The Caribbean is known for their tropical islands and beautiful beaches. That is, if you ask anyone what comes to their mind first when the Caribbean is mentioned. But explore the right places and you just would be right. The main languages we see spoken in the Caribbean Islands today are pretty much one of the three: Spanish, English, or French, or some sort of variety, creole, or patois of those languages.

I have explored Haitian Creole some time ago, but I have always wondered about the languages spoken in the Caribbean prior to European contact. As with many people groups in the Americas, their populations have suffered drastic declines due to disease, conflict, and exploitation. And as these people groups die out, or marry with the European colonisers, so to would their languages die out, or be replaced by whatever language the European colonisers brought along with them. So today, I want to begin my exploration of the languages once spoken in the Caribbean with the most widely-spoken language in the region. It is also the language that gave Haiti, and possibly Jamaica, their names. This is the Taíno language.

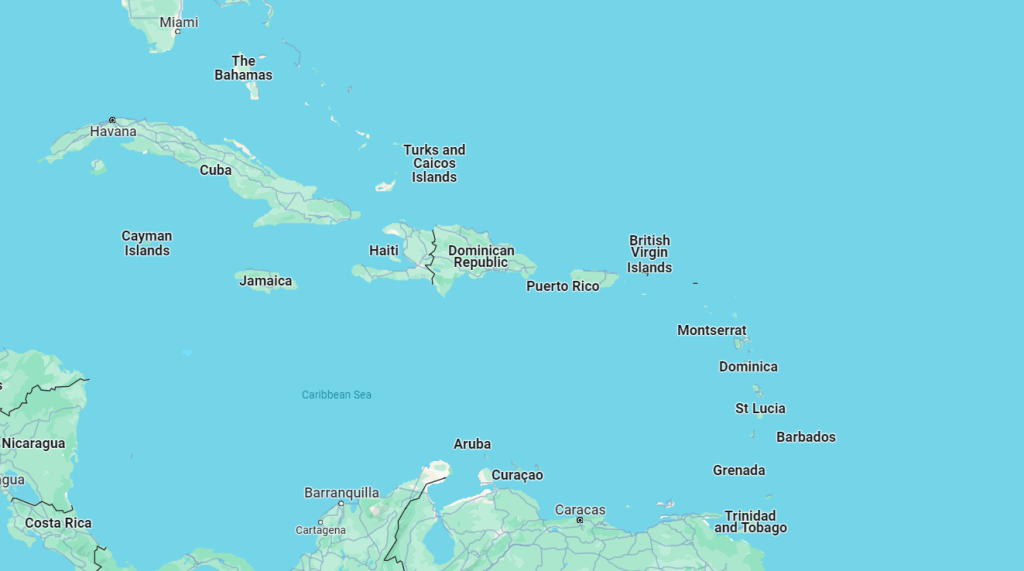

The Taíno language was once spoken as far west as Cuba and as far east as the northern Lesser Antilles, and as north as the Bahamas, and as far south as Jamaica. It is classified as a Northern Arawakan language, making it genealogically related to some indigenous languages spoken in the Guyanese shield such as Wayuu and Parauhano.

There are two subdivisions of Taíno proposed, the Classical Taíno, and the Ciboney Taíno. The former was spoken in most of Hispaniola and Puerto Rico, as well as some islands in the Lesser Antilles, while the latter was spoken in Cuba, the Bahamas, Jamaica, and western Hispaniola. At its peak, there could have been hundreds of thousands of native speakers of Taíno, even displacing other languages spoken in the region.

But with European contact, specifically the Spanish colonisers, the indigenous Taíno populations dwindled, and so too did their language. The exact year in which the Taíno language went extinct is not really known; it could be anywhere between the 16th century and the 19th century, with some proposing that Taíno may have survived longer in more isolated communities which did not see European contact until relatively recently.

However, some Taíno words have made their way into Spanish and English, just as how some Spanish words made their way into Taíno. This includes words such as “hurricane”, derived from hurakán “God of the storm”, and “mangrove”. Other words may have entered Spanish and English from other Arawakan languages, which could have shared similar words with Taíno.

