The Bering Strait forms the maritime boundary between two continents, Asia and North America. Not only does the International Date Line run through it, separating the easternmost part of Russia and the westernmost part of Alaska by at least an entire day, but it also once formed the land bridge that humans theoretically used to cross into America during the last glacial maximum. Today, we will look at the languages spoken in Russia’s far east, namely, the Autonomous Chukotka Okrug.

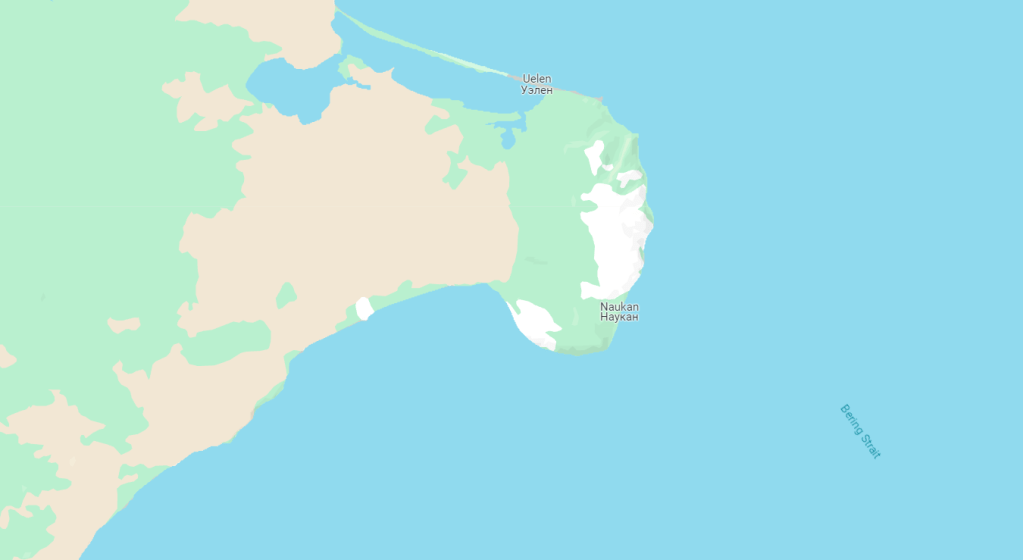

Within this Okrug, is the easternmost settlement of Asia, Uelen. It is home to around 700 people, and it inherited the title of Asia’s (and Russia’s) easternmost settlement after Naukan’s disbanding in 1958. Here in Uelen, other than Russian, we find two other languages spoken, a critically endangered language called Naukan Yupik, and a definitely endangered language called Chukchi.

Firstly, we will look at Chukchi. Within this Okrug, there are around 8000 native speakers of the language, but its use has been steadily eroded over the past several decades. Like many other languages in Russia, while children are taught both Russian and their indigenous language, speakers having been leaning towards using Russian in daily lives, leading to the decline in use of their indigenous tongue. We have seen an example of this occurring in the Sakha language as well.

Next, we have to talk about the name Chukchi. It is not a name given by the Chukchi people, that name would be called Luorawetlat or Luorawetlan, meaning “the real people” in the plural and singular respectively. The name Chukchi derives from the Russified version of a Tungusic word, likely from the Even or Evenki language, for “a man rich in reindeer”, or чавчыв or Chawchu. This alludes to the reindeer-herding traditions of the Luorawetlat, where a man’s wealth is determined by the number of reindeer he has. I am not sure if Chukchi could be interpreted as a pejorative term, but it is the word I see most often.

This language is remarked to be one of the Paleo-Siberian languages, that is, languages that have been spoken in the region before being displaced by more major language families like the Tungusic, Turkic, and ultimately, Indo-European for the case of Russian. Chukchi belongs to one of the smaller language families called Chukotko-Kamchatkan languages, and is most closely related to the Koryak language. All of these languages in the family are endangered in some form, with Kerek and Southern and Eastern Kamchadal being extinct.

