Continuing from the deep investigation of unconventional number systems around the world, there seems to be an interesting pattern that is worth addressing. Many number systems we are familiar with tend to be in base 5, 10 or 20, with some of them having terms for higher numerals well into the thousands or millions and beyond. But there are also many languages that do not such an extensive set of numerals. Many of the Aboriginal Australian languages, for instance, usually have words for ‘one’ and ‘two’, but only a subset of these have words for ‘three’, and even fewer have ‘four’ and beyond. The Pirahã language too is well known for its supposed lack of precise numerals at all, yet, its speakers still demonstrate numeral literacy.

Based on a very naïve examination of the larger picture, we could sort of draw a rather crude pattern here. Languages that tend to have restricted number systems, if at all, tend to be spoken amongst hunter-gatherer societies such as Pirahã and ǃXóõ. Sometimes, body tallying systems are preferred to dedicating a separate lexical class to more complex numbers like ’25’. Sometimes, higher numerals tend to be borrowed from other languages rather than innovated de novo, although the latter does occur in some cases.

Now, we must emphasise the presence of counterexamples. There are hunter-gatherer societies that speak languages that do have an extensive number system, including the Iñupiat and Inuit peoples in the American far north and Greenland. Speakers of these languages have a base-20 system, which has unique number terms for 400 and 8000, and can be compounded to reach 4.096 quadrillion, a number so huge it is almost never likely to be used by anyone in daily conversation. Some languages on New Guinea also use the decimal system, with higher numbers up to 100 or 1000. Even the Nama language, a Khoe language spoken in Namibia and Botswana, stands out amongst its regional click language counterparts with its decimal number system, with words for 100 (ka̋ídȉísí) and 1000 (ǀòàdȉísí).

And so, this observation got me interested. I want to answer the following question today: Do languages of hunter-gatherer societies tend to have ‘simpler’ restricted number systems, or is this just a coincidence or perhaps a case of confirmation bias?

I must highlight that this observation has been highlighted by anthropologists, ethnologists, and linguists over the past century, with peer-reviewed publications looking into this surfacing in the past 50 years. However, this association was never quite systematically evaluated. That is, until the publication of this paper in 2012.

Here, Epps et al. assessed 193 hunter-gatherer languages spoken in 4 continents, Africa, Australia, North America (Great Basin and California), and South America, with some additional languages spoken by hunter-gatherers in Asia, and some languages spoken by pastoralists and agriculturalists in some corresponding regions. How these languages were selected was not exactly clear-cut, as the authors acknowledged that they did not control for language family, and hence some of these languages included in the sample may not be statistically independent; some linguistic evolutionary history could have played a role in shaping the number systems used in these languages that share a related history. However, the authors argued that controlling for this would reduce the sample size even further. In any case, this introduced a source of bias to the study, which limits how representative or generalisable the results are.

We define hunter-gatherer language here by that proposed by Harald Hammarström in a 2015 conference at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, which is a language which speakers subsist on a majority of plants and animals whose reproduction is not controlled by humans. This definition excludes pastoralists, who domesticate cattle or other kinds of large herbivores, and more obviously, agriculturalists, who have a farming lifestyle. The issue is, as seen in indigenous South American societies, the lines between hunter-gatherer and other forms of subsistence are not so clear cut. Some societies do practice agricultural albeit in a limited form, which can fall under a grey area at times. Additionally, trade between societies do occur between societies of different subsistence types, which can further blur such lines. As such, the authors tried to establish certain criteria to fulfill. This considered the time spent foraging for resources, proportion of wild food consumed in contrast to domesticated ones, and cultural importance of these activities.

Furthermore, ‘numbers’ in this study were defined as “spoken, normed expressions that are used to denote the exact number of objects for an open class of objects in an open class of situations with the whole speech community in question”. In essence, cardinal numbers like generic ‘one’, ‘two’, and ‘three’. This definition presents a broader set of problems, as some languages use counting terms for a specific type of object, which can differ from those of other objects. And so, the authors decided to include number systems that pertain to precise numerical values, loosening up the Hammarström definition by a bit.

| Hunter-gatherer | Pastoralist / Agriculturalist | Mixed | Total | |

| Australia | 122 | 0 | 0 | 122 |

| North America | 35 | 17 | 5 | 57 |

| South America | 19 | 105 | 62 | 186 |

| Africa | 17 | 13 | 2 | 32 |

| Asia | 7 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| Total | 193 (+7 Asian) | 135 | 69 | 404 |

So what were the main findings relevant to our question?

