In some of the past journal club essays, we have looked at the underlying environmental factors that could influence linguistic diversity of a region, or certain characteristics of languages like tones and sonority. But to claim that certain diseases do impact the characteristics of a certain group of languages seems a bit farfetched. Recently, I have come across a 2006 publication by the linguist Andrew Butcher that made such a claim — that there could be an association between otitis media and the phonological inventories of indigenous Australian languages.

This topic seems rather relevant to what I do, and what I have been doing. With a background in ecology and epidemiology, and having dabbled in linguistics on the side, the research question Butcher aimed to answer straddled the disciplines of Aboriginal Australian linguistics and the epidemiology of this disease called otitis media (OM). As such, I think that it would be appropriate to approach this proposition by Butcher from two angles — that of the prevalence of OM in the Aboriginal Australian population, perhaps making comparisons with the OM prevalence in other populations, such as indigenous populations of different geographical areas, and Australians of European descent or White Australians. The other angle would be the absence of certain sounds in the Australian languages, making comparisons with the sound systems used by other languages.

So today, as a rather lengthy preamble, I want to look into the epidemiology of OM, and try to dissect the various prevalence studies conducted for children or youths in indigenous communities. This involves examining various study designs used in prevalence studies, and systematic reviews to get a comprehensive synthesis of the available information of what the prevalence of OM is.

What is otitis media (OM)?

For people familiar with how medical terminology works, it should seem straightforward. But let us break the phrase down anyway. Otitis is of Ancient Greek origin, which can be broken down into οὖς (oûs), or its genitive form ὠτός (otos), meaning “ear” and “of the ear” respectively, and the suffix -itis, indicating that the condition described is an inflammation. Media, on the other hand, is of Latin origin, one of the word forms of the base word medius, meaning “middle”. Putting these together, we see that Otitis Media means the “inflammation of the middle ear”. This may also be defined as the infection of the middle ear, as bacteria and viruses generally cause such a disease when they infect the middle ear.

