p] may also be used interchangeably by some speakers as well. To add onto this unusual variation of the /k/ sound, women may in turn realise the [h] sound as [s], and so the /k/ sound may be pronounced as [ʃi] by Pirahã women, at least according to Everett’s analysis of the /k/ sound.

Everett proposed that the Pirahã language has two tones, as low and high, with the high tone marked with an accent mark in his transcriptions. Sheldon, as we will see later, proposed 3 different tones, at low (3), mid (2), and high (1). Sometimes these would produce tone contours, with a high-to-low sounding like a falling tone, and low-to-high sounding like a rising tone. It is perhaps this feature of tone, and other phonotactic stuff like stress and prosody that allows Pirahã to be communicated through other audio means, like humming and whistling — a complete removal of consonants and vowels.

Another unusual feature of Pirahã phonology is Everett’s proposal of a couple of unusual sounds, recorded as [ɺ͡ɺ̼] and [t͡ʙ̥], which only occur in this particular language. He did remark that the [ʙ] sound, a trill articulated using the lips, occurs before an /o/, and he remarked that the [t͡ʙ̥] sound is used in private and not heard as much by the non-Pirahã. I cannot exactly verify this claim though, at least with the information I could find about these particular sounds. It could be the case that they are allophonic variations of the sounds mentioned above, but I think that the bottom line is, Pirahã has one of the smallest phonological inventories of any known language.

Pirahã words

Moving on with the controversies, we arrive at a particularly contentious issue when it comes to words for things. In the Pirahã lexicon, Everett has suggested that kinship terms do not extend beyond the immediate family, alongside the observation that Pirahã pronouns seem strangely similar to Nheengatu pronouns, a Tupi language spoken in the region. In the critique paper by Andrew Nevins, David Pesetsky, and Cilene Rodrigues in 2007, they looked into the claim that Pirahã had the simplest pronoun system amongst any known language. Here, the pronouns for I, thou, and he/she/it are ti, gí, and hi respectively. But in Sheldon’s 1988 analysis, however, he pointed out that there were indeed plural counterparts, suffixed by -xaítiso, a construction similar to how Mandarin Chinese plural personal pronouns are formed. The thing is, there are also claims that Pirahã may have borrowed its pronouns from Nheengatu, a claim that remains unverifiable because of the lack of information.

The only colour terms suggested were “light” and “dark”, which may be interpreted as “white” and “black”. Now, this is not all that surprising, especially when considering Berlin and Kay’s 1969 colour term hierarchy. This paucity of identified colour terms would put the Pirahã language in Stage I of this colour term hierarchy, alongside languages like the Yali and Dani languages in New Guinea, and the Bassa language in Sierra Leone. However, this identification came relatively recently, as previously, Everett claimed that there were ‘no colour words’, though Sheldon suggested that there were, according to Kay’s correspondence in 2007.

Additionally, according to Andrew Nevins, David Pesetsky, and Cilene Rodrigues in their 2009 publication titled “Pirahã Exceptionality: a Reassessment”, Everett’s word lists produced the following translations for colours:

| red / yellow / orange | biísi |

| blue / green | xahoasai |

| white / bright | kobiaí |

| black | kopaíai |

| dark | tioái |

| purple | tixohói |

However, Sheldon identified the following colour terms, using a different transcription system using numbers for tones:

| black | bio3 pai2 ai3 |

| white | ko3 biai3 |

| red / yellow | bi3 i1 sai3 |

| green / blue | a3 hoa3 saa3 ga1 |

Everett refuted Sheldon’s claims in his 2005 publication, citing that these terms were derived from other root words, like bii (blood) for red, “it sees” for bright or white, and immature for green or blue. This lead to Everett’s initial claim that there were no colour terms in the Pirahã language, as these words appear to ultimately derive from a construction of being [noun/phrase]-like. However, he also acknowledges that these could technically be interpreted as colour terms, just not structured like what we use in English, for example. That is, being morphologically simple. These words specify a particular colour space by similarity to objects the speaker is familiar with.