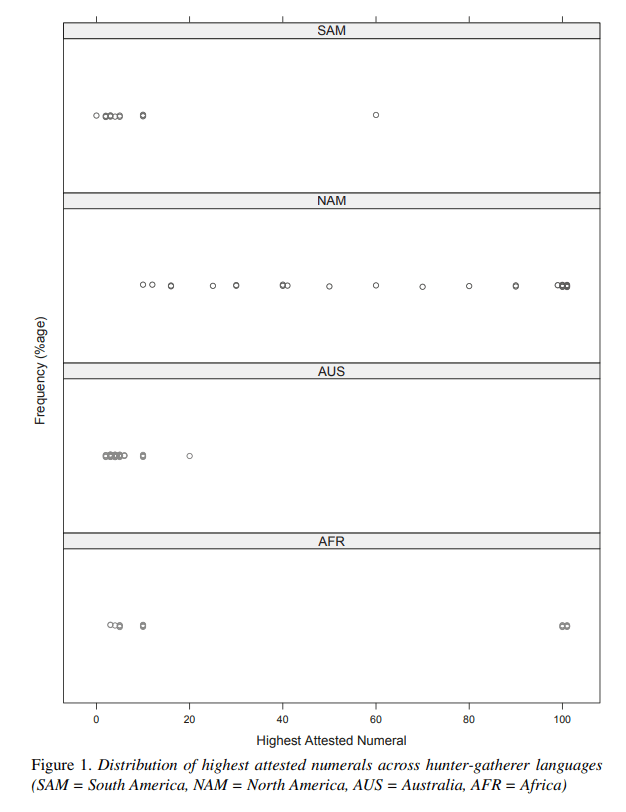

The primary finding is that the number systems used by these languages demonstrate considerable variation between continents, with most languages in Australia either having an ambiguous system or a restricted number system not exceeding 4, and the African languages sampled demonstrated a bimodal distribution in the highest attested numerals. This is more varied amongst languages in North America, although most languages there have highest attested numerals of at least 30, while South American languages tended to have smaller highest attested numerals. The highest attested numerals here are defined as the highest numerals that are native terms that refer to a specific quantity. Thus, if “8” is shown using fingers or loanwords, they do not count as a highest attested numeral.

The authors also found that in the Asian hunter-gatherer languages sampled, the ones spoken in Northeast Asia tended to have highest attested numerals of 100 or above, while those in Southeast Asia, namely the Aslian and Agta languages, tended to use number terms originating from non-hunter-gatherer languages, either through borrowing or languages shift. However, the inherited complexity of these number systems are somewhat preserved in the time since these words entered their respective languages.

And so, it would seem that there is more of a geographical association between languages and number systems used, rather than something alone the lines of subsistence type. However, the authors were only able to look deeper into the African and South American languages to evaluate the role of subsistence type in number systems. This is because all Australian languages are hunter-gatherer ones, and every single Australian language has a low highest attested number (the highest being Anindilyakwa with 20), making further analysis to distinguish between geographical patterns and subsistence type pretty much statistically impossible.

The sampled North American languages, however, exhibited rather similar distributions of number systems by subsistence type, although one agriculturalist language sampled has a highest attested number of below 20. And so, for a deeper analysis, the authors only reported statistics from African and South American languages.

From Figure 2, what is interesting in the South American sample is, while agriculturalist and mixed subsistence languages are more likely to have larger highest attested numerals than hunter-gatherer ones, there is still a substantial proportion of them that have rather low limits. If subsistence type does indeed play a role in shaping numeral systems, we would have expected that agriculturalist languages to have a substantially larger proportion of languages with higher attested limits in their number systems. With the counterfactual seeming to hold, the authors concluded that the practice of agriculture was not a sufficient need for the number systems to have higher limits. Precise statistics were not reported in the main manuscript, however.

In the sampled African languages, we see the reverse happening. Here, while agriculturalist and mixed subsistence languages have higher attested limits in their number systems, the hunter-gatherer languages are more varied, although they still account for pretty much all the sampled languages of attested limits below 50. No further comment was made regarding this finding, though they acknowledged some possibility of relevance of subsistence type in number systems of these languages.