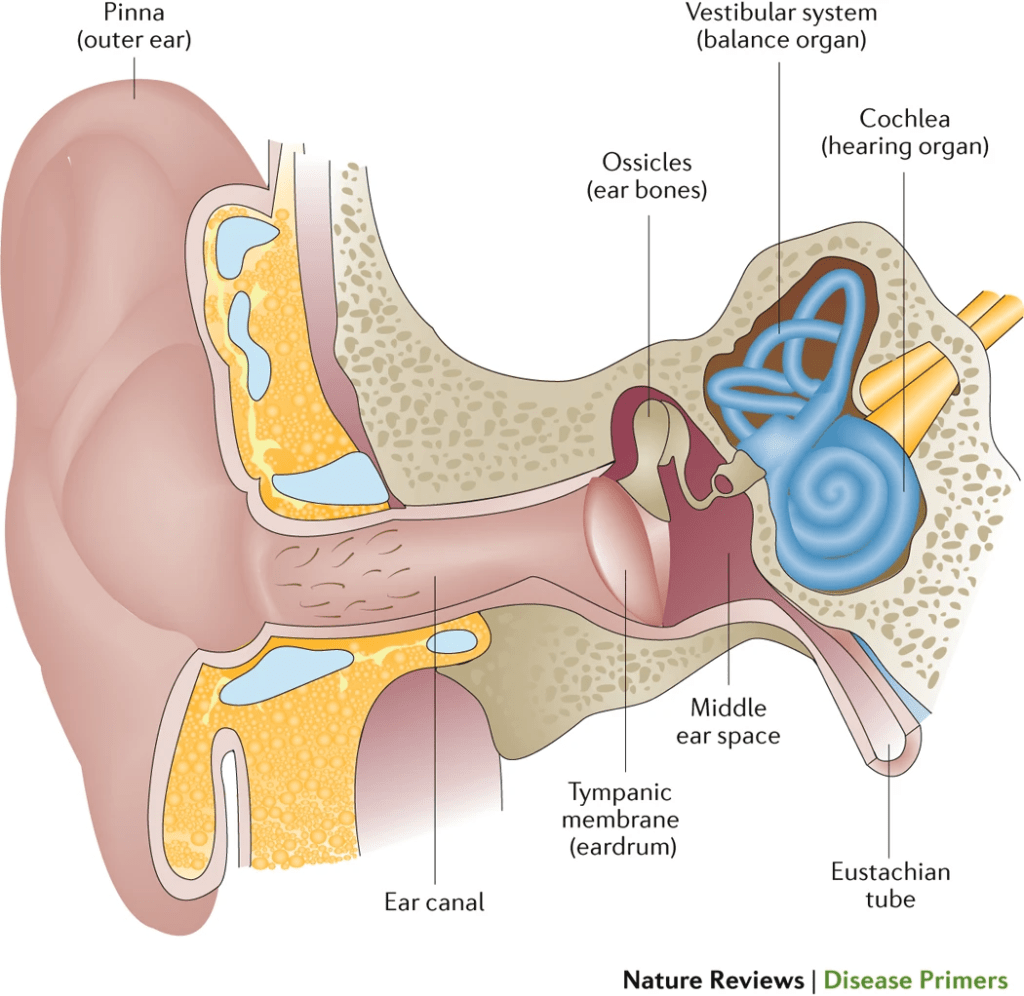

The middle ear primarily encompasses the space called the middle ear cavity, which contains the ear bones (you know, the hammer, anvil, and stirrup or the malleus, incus, and stapes respectively). This cavity is separated from the outer ear by the eardrum, scientifically known as the tympanic membrane. To visualise this, refer to the figure by Schilder et al. (2016):

There are several types of otitis media, with their own defined set of signs and symptoms clinicians or physicians would assess for. The first type is acute otitis media (AOM). If there are at least 3 episodes of AOM in the last 6 months, or 4 episodes of AOM in the last 12 months and at least one episode occurring in the last 6 months, this type of AOM could be said to be recurrent AOM. AOM typically presents itself as a rapid onset of ear pain, which indicates an acute infection. This pain is largely due to the fluid buildup (effusion) in the middle ear, exerting pressure on the eardrum. As it is incredibly discomforting, younger children tend to express this pain through different behaviours, including tugging the affected ear, excessive crying from pain, and abnormal sleep patterns, possibly to deal with the pain occurring in the middle ear.

The next type is otitis media with effusion (OME). This refers to the presence of fluid buildup in the middle ear, behind the eardrum, but without the acute onset of symptoms as one would expect in AOM (rapid onset of ear pain). It could occur as a complication of AOM, after the inflammation has largely subsided, or through a viral infection. The main symptom, according to Schilder et al. (2016), is conductive hearing loss due to fluid buildup in the middle ear. The authors also noted the close relationship between AOM and OME, where OME may persist after an AOM episode.

And lastly, there is chronic suppurative otitis media (CSOM). Unlike AOM, CSOM is a chronic condition, meaning that it is persistent, or may recur consistently. The primary symptom of CSOM is the recurrent or persistent discharge of fluid from the middle ear, which can occur through a perforated eardrum. With such recurrence, comes conductive hearing loss, and could also lead to permanent sensorineural hearing loss, that is, hearing loss which occurs in the inner ear.

One of the most direct complications from recurrent AOM and other forms of OM is the rupturing of the eardrum, or tympanic membrane perforation. This is usually observed using otoscopy, where a camera is inserted into the ear canal to inspect the condition of the eardrum. If left untreated or if perforation occurs in a recurrent manner, it could lead to conductive hearing loss. This presents as a more limited ability for the ear bones to transmit sound waves to the inner ear for signal processing, either through a buildup of fluid in the middle ear cavity, or eardrum rupturing. Such hearing loss acquired during childhood or infancy could affect language abilities and speech, as there would be a more limited range of sounds the affected individuals can reliably perceive and distinguish.