Pirahã numbers, or lack thereof

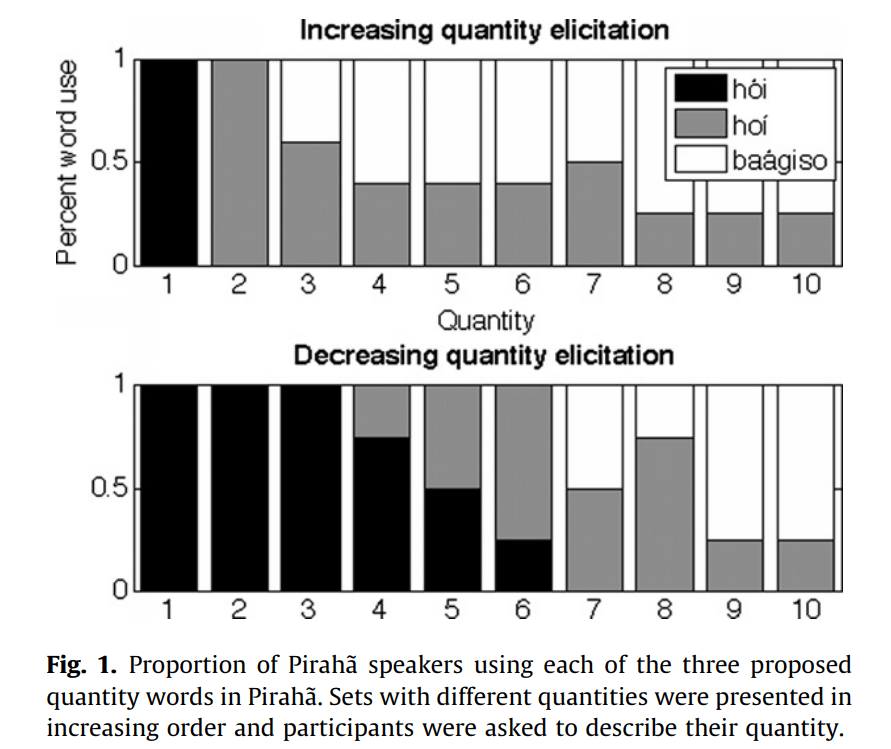

And perhaps the most controversial in the words of the Pirahã language, is the lack of precise number terms, and its implications on numerical skills of the Pirahã people. One of the more famous clips include this one on the Smithsonian Channel that showed how Everett approached the assessment of numbers and counting in the Pirahã language. Methodologies were better defined in articles like this one published in the Cognition journal in 2008, in which spools of thread were presented, starting with one spool and incrementally adding a spool until there were 10 of them, and with each quantity being quizzed using Everett’s translation of “How many is this?” in Pirahã. The same was done for decreasing quantities, starting with 10 spools, removing a spool at a time until there was only one.

From this study, three quantity words were identified, and I must say ‘quantity’ mainly because we are not sure if these words represent numbers at all. These are hói, hoí, and baágiso. Everett asserts that these do not represent precise quantities at all, instead representing “small amount”, “somewhat large amount”, and “many” respectively, with the following figure showing how blurry the lines get when distinguishing between precise quantities like ‘3’ from ‘8’.

This is far from the first study trying to elucidate number terms in the Pirahã language. A 2004 publication done by Peter Gordon reported the variant of baágiso, aibaagi, and he thought that hói and hoí represented ‘one’ and ‘two’ respectively, noting that these words do not have ‘exact meanings’. And so, hói could mean ‘around one’. In any case, in the 2008 study, it was noted that the linguists and anthropologists primarily involved in the study of the Pirahã language did not, or could not identify any other words that could come close as being ‘numerals’, and ultimately coming to the conclusion that the Pirahã language very likely lacked number terms.

The 2009 Reassessment by Nevins, Pesetsky and Rodrigues pointed out more terms that could describe quantities, including the word xaibóai meaning ‘half’, though they acknowledged that these translations might be inaccurate. Nevertheless, the authors noted that the phenomenon of a lack of number terms is not particularly unique for languages in the region, nor the world. For example, instead of numbers as a separate class of words, some languages in New Guinea use body parts to count, while many languages in Australia for instance, lack number words for quantities above 5 or 10. So, morphologically, Pirahã does not seem to stand out in the numbers game, but what is probably special is that Everett did not really identify a tallying system amongst Pirahã speakers, at least from the publications I have encountered. Whether or not this is driven by culture, as Everett appears to asset, remains to be seen, but it does show how contentious of an issue this has been.

Pirahã, Everett, Chomsky, and Universal Grammar

Lastly, and most importantly, we have the controversy that has drawn the ire of supporters of Chomsky’s paradigm of Universal Grammar. The idea of Universal Grammar, that there is an innate constraint on what the grammar of any human language can be, and children learning language will adopt syntactic rules that conform with that constraint under Universal Grammar, has been proposed by renowned linguist Noam Chomsky. The parameters concerning Universal Grammar have changed over the time since it was first proposed, even amongst linguists when discussing the predecessors of Universal Grammar. But the one key feature of Universal Grammar that Chomsky and several co-authors proposed and stood by was the feature of a capacity to have a ‘hierarchical phrase structure’.