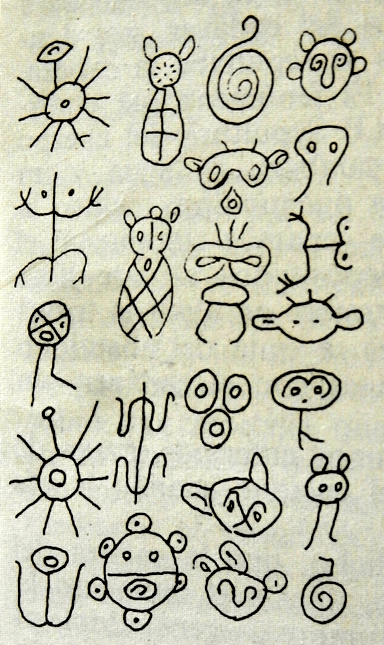

With no recordings, and Taíno leaving behind no comprehensive written record, Taíno has quite a poor record of documentation. However, what the Taíno did leave behind is a rich system of petroglyphs. These appear to represent tangible objects or deities, but the general consensus is, these glyphs do not constitute a writing system. Another mystery surrounding them is who used those petroglyphs. A leading theory is, given the feature of deities in this glyph system, Taíno shamans or priests may have played a significant role in devising these characters. However, it is also unclear exactly how many glyphs there are, although a few dozen to perhaps a few hundred may have been identified.

Without a complete writing system, what we know about the Taíno language was first recorded in writing by Spanish colonisers. As such, many Taíno words used back then were written using 15-16th-century Spanish transliteration conventions, which represented sounds like /h/ using multiple possible letters, like ‘h’, ‘j’, ‘g’, and ‘x’. Sometimes, the letter ‘x’ may have represented the /h/, /s/, or /ʃ/ sounds depending on who transcribed them. From these reconstructions, there might have been 6 vowels, and 12 consonants, with 2 nasal vowels being rarely used. However, what could be inferred is, consonant clusters do not seem to be allowed in Taíno.

Our knowledge about Taíno grammar is rather poor. There are several suffixes that have been reconstructed, serving grammatical functions such as verb agreement and possession. A system of grammatical gender was also proposed, with masculine gender taking the suffix -e, and feminine gender not taking any suffix.

Despite its poorly attested grammar, there are several language revival efforts for Taíno, some of which have new writing systems to write them. One of these reconstructed variants of the language is called Tainonaíki, a version of Taíno that has been modernised to suit 21st-century use, as well as having grammars drawing from other Arawakan languages like Arawak and Wayuu. With it, came a new alphabet, created by a Puerto Rican linguist named Javier A. Hernández. Another project of note is Hiwatahia Hekexi Taíno by the Lead Cacike Jorge Baracutay Estevez, with around 200 speakers for that particular dialect in the Higuayagua tribe.

The common pattern amongst these reconstructed Taíno languages is, they tend to make up for the lack of attested grammar in Taíno by synthesising together the various grammars of related Arawakan languages. Some new words that would have been lexical gaps in Classical or Ciboney Taíno would also have borrowings from other Arawakan languages. For instance, in Hiwatahia Hekexi Taíno, verbs and nouns from Wayuu, Wapishana, Tariana, Garifuna, Baniwa, and Añu Paraujana were used. Together, these reconstructions of the language could be used to adapt Taíno to the 21st century, and facilitate the respective language revitalisation movements in the various Taíno tribes. Perhaps we might dive into some examples of Taíno reconstructions at some point in the future, and perhaps make some comparisons in grammatical features and words the reconstructions have borrowed.

While the original Taíno language has been extinct since the 1800s, with these new efforts to try to revitalise the language, there is some new found optimism and confidence that the death of these languages have, in a way, birthed the reconstruction and creation of new ones. In some form, this is the rebirth of the Taíno people, and the language they have long lost.