Looking at the prevalence of OM by types, we see that Butcher has cited that the prevalence of OME is over 50% in Aboriginal Australian infants, with anywhere from 50-70% of children developing some form of partial hearing loss, often resulting in the constriction of the perceptible frequency range. At first glance, this claim seems bizarrely high. While there are certainly risk factors underlying OM in general, to remark that a majority of Aboriginal Australian children have had some form of OM and its complications is a claim that I would want to try my best to verify for myself.

Assessing prevalence

In epidemiology, prevalence is defined as the “proportion of a population who have a given health outcome of interest in a certain period of time”. Simple calculations may express this as such:

Prevalence = (no. people in sample with health outcome) / (total no. people in the sample)

But there are different kinds of prevalence that epidemiologists may want to assess, depending on the study design used. This first expression may be used for cross-sectional studies, which assess a population of interest in a certain point in time. This prevalence may be referred to here as a point prevalence.

There are also studies that analyse a population over a given period of time. Prospective cohort studies, for example, could assess a given sample for a health outcome of interest over a period of 12 months. The prevalence derived from such a study design could be said to be a period prevalence. And when assessed over the course of a lifetime in the people included in the sample, this prevalence would be called the lifetime prevalence. Sometimes, you would encounter prevalence being reported as [number] per 100,000 person-years, as this could take into account the duration with which a person sampled would live with a certain health outcome assessed.

Other calculations for prevalence may also take into account the incidence of a health outcome. That is, the rate of new cases / events over a defined period of time in a population at risk. When taking into account the duration people spend living with a certain health outcome, the prevalence may be calculated as such:

Prevalence = (Incidence) x (disease duration)

In pretty much every epidemiological study, all of these reported statistics are done so using a 95% confidence interval. To put it simply, if we did 100 studies on the same population, drawing random samples from that population for each study, and computing a 95% confidence interval for each sample, then around 95 of these confidence intervals will contain the true value, here being the true prevalence of OM. With this in mind, let us look at some examples of studies assessing the prevalence of OM in indigenous people.

Individual studies

Many of the studies I have found which focus on prevalence or incidence rates (particularly for AOM) were cross-sectional in design, usually representing a snapshot of the state of OM in a studied population in a given point in time. Nonetheless, this has provided me some figures to work with to get an overview of the prevalence of OM in indigenous communities, with a focus on Aboriginal Australian children. Some of these studies did not report a confidence interval, which might be a concern when one wants to conduct a synthesis of these studies, which we will cover later.

Longitudinal studies, basically studies that assess a sample for a longer period of time, tend to be smaller scale and have fewer participants than their cross-sectional counterparts. This is mostly due to the logistics involved, and that participants, or more appropriately here, the parents of the participants, may withdraw from the study and might not be followed up with. For instance, Boswell and Nienhuys conducted two longitudinal studies in Northern Territory published in 1995 and 1996, with the 1996 study following the first year of life, and the 1995 one studying infants from birth to 8 weeks. In each study, the researchers had a small sample size, consisting of 22 indigenous and 10 non-indigenous Australian children in the 1995 study, and 36 indigenous and 10 non-indigenous Australian children in the 1996 study. Nevertheless, the main findings were, OM was more prevalent amongst indigenous Australian children than their non-indigenous counterparts, with the former also generally experiencing a more severe form of the disease.

Cross-sectional studies usually assess a larger number of participants, perhaps attributable to the easier logistics, and burden onto the participants when conducting such a study. This is where we encounter this cross-sectional study conducted by Morris et al. (2005) on Aboriginal Australian children in remote Northern and Central Australian communities. Here, the authors assessed children aged 6-30 months across 29 communities (n=709) for OM using otoscopy methods and tympanometry (the acoustic evaluation of the eardrum). And this is where they made a deeply concerning finding. Out of the 709 children assessed, they reported that the prevalence of any OM was 90% (95% CI: 88-94%), and only 8% (95% CI: 5-10%) had two normal middle ears.

