When it comes to hotspots of linguistic diversity, we tend to gravitate towards regions like New Guinea, Nigeria, and the Caucuses. But in the region of Melanesia, there are a group of 82 islands forming the nation of Vanuatu, which boasts the highest linguistic diversity per capita in the world. With a population of around 330 000 and over 130 indigenous languages spoken in the country, that translates to each indigenous language being spoken by around 2500 people today. Each and every language here is written in the Latin alphabet, but there is an interesting movement that has birthed a new writing system in the nation.

On Pentecost Island, there is a writing system that appears to be a bunch of loops and other geometric patterns. You might see them painted on signs, or carved into stone. This is actually used to write the Raga language, an Austronesian language, but it is also used to write related languages on Pentecost Island, as well as English, and the Vanuatuan English-based creole, Bislama. This writing system is actually rather recent, but it is birthed from a Vanuatuan tradition.

You see, Vanuatu has a strong tradition of using sand drawings (sandroing in Bislama), where oral traditions, genealogies, histories, and songs are encoded in a visual mnemonic, as literal lines in the sand (or volcanic ash). This is a rather intricate art, as these geometric shapes can encode quite a fair bit of information, including several meanings and interpretations. Today, sandroing has gained recognition by UNESCO, and there has been efforts to safeguard this tradition (or kastom) as it is steadily being sensationalised by tourism or commercial means.

It is this tradition from which Chief Viraleo Boborenvanua drew inspiration for an indigenous writing system for the ni-Vanuatu, further driving his aims in the Turaga indigenous movement in Pentecost Island. Thus, in a process that took 14 years, this writing system to be used in Pentecost Island would take shape. Its name drew from the Raga words for ‘talk about’ and ‘draw’, forming a compound word called Avoiuli.

The letters of Avoiuli could be joined together in a sort of cursive pattern, meaning that entire words could be written in a single stroke. This might harken back to sandroing, where entire geometric shapes could be drawn in the medium from a single stroke, using a single digit. There does not seem to be a distinction from uppercase letters other than character size, and they are hardly ever used in everyday life anyway.

Writing directions might vary a bit depending on context. On signs, some have noted that words are written right-to-left, while other texts may alternate right-to-left and left-to-right by line, with letter shapes written in reverse of the previous line. Some might just stick to the convention used in the Latin alphabet, and written entirely left-to-right.

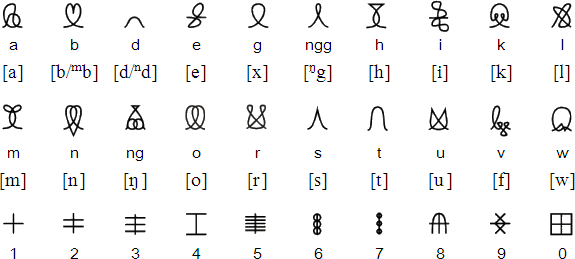

Avoiuli letters are almost a one-to-one correspondence to the Latin alphabet counterparts used by the languages Avoiuli represents, with the exceptions for the letters corresponding to ‘ng’ and ‘ngg’, and the omission of the letters ‘c’, ‘f’, ‘j’, ‘p’, ‘q’, ‘x’, ‘y’, and ‘z’, since they are not generally used in writing Raga anyway. Most of these letters exhibit left-right symmetry, making them easier to write in reverse, facilitating the boustrophedon writing direction in some Avoiuli texts.

Numbers do not seem to be written in a single stroke, looking from the relatively angular forms of characters from ‘0’ to ‘5’. Perhaps you just might encounter these numbers in the currency the Turaga nation plans to roll out, to much controversy within Vanuatu.

While the Turaga indigenous movement has been kind of obscure to the wider audience, even declining in the face of modernisation, Avoiuli still thrives amongst the Raga speakers and beyond on Pentecost Island. This writing system is still taught in a school in the village of Lavatmanggemu for a fee not paid in dollars and cents, but rather, pig’s tusks and mats, according to the Atlas of Endangered Alphabets. Travel around Pentecost Island and you might just encounter texts in Avoiuli, be it on financial records, posters, signs, or even stone carvings.