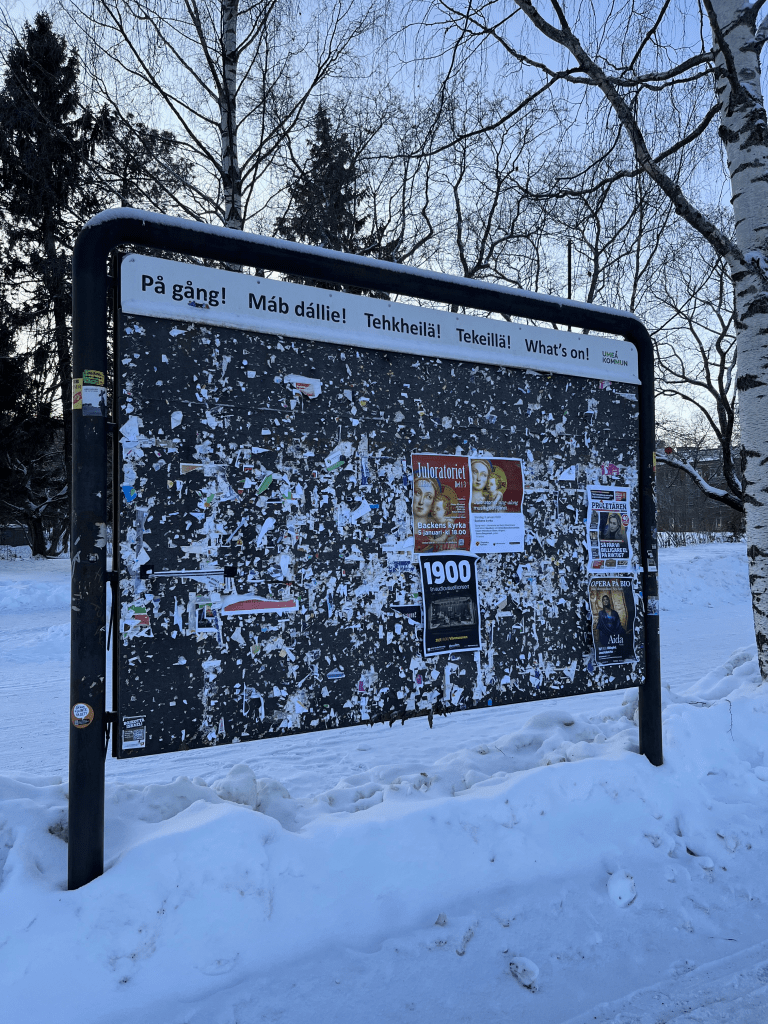

A while ago, I traveled to Umeå in Västerbotten County in Sweden. It was there when I came across signs like these, on which upcoming events in the city are posted. But it was not the events that caught my attention, but more rather, the languages which are featured on the signs themselves.

While I recognise Tekeillä and Tehkheilä are Finnish and some sort of Finnish dialect or Finnic language respectively (like the one spoken in Vaasa across the Gulf of Bothnia or around the Torne River), and of course, På gång is Swedish, the phrase Máb dállie did not look like any of the languages I know of or heard of. That was until I learned about the history of this place up north, closer to the Arctic Circle than the capital city of Stockholm today.

In parts of northern Sweden, Norway, Finland, and the Kola Peninsula of Russia, there are several indigenous people groups collectively known as the Sámi peoples. While they are best known for their reindeer herding way of life, there are also different ways of life, such as fishing for coastal populations, and fur trapping. The Sámi people groups traditionally speak various languages called the Sámi languages, which belong to the Uralic language family. This makes these languages related to Finnic languages like Finnish and Estonian, and even more remotely, Hungarian.

Here in Umeå, named such because the city straddles the Ume River, which in turn derives from Old Norse Úma (roaring), there have been historical evidence of nomadic Sámi before settlement by the Germanic peoples. Over time, the Sámi would have been pushed further inland. And today, in Västerbotten County in Sweden, the Sámi who live along the Ume River would most likely belong to the Ume Sámi, who traditionally speak Ume Sámi, or natively known as Ubmejesámiengiälla.

Ume Sámi is more precisely classified as a Western Sámi language, and is most closely related to Southern Sámi or åarjelsaemien gïele, while its next closest cousins are Lule Sámi and Pite Sámi, and more distantly, Northern Sámi. According to the Endangered Languages Project, literature quoted in the entry for Ume Sámi puts the number of native speakers today at just around 20, as recently as 2011, and it is likely that most of these native speakers are older adults or in the grandparent generation now. In fact, in Rasmussen and Nolan’s publication (linked in Further Reading), intergenerational transmission of Ume Sámi has been reported to occur in only one family. Even though there are Ume Sámi living in Norway and Sweden, the language is no longer spoken in Norway. Today, Ume Sámi is mainly spoken in Sorsele in Västerbotten County, and Arvidsjaur and south of Arjeplog in Norrbotten County in Sweden.

There is reported to be dialectal variation in Ume Sámi, which exhibits an northwest-southeast divide. For instance, northwestern variants include those spoken around the lakes Maskaure and Ullisjaure, and they generally have more influence and similarities shared with Southern Sámi. Southeastern variants include those spoken in Malå and around the lakes Mausjaure and Malmesjaure, and they generally share more similarities with Pite Sámi. In addition to lexical differences in Ume Sámi varieties, there are also notable phonetic and grammatical differences, especially in the copula verbs and negative verbs. The accusative case ending for the singular is -p in the northwestern varieties, and -w in the southeastern varieties as well.