This was also followed up by reporting that 43% of the children assessed had a history of eardrum perforation, and 24% of the children assessed had a perforation when the study was conducted. There was some variation between communities noted, although the reported figures for the different types of OM did not distinguish by region.

| Study | Location | Sample | Reported Figures (95% CI) |

| Boswell and Nienhuys (1995) | Northern Territory, Australia | Infants aged 0-8 weeks, Aboriginal Australian children (AAC, n=22), non-Aboriginal Australian children (nAAC, n=10) | At 15-56 days: OME/AOM, AAC: 76% OME, nAAC: 18% AOM, nAAC: 0% |

| Boswell and Nienhuys (1996) | Northern Territory, Australia | Infants aged 0-1 year, Aboriginal Australian children (AAC, n=36), non-Aboriginal Australian children (nAAC, n=10) | OME/AOM + perforation, AAC: 96% OME/AOM, nAAC: 10% normal ears, nAAC: 90% |

| Moran et al. (1979) NTEHP (1980) | Rural Australia, nationwide | Children aged 0-9yrs, Aboriginal Australian children (AAC, n=21 988), non-Aboriginal Australian children (nAAC, n=15 450) | OM, AAC: 16.6% OM, AAC, one ear: 10.7% OM, AAC, both ears: 5.9% Perforation, AAC: 15.4% OM, nAAC: 1.3% OM, nAAC, one ear: 1.1% OM, nAAC, both ears: 0.17% Perforation, nAAC: 0.7% |

| Morris et al. (2005) | Northern, Central Australia | Aboriginal Australian Children aged 6-30mths (n=709) | Any OM: 91% (88, 94) AOM no perforation: 26% (23, 30) AOM with perforation: 7% (4, 9) OME one ear: 10% (8, 12) OME both ears: 31% (27, 34) CSOM: 15% (11, 19) Dry perforation: 2% (1, 3) Any perforation: 24% (19, 29) |

| Paterson et al. (2006) | New Zealand | Pacific Children aged 2 years (n=1001) | OME/AOM: 26.9% OME: 25.4% AOM: 1.9% |

| Bruneau et al. (2001) | Inukjuak, Nunavik, Quebec, Canada | Inuit Children aged 2-6 years in 1987 (n=220) and 1997 (n=251) | 1987 OME: 3.3% CSOM: 9.4% Maximal eardrum scarring: 17.8% Minimal eardrum scarring: 45.6% 1997 OME: 2.8% CSOM: 10.8% Maximal eardrum scarring: 2.0% Minimal eardrum scarring: 45.4% |

| Homøe, Christensen and Bretlau (1996) | Greenland, Denmark | Greenlandic Children aged 3, 4, 5, 8 years (n=591) | Nuuk, n=325 AOM: 1.5% (0.5, 3.6) CSOM: 0.9% (0.2, 2.7) Chronic OM: 6.8% (4.3, 10.1) Middle ear effusion: 23.0% (18.3, 28.3) Sisimiut, n=266 AOM: 0.4% (0.0, 2.1) CSOM: 3.8% (1.8, 6.8) Chronic OM: 11.7% (8.1, 16.1) Middle ear effusion: 28.2% (22.4, 34.5) |

There is one study published in 1979 which also featured a comparison of OM prevalence between Aboriginal Australian children and non-Aboriginal Australian children. This took place through the National Trachoma and Eye Health Program (NTEHP) Survey, in which children aged 0-9 years old living in rural Australia were assessed. This covered 21 988 Aboriginal Australian children, and 15 450 non-Aboriginal Australian children. The main method used in diagnosis was otoscopy by a medical doctor, but no means of validation was reported, indicating that OME could very well be an underestimate.

Nonetheless, the researchers reported that the prevalence of OM (and perforation) was substantially higher in Aboriginal Australian children compared to non-Aboriginal Australian children, at 16.6% compared to 1.3%. They also noted substantial variation by geographical area, with the worst affected areas being Central and Western Australia for Aboriginal Australian children which recorded an OM prevalence of as high as 32.7% in the Red Centre in the Northern Territory, and 31.7% in the Western Desert in Western Australia. The lowest prevalence was recorded in the Torres Strait Islands, at 7.1%. Note that the authors did not report a 95% confidence interval, making it unlikely that this study could be used in a meta-analysis.

