When doing my research and reading up for this essay published some time ago, I came across this article that particularly caught my attention. You might have noticed it in the Further Reading section at the end of the essay as well. And so, I decided to take a thorough read of the article, and yeah, welcome to a new essay of The Journal Club. Today, we will look at a publication by Russell Barlow, published in the journal Diachronica in 2023 titled “Papuan-Austronesian contact and the spread of numeral systems in Melanesia”.

This article largely focuses on the use of number systems in Austronesian and Papuan languages, taking particular note of the Austronesian quinary systems, or base-5 number systems. After all, many Austronesian languages we know of use a decimal system, with unique number terms for “six” to “nine”. But among the hundreds of Austronesian languages there are in the world, there are around 200 – 300 of them that have quinary number systems instead, with compounded words for “six” through “nine” such as “five-one”. Some of them have unique words for “ten”, and for those languages, we would say those are bi-quinary number systems.

As we have covered previously, languages in New Guinea adopt many different forms of expressing numerals, from body-part tally systems to a whole host of unconventional number bases like the senary. With Austronesian and Papuan languages spoken in New Guinea, some have suggested that the Papuan languages have influenced, in some part, the number systems in the Austronesian languages. But this study argued otherwise — that the Austronesian languages influenced some of the Papuan languages to adopt a quinary numeral system, while the Austronesian languages on New Guinea developed the quinary numeral system influenced by the digit-tallying cultures there.

