There is a saying that goes ‘fire is a good servant, but a bad master’. It describes the good that fire can bring to us, such as heat and light, serving us in our daily lives. Yet, it is capable of growing out of control, wreaking destruction in the form of blazes, infernos, and wildfires. I believe that the same can be said of radioactivity. For all the good it can bring us in advances in medical technologies and nuclear power, misuse and abuse have led to devastating effects in our health and environment. Yet, when one brings up the topic of radioactivity and radiation, our minds would instinctively conjure up thoughts about nuclear weapons, reactor meltdowns, and perhaps the quackery of radithor in the 1920s.

Deployment and testing of nuclear weapons and the aftermath of nuclear reactor meltdowns and fallout have resulted in several places laying claim to the most radioactive place on Earth. Some of these are completely abandoned save for a reluctant few, such as those living in the exclusion zone of Chernobyl, and the caretakers living on Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. Others have become tourist sites for people to visit, such as the evacuated city of Pripyat and Semipalatinsk. But in Iran, lies an entire city exposed to some of the highest doses of radiation year round. And it is not the result of nukes nor fallout; it is occurring naturally.

The city of Ramsar is home to around 35000 people, and is situated in the westernmost part of Mazandaran province in Iran, just bordering Gilan province. This city is also home to the most radioactive inhabited place on Earth, where the population is exposed to 10 times the annual limit of exposure to radiation every year, and some houses may contain radiation doses up to 80 times higher than the average background radiation occurring across the world.

This abnormally high radiation exposure is due to the local geology of the region, which contains rocks with uranium and its decayed counterparts such as radium and radon. Through erosion by underground water and other kinds of runoff, these radium deposits would make their way into the water and soil of the region, and consumed by the local residents. This has led to continued interest in understanding the effects of such extreme chronic exposure to radiation on human health, and epidemiological studies covering such topics.

While most of Mazandaran province speak Farsi today, residents also speak an Iranian language called Mazanderani. As we approach the western parts of the province, we also see Gilak populations as well, who speak the Gilaki language. This is also seen in Ramsar, which is mostly populated by the Gilak people, with some Mazandarani people living there as well. And so today, we will take a look at the language spoken in the most radioactive city on Earth, Gilaki.

The Gilaki language or gilɵki zɵvān belongs to the Iranian branch of the Indo-European languages, making it fairly distantly related to languages like English, and more closely related to languages like Farsi. Within this Iranian branch of languages though, it belongs to the Northwestern (and more precisely, Caspian) group of Iranian languages, making languages like Talysh and Mazanderani some of its closest cousins. It is spoken by around 1.5 million people today as a first language, and totaling around 3-4 million speakers, most of whom are Gilaks. However, the Gilak people are also fluent in Farsi, the official language of Iran.

The Gilaki language could be further broken down into three dialects, Western Gilaki, Eastern Gilaki, and Galeshi (or Rudbari, or Deylami). The Eastern Gilaki dialect, predominantly used in the regions of eastern Gilan and western Mazandaran where Ramsar lies, has received numerous influences from the Mazanderani language as well, with some sources suggesting that the dialect spoken in Ramsar is somewhere in between Gilaki and Mazanderani in terms of mutual intelligibility.

The Gilaki language has a total of 9 vowel phonemes, which includes 2 long vowels /i:/ and /u:/ and 7 short vowels /i/, /u/, /e/, /ə/, /o/, /a/, and /ɒ/. While Rastorgueva lists å as a open back vowel sound, take note that this is their own transcription of Gilaki vowels, and the International Phonetic Alphabet vowel is closer to [ɒ]. Additionally, Gilaki has a set of 22 consonants. However, this might be a bit different in Eastern Gilaki, as it has also received influences from Mazanderani, which lacks the 2 long phonemic vowels in Gilaki.

One phenomenon that is unusual to Gilaki is how vowel assimilation works here. Vowel assimilation is the feature where vowels change their quality to become similar to vowels in adjacent syllables (and perhaps more). In Gilaki, a regressive assimilation of vowels is observed. That is, the preceding vowel is altered to become similar to vowels in the following syllable. In the 2012 grammar publication by Rastorgueva et al., much of these assimilation occurs in how verbs agree with person and number.

The authors have also noted influences from Farsi as well, from well into Iranian history. Comparisons between Gilaki words and their counterparts in other Iranian languages such as Farsi, Balochi, and Kurdish were also made, noting a rather conserved pattern in words categories such as pronouns and numbers. Many Gilaki words are similar to those in Farsi, with some instances being remarked as loanwords of Farsi or Persian origin. Some have also noted how Gilaki words might be pronounced as if it was Farsi, such as the word ‘cooking’ poxtəpəz. If a strictly Gilaki pronunciation was followed, the word pəxtəpəz would have been expected, maintaining some consistency with its verb ‘to cook’, pəxtən.

Arabic has also influenced the vocabulary makeup of Gilaki, entering words in many aspects in life, such as religion, education, politics, and law. Some of these words might have been directly introduced to the language at some point in history, while others might have been introduced through Farsi, with the Gilaki meaning taking up something closer to that in Farsi than Arabic. Other notable languages of origin for Gilaki loanwords include Turkic languages such as Azerbaijani, European languages such as French and Russian, and perhaps more recently, we would see words entering from the English language as well. The publication lists many examples of such loanwords, which I think it is worth checking out.