As with many languages spoken in the region, Chukchi uses the Cyrillic alphabet to write today, although with a few modifications to properly represent the sounds not found in Russian, but are found in Chukchi. At a first glance of the Chukchi Cyrillic alphabet, you may notice several letters with hooks on them.

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ё ё | Ж ж |

| З з | И и | Й й | К к | Ӄ ӄ | Л л | Ԓ ԓ | М м |

| Н н | Ӈ ӈ | О о | П п | Р р | С с | Т т | У у |

| Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Щ щ | Ъ ъ | Ы ы |

| Ь ь | Э э | Ю ю | Я я | ʼ |

These are used to represent some sounds that are not found in Russian, such as /ŋ/, represented by ӈ, /q/, represented by ӄ, and arguably, /ʎ/ represented by ԓ, in contrast to /ɬ/, represented by л. Likewise, there are letters in this alphabet that represent sounds found in Russian, but not found in Chukchi. This includes voiced stop consonants like /b/ (б), which are absent in Chukchi. Chukchi also has this consonant called voiced retroflex approximant /ɻ/ written as р, a sound found in languages like Tamil (represented by ழ் in Tamil).

Perhaps an unusual characteristic of Chukchi phonology is, male and female speakers kind of use different sounds in speech, which mainly pertains to the /s/, /t͡ʃ/, and /ɻ/ sounds. Male and female dialects are unusual in this region, and I cannot find any evidence supporting these separate dialects between the sexes in its Koryak counterpart.

One reason for this separate dialect is, for female speakers, it is taboo to pronounce the names of their husband’s relatives and similar-sounding words. This could have led to certain types of avoidance speech where certain consonant sounds in the female dialect replace the taboo sounds. One example is the replacement of the /ɻ/ and /ɻk/ sounds with /ts/ or /tss/ in the female dialect, and so what is рыркы (walrus) as spoken in men is pronounced цыццы in women. This is also the case for the /t͡ʃ/ sound, and occasionally, the /s/ sound, which are pronounced as /ts/ in the female dialect.

Chukchi has a vowel harmony system, with a weird /e/ vowel situation. Its vowel harmony is based on vowel height, where high vowels go with high vowels in a word, and low vowels go with low vowels in a word. Chukchi has the vowel phonemes /i/, /u/, /e/, /o/, /a/, and the schwa /ə/. The recessive vowels are /i/ and /u/, while the dominant vowels are /o/ and /a/. This recessive-dominant system is used instead of the front-back or high-low distinctions in other languages that have vowel harmony, as recessive vowels are replaced by their dominant counterparts in some contexts in Chukchi grammar, or when there is a dominant vowel in a word otherwise populated with recessive ones.

And then we come to the vowel /e/. There are technically two types of the same vowel, although they are pronounced and realised identically. In phonetic notation, these are noted as /e1/ and /e2/, with /e1/ belonging to the recessive vowel group, and /e2/ belonging to the dominant vowel group. In fact, the only way to tell these vowels apart is how they are used in the language’s vowel harmony system.

What is more bizarre is, there is another writing system for Chukchi invented from scratch by a single individual. Almost unheard of and almost lost to time due to Soviet contact, it is thought to be the northernmost case of a language creating its own writing system and orthography, leading to a lot of linguistic interest in the evolution, development, and origins of writing systems in rather isolated contexts. This writing system is called Tenevil, after the Luorawetlan who invented it.

We are not quite sure what kind of writing system Tenevil is, but as over a thousand basic elements of this writing system have been identified thus far, the most probable theory is that Tenevil is a logographic script, much like oracle bone script used early in Chinese history. The history of Tenevil only stretches as far back as around a century ago, when Tenevil (ca. 1890 – ca. 1940) lived. Used by a few people, predominantly by his family, his writing system did not gain widespread adoption by the wider Chukchi-speaking population, preferring to use the Cyrillic alphabet instead. The most popular image showing Tenevil characters is from a 1963 edition of a book by D. Dieringer, titled Alphabet, in Russian:

Chukchi has a rather unusual grammar. While it has a relatively free word order, it tends to bias towards subject-object-verb basic word order. Furthermore, it has a rather extensive system of incorporation. This is where a compound word is formed by combining the verb or another category with a direct object or an adverb. Incorporation makes the verb more specific, but does not really specify a particular object targeted by the verb.