I am also interested in how the prevalence of OM is in the indigenous communities of the other regions of the world. For this, I have found studies on Greenlandic, Inuit, and Pacific Islander Children in Greenland, Canada, and New Zealand respectively, and the reported figures on AOM, OME, and CSOM were substantially lower than those reported by Morris et al. (2005). Additionally, for reference, the WHO considers a prevalence of CSOM of at least 4% to be a public health problem requiring urgent attention.

What do the systematic reviews say?

As we have seen, there are differing reported statistics for the prevalence of OM in Aboriginal Australian children and indigenous people. But how do we know which studies are reliable, or what the overall body of evidence is? This is where we would need a study that assesses the current body of evidence available, and synthesises them in a systematic manner. Such a study is called a systematic review. Sometimes, this study may be used together with a meta-analysis, which uses statistical methods to derive a statistic from the pooled data set in studies which are included in the meta-analysis. This is more or less done to estimate effect sizes, and you would find this a lot particularly for studies looking at risk factors of a given health outcome of interest.

Firstly, let us look at the systematic reviews assessing otitis media in Aboriginal Australian children. One of the first systematic reviews covering this topic is a 1998 by Morris, which highlighted 4 large-scale studies conducted in 1977, 1979, 1984, and 1992. Synthesising from these studies, Morris found that over a third of Aboriginal Australian children had some form of eardrum perforation, and noted a considerable variation in severe OM (perforation), ranging from 1% to 67%, with Central and Western Australia being the worst affected regions. Other hotspots were noted as well, including Central Sydney. But perhaps the main takeaway from this was, national data on OM, especially in Aboriginal Australian communities, are especially lacking. Monitoring and surveillance, at least for that time period, were mostly delegated to local health centres, which could demonstrate some sort of bias as some more remote communities may not have a same level of access to these centres as other communities. As such, there could have been an underreporting or underestimation of the true prevalence of OM in these communities.

There is also a 2008 systematic review conducted by Gunasekera et al., though I am unable to locate the full text; only the abstract was published, in the journal Pediatrics. Here, the authors found that the prevalence of OM was highest amongst Inuit and Aboriginal Australian people, reporting the figures of 81% and 84% respectively. However, I am unable to find further details than these figures.

A more recent systematic review on OM in Aboriginal Australian children was conducted by Jervis-Bardy, Sanchez, and Carney, and published in The Journal of Laryngology & Otology in 2014. Here, the authors looked at not only cross-sectional studies, but also longitudinal studies and large-scale survey studies as well, to build a clearer picture on the prevalence of OM in indigenous Australian children. They found that in indigenous Australian children, AOM had a prevalence of 7.1 – 12.8%, and OME/CSOM had a prevalence of 10.3 – 50.3%, with 31 – 50% of indigenous Australian children experiencing eardrum perforation. They also remarked that the situation of OM in indigenous communities has not improved since the nationwide NTEHP study conducted in the 1970s, as new data from 2012 in the Northern Territory Emergency Response Child Health Check Initiative cited a figure of 19.2% for AOM and CSOM (but not OME), well above the 4% threshold for CSOM prevalence in which the WHO considers a public health problem that requires urgent attention.

Concluding remarks

From the studies and systematic reviews we have seen, we can draw several interpretations, and several conclusions that we can work with when moving onto the linguistic side of Butcher’s claims. The first is that indigenous populations generally have a higher prevalence of some form of OM than their non-indigenous counterparts. However, even within indigenous populations, there is some notable variation in such prevalence. OM is notably most prevalent amongst Aboriginal Australian and Inuit or Greenlandic children, while not as prevalent in Pacific Islander children.