The grammar of Gilaki is largely similar to that of other Iranian languages, sharing many similarities in how verbs work with languages like, once again, Farsi. Here, verbs are a closed class of words, with a limited number of simple verbs for some general actions. Like the other Iranian languages, Gilaki has a system of enriching this verb class by having compound verbs. These usually consist of a noun or an adjective and a verb. This makes up for the small number of verbs, and rather simple system of adding prefixes and suffixes to verbs to form new ones. For example, there is dust daštən (to love), derived from dust (friend) and (daštən).

The noun case system works a little differently, however. Gilaki is said to have a total of 3 cases though others may say it is a quasi-case. These are the nominative case, and as Rastorgueva et al. described it, 2 ‘oblique cases’. The first of which is the accusative-dative case, which generally marks objects, plus other grammatical functions, and the second is the genitive case. This sort of differs from Farsi, as Farsi only has a nominative and an accusative case. To denote possession in Farsi, one of the constructions used is the ezâfe, where an e is attached to the possessed noun, which comes before the possessor.

But back to Gilaki. Unlike some languages that use the accusative case with the verb ‘to have’, marking it as a directive object, Gilaki uses the nominative case instead. For indirect objects, the nominative case is also used for objects of place, time, measures and degrees, and form of action (like step by step). The accusative-dative case is instead used to mark direct objects of other verbs, and indirect objects featuring a benefiting party, for example.

Gilaki also uses the ezâfe construction mentioned previously and it is likely a direct borrowing from Farsi itself. However, the genitive case is reserved for another set of functions. In this language, the genitive case is used in combination with an elaborate set of postpositions, and used to modify some aspect of a certain noun (like describing ‘children’ as ‘unwell’). The use of postpositions in Gilaki contrasts with that in Farsi, which uses prepositions. To clarify, postpositions come after the word it intends to give further information to (like the box-inside), while prepositions come before the word (like inside the box). Adjectives may have some case endings, but generally do not agree with the nouns they modify.

There is also a report on how reported speech works in Gilaki, as according to Völlmin, the quotative marker -ə is used after every single verb used in the quoted sentence, and it might also be used after the verb ‘to say’, such as bugoftǝ (he/she/it said). To address the first person pronouns in quoted speech, there seems to be a preference towards the used of xu (self) instead of mǝn (I), even though the way reported speech works makes it clear that you could say “I”, “me”, or “myself”, without actually referring to you, the speaker. And to make things a bit more complicated, sometimes, this -ǝ suffix might not even be used.

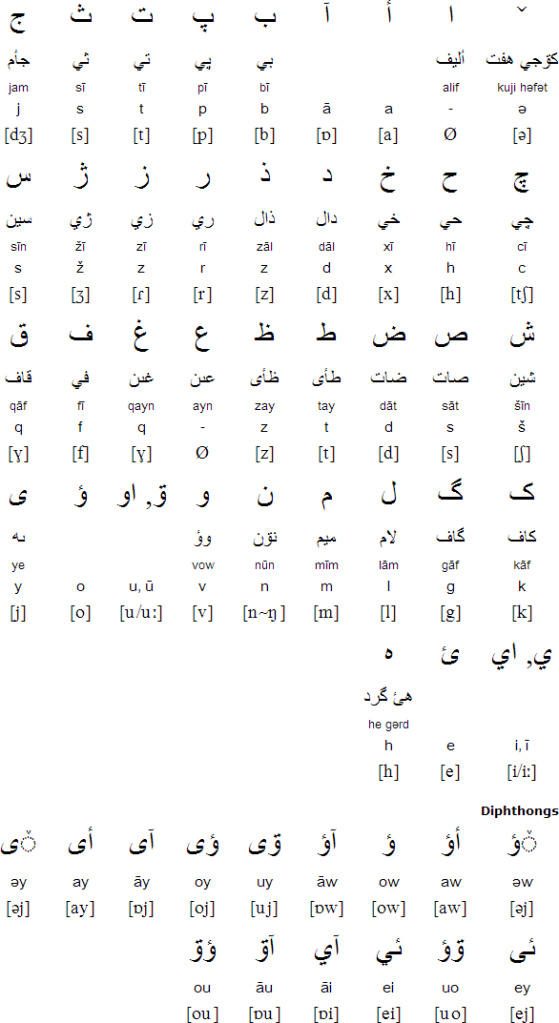

Gilaki may be a predominantly spoken language, but there has been efforts made to publish works in the Gilaki language over the past several decades. It is also written using a modified Perso-Arabic script, which includes modified letters and more diacritics to capture sounds present in Gilaki but not in Farsi nor Arabic. Like other Perso-Arabic scripts, the Gilaki script is written and read from right to left, with a system of letter joining bearing resemblance to a semi-cursive script.

Although education in Ramsar, and pretty much the Gilan and Mazandarani provinces are conducted in Farsi, the Gilaki language is thriving for now, with some evidence of its use at home or in colloquial speech, and language transmission mainly occurring within the household. Whether or not this is sustainable is up for debate, but with increasing access to written and digital media in the Gilaki language, there might be some optimism about the survival of the language in the future.

Further Reading

Gilaki grammar, Rostargueva et al. (2012)

https://uu.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:560728/FULLTEXT02.pdf.

Quotative marker in Gilaki, Völlmin (2019)

Another brief intro to Gilaki, Omniglot