Other terms you might encounter when looking into this feature include “embedding”, “recursion”, and “Merge”. This, as Everett defined, was the possibility of “putting one phrase inside another of the same type or lower level”. Essentially, sentences such as “I watched the boat disappear into the horizon” would have some sort of embedding, as this sentence could be broken down into simpler sentences “I watched the boat” and “the boat disappear[ed] into the horizon”. One implication of this is that languages with embedding would theoretically have sentences that can be infinitely long. Chomsky, Hauser, and Fitch described this “Merge” rule as the taking of two “discrete units” and combining them to form a new unit, also called a phrase. This rule may be applied iteratively to make more complex verbal structures. And this is what Everett thinks Pirahã contradicts.

In Everett’s publications, he continually asserted that Pirahã demonstrates ‘no feature of embedding’, and that this feature, alongside other controversies in its lexicon, may be influenced by the principle he defined as the “Immediacy of Experience Principle”, which was proposed to be deeply rooted in Pirahã culture. In this principle, there is a restriction of grammar and life to concrete and immediate experience, and an immediacy of communication of something, usually one event at a time. In other words, an utterance may only express a single event.

This assertion has definitely caused a stir amongst the linguistics community, and further sensationalised by conventional media, often with condescending effect. Coupled with the assertions of the lack of colour terms and precise number terms, one could imagine how a sensationalisation of these assertions, which have yet to be proven or disproven for certain, would paint the Pirahã people and language under a derogatory light. This narrative is definitely concerning, since I do not believe that any language should be seen as “primitive”, as every language in the world has, and is undergoing some form of evolution.

There are several aspects of embedding that Everett found no evidence for, including possessives, relative clauses, reported speech, and certain lexical terms involved in embedding. For instance, let us look at embedding via possession. In English, we can theoretically infinitely stack possessor-possession relationships, such as my friend’s brother’s son-in-law’s wife’s dog. Technically it is grammatically correct, and it shows several layers of embedding. But you cannot really do this in Pirahã, at least not according to Everett. In Pirahã, one way to make a possessive expression is to use the construction “I have a brother”, or “This is my house”. This is done by using a construction known as a “prenominal possessor”, essentially:

[possessor] + [possessed] + [3rd person singular pronoun] + [verb to be]

This cannot be recursively expressed in a grammatically correct fashion, and thus Pirahã has been argued to lack embedding or recursion in this particular context.

Another example is how one might interpret the suffix -sai in Pirahã. In Everett’s original analysis, he thought that Pirahã might express one level of recursion through this suffix, which was interpreted to be a nominaliser, basically a suffix that turns the word it modifies into a noun. But in his later analysis, he disagreed with his initial interpretation, arguing instead that there are actually multiple sentences involved in a sentence that appeared to have some form of recursion. One example is “I know how to make bread”, which could be translated as “I know bread-making” in Everett’s initial interpretation. But this could also be interpreted as “I know” and “making bread” in his subsequent analysis, with the suffix -sai marking the first clause as “old information” (refer to his 2009 response).

One way to get around recursion under his later analysis was to use this thing called ‘paratactic conjoining’, where two clauses are juxtaposed to express something that would be translated as something more grammatically complex. This also applies for sentences used to compare two things, like “The fish is bigger than the rock”, which takes two clauses “The fish is big” and “The rock is bigger”.

One point of contention is how one might interpret reported speech in Pirahã. The construction “He said that he liked fish” is in itself an example of recursion, as it demonstrates the embedding of one clause (He liked fish) in another (He said). Reported speech thus involves the attachment of the suffix -sai to the verb to say, -gái, as gái-sai. If we follow Everett’s new analysis of the suffix -sai, it could be interpreted that the action “said” is old information, and whatever that is quoted is new information. This contrasts with the initial interpretation of the suffix -sai as a nominaliser, which would have been interpreted as “[person’s] saying that [quoted speech]”, providing some leeway to argue for some form of recursion. However, the nominaliser interpretation would have entail further grammatical functions that were not accounted for, leading to some holes in this theory that Everett has argued against.

In Nevins, Pesetsky, and Rodrigues’ rebuttal, they asserted that the lack of the features discussed is not unique on their own, with examples of a similar lack of features being observed in other languages. Additionally, depending on how one would analyse Everett’s transcriptions and translations, such as the interpretation of the suffix -sai, there is still room to argue for the presence of some sort of recursion in Pirahã. For instance, Sauerland’s 2010 analysis, though unpublished, found that there was some tonal distinction in how the suffix -sai is used, which could lend some evidence for some sort of recursion in Pirahã. Nevertheless, Everett’s 2009 response maintained his argument for a lack of recursion, and still stands by it to this day. He argued that what might appear as recursion to us, would be realistically communicated via simpler, non-recursive sentences. These publications have been rather interesting reads, and I have only condensed some of the areas in which Pirahã has been argued to lack recursion or embedding. There are more features that I have not covered, but I definitely recommend giving them a read.