There are of course, challenges in assessing the prevalence of OM and its subtypes in the populations of interest. OME, for instance, is usually undetected, which could demonstrate an underestimation of the true prevalence of OME. Diagnosis is also done by different validated methods, which have their own sensitivity and specificity. As such, this compounds the difficulty in epidemiological studies assessing the prevalence of OM.

Additionally, we must note that the term Aboriginal Australian people is an umbrella term; it is a term used to identify the indigenous peoples of Australia, and from the studies we have looked at, these people groups are treated as one homogenous group. However, as you might have seen from the Languages of Australia series, this is not quite the case. There are hundreds of indigenous Australian people groups and languages, which can be further split into clans, moieties, skin groups, and dialects, showing how heterogeneous the indigenous Australian peoples actually are. Each group could have a different quality of life, such as access to basic hygiene, healthcare, and other kinds of means that could affect how susceptible one is to OM. This is seen in the cross-sectional study by Morris et al. (2005) for example, which reported regional variation in percentage of children assessed who have severe OM.

When applying this background to assess Butcher’s hypothesis, we must also note that these studies only look at the contemporary prevalence of OM, while languages tend to evolve over the course of generations. As such, to properly ascertain if there is indeed a correlation between OM prevalence and Aboriginal Australian language sound systems, one would need to look into the history of the disease in pre-colonial Australia as well. This is, understandably, incredibly difficult to do so, given the different understanding of medicine and health back then, and the lack of accessible documentation prior to European contact. Thus, it would also be difficult to ascertain if OM infections were an introduced disease due to European contact, or if such infections were already prevalent prior.

Nonetheless, the reported statistics in these studies I have found send a rather concerning message. Otitis media is still a public health problem especially amongst Australia’s indigenous communities, with its prevalence generally reported well above indigenous communities in other regions of the world, and the threshold for which the WHO considers a problem requiring urgent attention (for CSOM). Numerous studies have also been published studying the risk factors behind OM, and why indigenous communities generally have higher prevalence than their non-indigenous counterparts, raising suggestions on how this public health problem may be tackled. I hope that today’s essay has shed light on the epidemiology of otitis media as a whole, and built a comprehensive epidemiological background on what Butcher sets out to claim. In the next part of this investigation, I want to dive deeper into the phonologies of indigenous Australian languages, and the arguments for and against the purported role of otitis media in influencing these phonologies.

Further Reading

Butcher’s claims that inspired today’s essay:

Butcher, A. R. (2006) ‘Australian Aboriginal languages: Consonant salient phonologies and the ’place-of-articulation’ imperative’, in Harrington, J., & Tabain, M. (Eds.). Speech Production: Models, Phonetic Processes, and Techniques (1st ed.). Psychology Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203782989.

Butcher, A. R. (2019) ‘The special nature of Australian phonologies: Why auditory constraints on human language sound systems are not universal’, Proceedings of Meetings on Acoustics, 35(1), pp. 060004.

Otitis media and its subtypes:

Klein, J. O. (1994) ‘Otitis media’, Clinical Infectious Diseases, 19(5), pp. 823-832. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4458141.

Lieberthal, A. S., Carroll, A. E., Chonmaitree, T., Ganiats, T. G., Hoberman, A., Jackson, M. A., Joffe, M. D., Miller, D. T., Rosenfeld, R. M., Sevilla, X. D., Schwartz, R. H., Thomas, P. A. and Tunkel, D. E. (2013) ‘The Diagnosis and Management of Acute Otitis Media’, Pediatrics, 131(3), pp. e964-e999.

Schilder, A. G. M., Chonmaitree, T., Cripps, A. W., Rosenfeld, R. M., Casselbrant, M. L., Haggard, M. P. and Venekamp, R. P. (2016) ‘Otitis media’, Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 2(1), pp. 16063.

Epidemiological terms:

Borges Migliavaca, C., Stein, C., Colpani, V., Barker, T. H., Munn, Z., Falavigna, M. and on behalf of the Prevalence Estimates Reviews – Systematic Review Methodology, G. (2020) ‘How are systematic reviews of prevalence conducted? A methodological study’, BMC Medical Research Methodology, 20(1), pp. 96.