Further findings were made related to the highest atomic number, that is, the highest number in a language that does not also refer to another thing, like a hand. Other reported findings pertained to the distribution of number bases and presence of multiple bases in these languages. But as my main question largely pertained to restricted number systems, I think that the highest attested limit in number systems would be the most relevant findings to dig into.

Before reading this paper, I thought that from the naïve observation of number systems and languages based on type of subsistence, one would be quick to point out that there is a heavy cultural association between the two factors. However, how such systems arose are not really understood. Perhaps some might have stemmed from how we count, like using the ‘hand’ to express 5, and ‘person’ to express 20 going by digit tallying. Others might have pointed out the need for trade, record keeping and verbal reporting because of the shift to agriculture, but even these have their own counterexamples (see Iñupiaq).

This is not to mention, the prevalence of cultural influences that can seep into the lexical category of the languages’ own numerals. We have seen examples in a previous essay before, that Austronesian languages have influenced some Papuan languages in Melanesia to adopt a quinary number system, while in turn, the Papuan languages could have also influenced the Austronesian languages to lose the decimal system. Not all of these languages are inherently spoken by hunter-gatherer societies as well.

Doubling down on this naïve pattern could lead to severely prejudicial implications. For one, going by the idea of linguistic relativity, the lack of higher numerals in restrictive number systems could imply that the speakers of these languages are less able to distinguish between large numbers or are poorer at counting or mathematics. I have seen discourse referring to languages spoken by hunter-gatherers, or languages with restricted number systems as “primitive”, which definitely did sound condescending, to put it gently.

But the idea that the lack of high numerals in these languages translates to poorer numeracy skills is rather inaccurate. Studies like this conducted on Aboriginal Australian children, who speak languages which generally lack numbers beyond 4 or 5, have shown that their numeracy skills are generally no different from those of English-speaking children. Other studies have also shown how speakers of these languages deal with larger numbers as well, such as the use of tally systems, or tally marks, to record the number of occurrences of a certain desired observation. This has also been observed in stone carvings dating as far back as the Stone Age, indicating that humans have had a capacity to count something, and record it as a tally. Therefore, it could be the case that, the world’s languages just expressed this tally differently, using whichever system they see fit and as needed.

From studies like the one by Epps et al. (2012), it seems that the association between hunter-gatherer languages and the type of number systems they have is rather spurious. The authors concluded that the type of subsistence is not the sole driver or factor behind the type of number system used. Instead, there could be other factors at play, such as those affecting social and cultural organisation, and those involving trade between other societies. Counterexamples mentioned in the introduction were also considered, as one would also question why languages like Iñupiaq have a complex number system if agriculture is a ‘prerequisite’ or ‘requirement’ for such a number system. Of course, there are still also questions left unanswered here. We must note that phylogeny or evolutionary relationship is not thoroughly evaluated as a factor, which would affect the independence of observations.

Nevertheless, given the predominance of restricted number systems in Australian languages, which are primarily hunter-gatherers with no contact with agricultural societies prior to European arrival, there is a possibility that the very first languages could have had a restricted number system too. After all, humans all started out as hunter-gatherers, and the shift towards agriculture in some populations only occurred more recently in our natural history (around 12000 years old). The question remains then, what was the very first number system spoken by humans?

Overall, I really enjoy encountering papers like this that test or challenge my initial preconceptions surrounding observations I have encountered. With each paper read, I just cannot help but to ask more questions, what the implications are, and what we can study further given the findings. I would like to see more systematic studies, preferably larger scale ones, studying the association between subsistence type and number systems, but with control of possible biases or confounding. Perhaps this way, the findings of such a study could be more representative or generalisable to the world’s languages. Building from this, I think that this is one area of comparative or computational linguistics worth giving a thorough look, to contribute towards building how the first number systems used by humans might have functioned.

Further reading

Butterworth, Brian & Reeve, Robert & Reynolds, Fiona & Lloyd, Delyth. (2008). Numerical thought with and without words: Evidence from indigenous Australian children. PNAS. 105(35) 13179-13184. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0806045105.

Epps, Patience & Bowern, Claire & Hansen, Cynthia & Hill, J. & Zentz, Jason. (2012). On numeral complexity in hunter-gatherer languages. Linguistic Typology. 16. 10.1515/lity-2012-0002.

Stampe, David. 1976. Cardinal number systems. Chicago Linguistic Society 12. 594–609.

Winter, Werner. 1999. When numeral systems are expanded. In Gvozdanovic (ed.) 1999, 43–54.