While corpus studies like this one suggested that there is no evidence of a ‘hierarchical phrase structure’ in Pirahã, at least according to the authors’ interpretations, thereby contradicting Chomsky’s proposition of Universal Grammar, linguists taking Chomsky’s side have vehemently countered these arguments using Everett’s character more than his claims, with Chomsky infamously reportedly calling Everett a ‘charlatan’. And according to this 2012 article, other ad hominem arguments by Chomsky supporters led to accusations of Everett being a ‘racist’ as he thought the Pirahã language falls outside the ‘linguistic norm’. Honestly, if I want to see Everett’s claims being criticised, once again, I would give Nevins, Pesetsky, and Rodrigues’ reassessment of the Pirahã language a read.

However, one criticism of Chomsky’s paradigm of Universal Grammar was that it is deemed to be unfalsifiable. This criticism has been aired by linguists (not necessarily on Everett’s side) such as Geoffrey Sampson, and even argued insofar as being “pseudoscientific”. Note that this criticism may also be held for Everett’s Immediacy of Experience Principle, as there are some aspects of the Pirahã language that cannot be feasibly tested for the involvement of Pirahã culture and this principle.

Perhaps the main takeaway is, for a long time in the study of the Pirahã language, much of its contributions was made predominantly by Everett and Sheldon. In essence, we do not have yet much other interpretation from linguists who would do fieldwork on the Pirahã language. But to hit back at claims arguing against a proposed linguistic paradigm with an ad hominem, it really makes these linguists seem juvenile or just straight up immature. In this essay, I have only scratched the surface of Pirahã grammar that one would argue for the lack of recursion, and simplified many more aspects to try to condense them to more communicable terms. I have linked various resources I think deserve a good read to get an overall grasp on the various controversies surrounding the Pirahã language, and perhaps you would be inclined to do your own research. Perhaps in the coming years, we would get more research and literature, providing some interpretations that could support, or disprove Everett’s claims about this particular aspect of the Pirahã language. Perhaps we just need more studies.

Further Reading

Comparison of Pirahã words with Mura and other languages:

Kaufman, Terrence. (1994). The native languages of South America. In C. Mosley & R. E. Asher (Eds.), Atlas of the world’s languages (pp. 46–76). London: Routledge.

Loukotka, Čestmír (1968). Classification of South American Indian languages. Los Angeles: UCLA Latin American Center.

Nimuendajú, Curt (1925). As Tribus do Alto Madeira. Journal de la Société des Américanistes XVII. 137-172. (PDF)

Salles, Raiane (2023). “Pirahã (Apáitisí)”. In Epps, Patience; Michael, Lev (eds.). Amazonian Languages: Language Isolates. Volume II: Kanoé to Yurakaré. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 957–994. ISBN 978-3-11-043273-2.

Phonology

Everett, Daniel L. (1986). “Pirahã”. Handbook of Amazonian Languages. Vol. 1. Berlin, Germany: De Gruyter Mouton. pp. 315–317. doi:10.1515/9783110850819.200. ISBN 9783110102574.

Lexicon

Everett, Daniel L. (2005). Cultural Constraints on Grammar and Cognition in Pirahã: Another Look at the Design Features of Human Language. Current Anthropology, 46(4), 621–646. https://doi.org/10.1086/431525

Frank, Michael C., Everett, Daniel L., Fedorenko, Evelina and Gibson, Edward. (2008). Number as a Cognitive Technology: Evidence from Pirahã Language and Cognition. Cognition, 108(3), 819–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2008.04.007.

Gordon, Peter (2004). Numerical cognition without words: Evidence from Amazonia. Science, 306(5695), 496–499.

Universal Grammar

Hauser, Mark D., Chomsky, Noam & Fitch, W. Tecumseh (2002).The Faculty of Language: What Is It, Who Has It, and How Did It Evolve?, Science, 298(5598), pp 1569-1579.DOI:10.1126/science.298.5598.1569

Interaction with Portuguese

https://journals.dartmouth.edu/cgi-bin/WebObjects/Journals.woa/1/xmlpage/1/article/409?htmlOnce=yes

The rebuttal and response

Nevins, Andrew, Pesetsky, David, and Rodrigues, Cilene. (2009). Pirahã Exceptionality: A Reassessment. Language, 85(2), 355–404. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40492871.

Everett, Daniel L. (2009). Pirahã Culture and Grammar: A Response to Some Criticisms. Language, 85(2), 405–442. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40492872.