Ume Sámi is reported to have 7 short phonemic vowels /i y ʉ u e o a/ and 6 long phonemic vowels /i: ʉ: u: e: o: a:/. There are also four diphthongs identified, which are /ʉi/, /ie/, /yʉ/, and /uo/, and some vowel sounds may share allophonic variation with the /ə/ sound. This is complemented by 17 consonants /m n ɲ ŋ p t k t͡s t͡ʃ v s ʃ h ð r l j/. The /v/ sound also exhibits allophonic variation with /f, ʋ/, while /ð/ also has allophonic variation with /θ/, though some western varieties lack this sound altogether. Pre-aspirated consonants are also a notable feature in Uralic languages like Ume Sámi, wherein there is an aspiration or voicelessness that comes before the closure of a certain obstruent, which may be transcribed as [ʰk] or [hk]. In Ume Sámi, pre-aspiration occurs before the sounds /p t k t͡s t͡ʃ /.

Ume Sámi is documented to have eight or nine noun cases, depending on how the abessive case is interpreted, which are declined by number (singular and plural) as well. These are usually organised into three types, grammatical cases (nominative, accusative, genitive), local cases (illative, inessive, elative), and adverbial cases (comitative, essive, abessive). Generally speaking, plural cases are normally marked with a /j/ sound, except the nominative, where they are marked using /h/. When conjugating personal pronouns, however, there are three numbers distinguished, which are the singular, the dual, and the plural. The following table is based on the analysis by von Gertten’s 2015 thesis, where a nine-case system was proposed.

| Case | Singular | Plural |

| Nominative | – | /h/ |

| Accusative | /v/ | /jtə/ |

| Genitive | /n/ | /j/ |

| Illative | /jə/, /ssə/ | /jtə/ |

| Inessive | /snə/ | /jnə/ |

| Elative | /stə/ | /jstə/ |

| Comitative | /jnə/ | /jkʉjmə/ |

| Essive | /t/ | /htaah/ |

| Abessive | /nә/ | /nə/ |

Like most other Finnic languages like Finnish, Estonian, and most other Sámi languages, Ume Sámi has this feature called consonant gradation, where consonant qualities mutate under some grammatical and phonotactic contexts. For instance, sukka (sock) in Finnish becomes sukan in the genitive. Ume Sámi verbs have two basic tenses in contrast to the four seen in Finnish, the present, and the preterit, also known as the simple past tense. Another shared similarity is the use of the negative verb, which is conjugated based on person, number, and tense. This verb paradigm is provided below, from von Gertten’s 2015 thesis:

| Present | Preterit | |

| Sg, 1. | ib /ˈip/ | idtjuv /ˈitʧəv/ |

| Sg, 2. | ih /ˈih/ | idtjh /ˈitʧəh/ |

| Sg, 3. | ij /ˈij/ | idtjij /ˈitʧәj/ |

| Dual, 1. | eän /ˈien/ | *iejmien /ˈiejmien/ |

| Dual, 2. | *iehpien /ˈiehpien/ | *iejdien /ˈiejtien/ |

| Dual, 3. | eägán /ˈiekaan/ | iejgán /ˈiejkaan/ |

| Pl, 1. | iehpie /ˈiehpie/ | iejmieh /ˈiejmieh/ |

| Pl, 2. | *íhpede /ˈiihpətə/ | *iejdieh /ˈiejtieh/ |

| Pl, 3. | eäh /ˈieh/ | idtjan /ˈitʧən/ |

| Sg, Imperative | ielieh /ˈielieh/ | |

| Dual, Imperative | *iellien /ˈiellien/ | |

| Pl, Imperative | *ilede /ˈiilәtə/ |

Since the turn of the 21st century, there has been notable progress to document, preserve, and potentially revitalise Ume Sámi. Firstly, orthography. Despite being the first Sámi language to be written down, there has never been a standardised orthography for the language until 2010, with the most recent version being rolled out in 2016 by the Working Group for Ume Sámi. Secondly, documentation. There have been contemporary efforts to compile dictionaries and grammars of the Ume Sámi language, with the most recent Ume Sámi – Swedish dictionary being published in 2018 by Henrik Barruk, and some salient features of its grammar have been the subject of theses like the one by von Gertten in 2015. Lastly, education. This one is a bit more difficult to come by, although there is substantial interest to learn the Sámi languages in general. Umeå University has been involved in organising courses in Ume Sámi in the 2010s, but I am unsure if it is still being conducted today. Many resources are available in Swedish, Norwegian, or Finnish, however.

When it comes to the revitalisation of Ume Sámi, I think this account in the Norwegian news site NRK by Sara Ajnnak, a Sámi parent, puts it quite well. Translated from Norwegian, “For us to succeed in the revitalization process, it is not just the teachers that are needed. We need the necessary teaching materials, dictionaries and enthusiastic people who are involved in the language.”

Further Reading

Larsson, L. G. (2012) ‘Variation in Ume Saami: The role of vocabulary in dialect descriptions’, Networks, Interaction and Emerging Identities in Fennoscandia and Beyond, pp. 285-298.

Rasmussen, T., & Nolan, J. S. (2011) ‘Reclaiming Sámi languages: indigenous language emancipation from East to West’, International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 209(2011), pp. 35-55.

von Gertten, D. Z. (2015) ‘Huvuddrag i umesamisk grammatik’, Master’s thesis, University of Oslo.