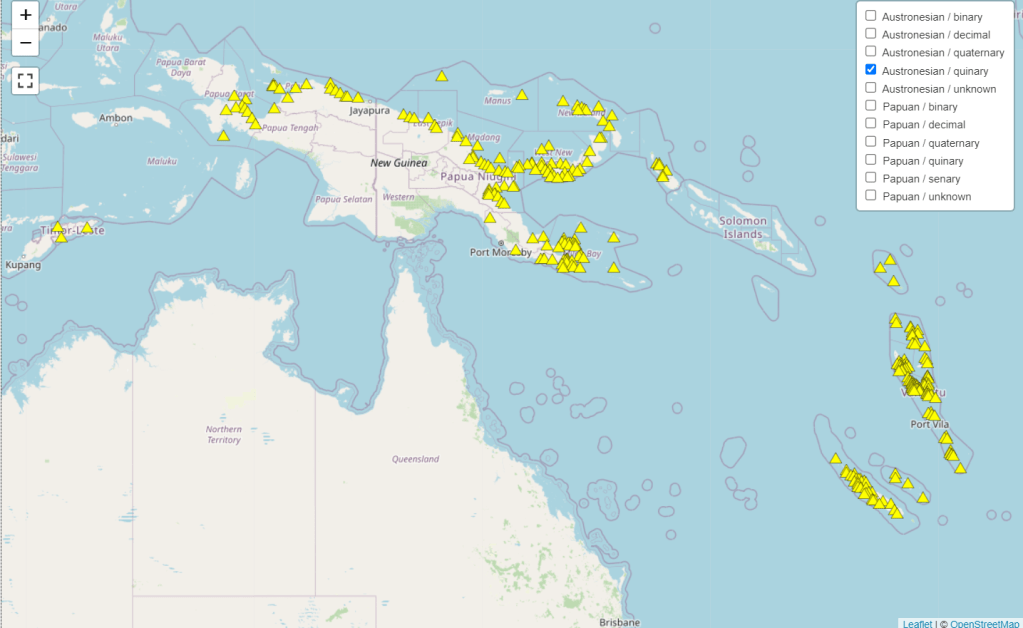

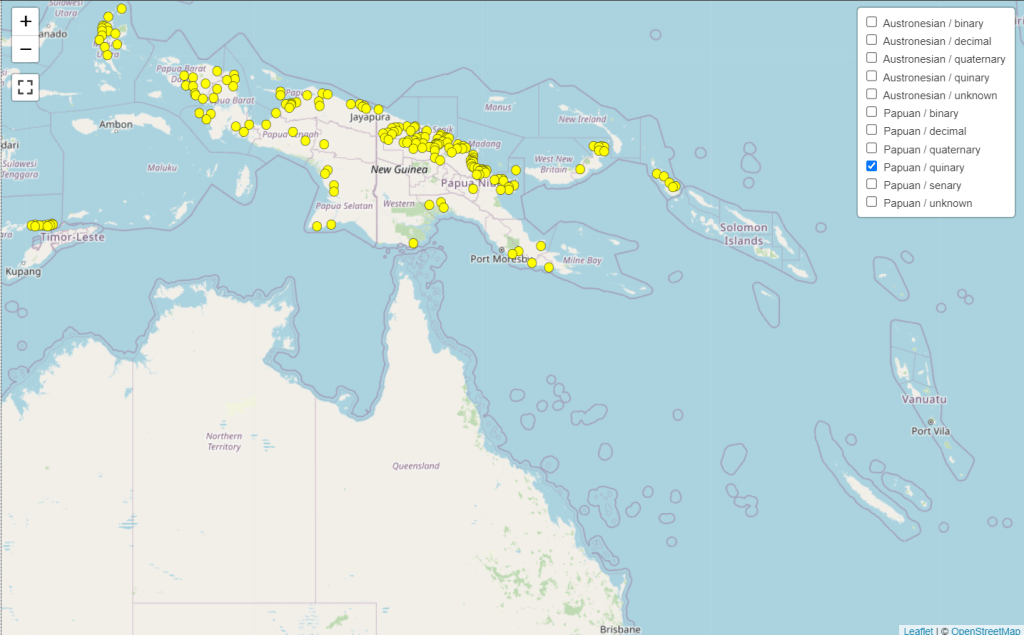

To get a visualisation of what the study is dealing with, I looked up a map in the supplementary information visualising the geographical distribution of Austronesian languages that use the quinary number system. The distribution was quite interesting. In Barlow’s data set, among the couple hundred or so of Austronesian languages that use the quinary number system, all of them, with the exception of four extant languages and one extinct one, are clustered in the region of Melanesia, which encompasses countries like Papua New Guinea, Indonesia (Papua province), Vanuatu, and New Caledonia (part of Overseas France). Furthermore, on New Guinea, the Austronesian languages that use the quinary are spoken in more coastal settlements. This pattern is also seen in Austronesian languages that use the quaternary (base-4), and the binary (base-2), probably with the exception of those in Morobe province in Papua New Guinea. You can access the supplementary information here.

The Duwet language in the Austronesian languages, for example, has lost most of its number terms, adopting a binary numeral system instead, with an additional word for 5. Compare and contrast the numerals from 1 to 10 for Maori (decimal) and Duwet below:

| Maori | Duwet | |

| 1 | tahi | ta(ginei) |

| 2 | rua | seik |

| 3 | toru | seik ba ta |

| 4 | whā | seik ba seik |

| 5 | rima | limangga arinang (literally hand-half) |

| 6 | ono | limangga arinang anau na ta (literally hand half, another one) |

| 7 | whitu | limangga arinang anau na seik |

| 8 | waru | limangga arinang anau na seik ba ta |

| 9 | iwa | limangga arinang anau na seik ba seik |

| 10 | tekau | limang seik (literally hands two) |

Barlow classified 1190 Austronesian languages and 635 Papuan languages by the type of number system each one uses, further subgrouping them by geographical area (like in and out of the New Guinea mainland).

| Numeral system | Austronesian in Melanesia | Austronesian outside Melanesia | Total Austronesian |

| Binary | 36 | 0 | 36 |

| Decimal | 176 | 683 | 859 |

| Quinary | 285 | 5 | 290 |

| Uncommon | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| Total | 502 | 688 | 1190 |

| Numeral system | Papuan in New Guinea | Papuan outside New Guinea | Total Papuan |

| Binary | 397 | 5 | 402 |

| Decimal | 8 | 26 | 34 |

| Quinary | 137 | 42 | 179 |

| Uncommon | 17 | 3 | 20 |

| Total | 559 | 76 | 635 |

There were not really much statistical stuff used in the study, other than these descriptive statistics that show how many Austronesian and Papuan languages use which number systems. However, what was extensively discussed were the possible ways these languages have interacted with one another to produce the pattern we see today. The bulk of this investigation focused on the reconstruction of certain number terms in the proto-versions of certain languages, their language families, or part thereof. So, from the tables and the maps, what could explain the distribution of quinary number systems in the Austronesian and Papuan languages in Melanesia?

Barlow’s explanation is, if quinary number systems existed in the Papuan languages of New Guinea before the Austronesians arrived there, then we should be able to reconstruct the number terms “three” and “four” from the respective language families involved. There is pretty much an agreed upon set of Proto-Oceanic and Proto-Austronesian reconstructions of the number terms from “one” to “nine”, which are unique and simplex forms. This suggests that the common ancestor of the Austronesian languages most likely used a decimal number system, a far cry from the phenomenon we see in the 200 or so Austronesian languages in Melanesia.

To do this, Barlow tried to reconstruct number terms for “three” and “four” for the larger language families, arguing that smaller language families and language isolates would present immense difficulty or uncertainty in reconstructing these number terms as they were prior to Austronesian contact. This narrowed his reconstructions down to 20 larger language families classified as Papuan languages, defined as a taxonomic grouping of more than 10 daughter languages.

Among the larger Papuan language families, Barlow did not manage to get reconstructions of “three” and “four”, although some promising results were found for the Ndu family, in which multiple reconstructions are likely for the numbers “three” and “four”. Similarly, the East Cenderawasih Bay language family seems appears to potentially have reconstructions for “three” and “four”, but not “two”. However, due to the scarcity of studies covering that language family, Barlow remarked that more research would be needed to elucidate the potential for such number terms to be reconstructed.

He also went on to investigate some of the smaller Papuan language families, where he found a similar pattern of a stark lack of reconstructions for the terms “three” and “four”. Perhaps the most significant exception was the South Bougainville languages, where “three” and “four” could be reconstructed as *be- and *kↄre respectively. Barlow also notes for a majority of the Papuan languages using the decimal or quinary systems, there has been borrowing from Austronesian languages, or some sort of calquing.