Kier, K. L. (2011) ‘Biostatistical applications in epidemiology’, Pharmacotherapy, 31(1), pp. 9-22.

McKenna, S. L. and Dohoo, I. R. (2006) ‘Using and interpreting diagnostic tests’, Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract, 22(1), pp. 195-205.

Rothman, K. J. (2012). Epidemiology: An Introduction. Oxford University Press, pp. 53. ISBN 978-0-19-975455-7.

Whiting, P. F., Davenport, C., Jameson, C., Burke, M., Sterne, J. A., Hyde, C. and Ben-Shlomo, Y. (2015) ‘How well do health professionals interpret diagnostic information? A systematic review’, BMJ Open, 5(7), pp. e008155.

Epidemiological studies:

Boswell, J. B. and Nienhuys, T. G. (1995) ‘Onset of Otitis Media in the First Eight Weeks of Life in Aboriginal and Non-Aboriginal Australian Infants’, Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology, 104(7), pp. 542-549.

Boswell, J. B. and Nienhuys, T. G. (1996) ‘Patterns of Persistent Otitis Media in the First Year of Life in Aboriginal and Non-Aboriginal Infants’, Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology, 105(11), pp. 893-900.

Bruneau, S., Ayukawa, H., Proulx, J. F., Baxter, J. D. and Kost, K. (2001) ‘Longitudinal observations (1987-1997) on the prevalence of middle ear disease and associated risk factors among Inuit children of Inukjuak, Nunavik, Quebec, Canada’, Int J Circumpolar Health, 60(4), pp. 632-9.

Homøe, P., Christensen, R. B. and Bretlau, P. (1996) ‘Prevalence of otitis media in a survey of 591 unselected Greenlandic children’, International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 36(3), pp. 215-230.

Moran, D. J., Waterford, J. E., Hollows, F. and Jones, D. L. (1979) ‘Ear disease in rural Australia’, Medical Journal of Australia, 2(4), pp. 210-212.

Morris, P. S., Leach, A. J., Silberberg, P., Mellon, G., Wilson, C., Hamilton, E. and Beissbarth, J. (2005) ‘Otitis media in young Aboriginal children from remote communities in Northern and Central Australia: a cross-sectional survey’, BMC Pediatrics, 5(1), pp. 27.

Paterson, J. E., Carter, S., Wallace, J., Ahmad, Z., Garrett, N. and Silva, P. A. (2006) ‘Pacific Islands families study: The prevalence of chronic middle ear disease in 2-year-old Pacific children living in New Zealand’, International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 70(10), pp. 1771-1778.

The Royal Australian College of Ophthalmologists. (1980) ‘The National Trachoma and Eye Health Program’. Promail Printing Group, Sydney.

World Health Organisation. (2004) ‘Chronic suppurative otitis media – Burden of illness and management options’. World Health Organisation, Geneva.

Systematic reviews:

Coleman, A., Wood, A., Bialasiewicz, S., Ware, R. S., Marsh, R. L. and Cervin, A. (2018) ‘The unsolved problem of otitis media in indigenous populations: a systematic review of upper respiratory and middle ear microbiology in indigenous children with otitis media’, Microbiome, 6(1), pp. 199.

Gunasekera, H., Haysom, L., Morris, P. and Craig, J. (2008) ‘The global burden of childhood otitis media and hearing impairment: A systematic review’, Pediatrics, 121(Supplement_2), pp. S107-S107.

Jervis-Bardy, J., Sanchez, L. and Carney, A.S. (2014) ‘Otitis media in Indigenous Australian children: review of epidemiology and risk factors’, The Journal of Laryngology & Otology, 128(S1), pp. S16–S27. doi:10.1017/S0022215113003083.

Morris, P. S. (1998) ‘A systematic review of clinical research addressing the prevalence, aetiology, diagnosis, prognosis and therapy of otitis media in Australian Aboriginal children’, Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 34, pp. 487-497. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1754.1998.00299.x.