While this explains the pattern of quinary number systems in the Papuan languages of New Guinea, how would these explain the loss of decimal systems in the Austronesian languages upon contact with the Papuan languages?

As Barlow put it, there are two suggested predominant processes at hand here. Firstly, the influence of digit tallying systems in the Papuan languages. He posits that the Papuan languages the Austronesian cultures first encountered tended to have no number terms above “two” or “three”, and they have a culture of digit tallying using their hands and feet. It was this tallying system that the Austronesian cultures, and later, languages adopted. This is supported by the use of “person” or “man” to refer to the number 20 in some Austronesian languages in Melanesia, wherein all the digits of a single person have been tallied.

This digit tallying system may have initially been used concurrently with the decimal counting system in the Austronesian languages, but the decimal system slowly shifted to being used in more formal contexts such as feasts. With the erosion and loss of the decimal number system in everyday speech, as Austronesian languages incorporate digit tallying instead, so too did the use of numbers “six” through “nine” decline, and later, disappear. With increasing reliance on digit tallying, a quinary number system would have been favoured, and conventionalised in the Austronesian languages in Melanesia over time. However, it must be noted that this loss of a decimal system in favour of a quinary one was more of a cultural process rather than linguistic.

The other proposed process at play alludes to the fact that the Papuan term is not a monolithic cultural category. Barlow posits that there are Papuan languages that already use, or have independently innovated a quinary number system prior to Austronesian contact, and the strongest evidence for this occurs in the western regions of New Guinea, like Cenderawasih Bay. This region also happens to be the theorised place where Austronesians would have migrated to first during their expansion into Melanesia. However, this hinges on the condition that the Austronesians that first reached New Guinea would have familiarised themselves with the digit tallying systems in order for some sort of linguistic calquing to occur.

Acknowledging the role of digit tallying cultures, and that the Papuan languages are not a monolithic cultural category, Barlow was able to propose a possible narrative of what possibly went down when the Papuan languages interacted with the Austronesian languages upon contact.

During the Lapita expansion, when Austronesian people groups migrated into Melanesia around 3500 years ago, they brought with them their own systems of digit tallying, while spreading their number systems into the Papuan languages, which mostly have their own binary number systems, and their own systems of digit tallying. However, many of these Austronesian languages would be influenced by the Papuan languages and cultural norms as well, leading to the loss of their decimal numeral systems. When this loss occurred remains to be studied. As migration progressed, the Austronesian cultures arriving in other parts of Melanesia like Vanuatu and New Caledonia would already have their own quinary number systems upon arrival, possibly explaining why these number systems still use the quinary despite not seeming to have come in direct contact with Papuan languages.

However, there are some glaring caveats to the study, which he also noted. These reconstructions are based off our current knowledge of historical changes in the Papuan languages, and the Papuan languages are notoriously under-documented. This scarcity of documentation, like in the East Cenderawasih Bay languages, would give us less information to work with to hypothesise the possible sound changes that would have occurred over time. Given that we are extrapolating these sound changes over quite a long time, a lack of documentation would mean that we cannot reliably reconstruct certain words in these languages. Perhaps if linguists or anthropologists study these languages more profoundly, we could get a better idea about the history of these languages, and possibly build reconstructions of their number terms. Who knows, perhaps our current preconceptions of number systems in the Papuan languages could be proven outdated. But this would entail further research far beyond just the word lists one would find on Glottolog.

The second albeit more minor caveat is, quinary or decimal number systems can occur in Papuan languages independently, and may also arise without having contact with Austronesian languages. It could be the case where digit tallying in these languages produce monomorphemic simplex words for words like “three” and “four” over time, which may be untraceable to Austronesian roots. Does this inherently dispute the narrative Barlow is arguing for? Well, not necessarily. Linguistic features can arise in languages independently, leading to some sort of polyphyletic deal when it comes to evolution of number systems. However, linguists have largely agreed on the typological profile of number systems in the Papuan languages, that these languages usually use binary number systems, and those that independently develop other number systems without Austronesian contact are more ‘outlier’ cases.

So, what have we learned from all of this?

Barlow’s study presents an interesting counter to the preconceptions that the quinary number systems in the Austronesian languages of Melanesia are due to contact with the Papuan languages in New Guinea. Instead of what could be interpreted as a one-sided influence on the Austronesian languages by the Papuan languages, Barlow argued that this influence went both ways, but instead of the Papuan languages already having their own base-5 number system, they generally had a binary number system that eventually incorporated loanwords of Austronesian origin to make base-5. In that process, the Austronesian languages would also lose their decimal number systems in favour of the quinary through various processes. This study also visualises these cross-linguistic influences through a numeral lens. We do not really find such rich examples other than in Melanesia, especially for a lexical class thought to be so fundamental to our languages, our numbers. Reading this study was really quite interesting, and I highly recommend you check it out in full. Fortunately, this study is in open access, and so there should not be any barriers to reading this publication.

Further Reading

Barlow, R. (2023) Papuan-Austronesian contact and the spread of numeral systems in Melanesia. Diachronica, 40(3), pp. 287-340. https://doi.org/10.1075/dia.22005.bar.