To illustrate this, compare the following two phrases, “with a spear” and “with a good spear”. For the former, it is га-пойг-ы-ма, while for the latter, it is га-таӈ-пойг-ы-ма. Did you spot the incorporated word?

That is right, the таӈ is the root of the Chukchi word for “good”. Its recessive counterpart is тэӈ, while its full form is ны-тэӈ-ӄин.

Incorporation is a strategy used to create complex or compound words as well, although distinguishing this from other methods of forming compound words is challenging. “Shop” (вэлытко-ран) may be formed from “trading house”, for instance. But in some cases, such compounding may be inconvenient, leading speakers to just borrowing directly from Russian instead.

Chukchi is a polysynthetic language, and incorporation is just one example of its polysynthetic features. In a way, this shares similarities with the Inuit languages, which are also famous for their polysynthetic nature. One interesting thing I found is, according to Skorik, there does not seem to be adjectives in the Chukchi language. Instead, there are predicates, which do not seem to neatly fit into traditional classifications and definitions of parts of speech.

Additionally, Chukchi follows an ergative-absolutive alignment system. This is the system where the subject of an intransitive verb (verb that does not take a direct object) behaves like the object of a transitive verb (verb that takes a direct object). Sometimes, case markers or suffixes can mark the ergative or the absolutive case on the respective words. To illustrate this using more familiar languages like Basque, consider the two following examples:

- Ben has arrived

- Ben etorri da

- Ben has seen James

- Benek James ikusi du

In the first example, Ben is the subject of a clause that has an intransitive verb. In the second example, Ben is the subject of a clause that has a transitive verb, while James is the object. Thus, in the second example, Ben is marked with a case ending called the ergative, while James carries the absolutive case, as James here is treated the same way Ben is in the first example. Such an alignment system is also seen in the Yupik and Inuit languages, which are spoken either in the Okrug, or across the Bering Strait in Alaska and Canada.

Other than these cases, sources differ on the total number of grammatical cases Chukchi has. The 1999 thesis by Michael J. Dunn mentioned 13, while Russian sources like Skorik suggest 7 to 9. This probably alludes to differences in defining which suffixes constitute a grammatical case. Dunn mentioned some unusual cases like the perlative, which indicates motion through or along something, and the orientative case, which indicates something is oriented or facing another object.

Chukchi numerals are interesting. While they are a base-20 system, this is broken down into terms for 5 (Мэтԓыӈэн), 10 (Мынгыткэн), 15 (Кыԓгынкэн), 20 (Ӄԓиккин), and 400 (Ӄԓиӄӄԓиккин). The sub-base of 5 kind of corresponds to a “hand”, suggesting some sort of digit tallying that forms the basis of Chukchi numeral terms. There are no unique terms for numbers like 7 or 8; these are compounded from smaller numbers, as 5 + 2, and 5 + 3 respectively. There is a decimal system used as well for numbers above 100, but that is largely due to Russian influence into the Chukchi language.

This brings us to the influence of other languages on Chukchi words. In modern times, there are numerous loanwords of Russian origin in the Chukchi language, as Chukotka became Russified over time. Modern things and concepts that Chukchi speakers are more recently exposed to generally have loanwords from Russian. However, there are also other languages in the region that might have some part to play in influencing the lexicon of Chukchi. It is uncertain to which extent certain languages influence the vocabulary of Chukchi, but there could be loanwords of Yupik origin, or Tungusic and Turkic origin.

Fortunately, there are resources in English dedicated to Chukchi, to get a glimpse of how the language works. One example is this page from the University of Essex, although it is an archived version of a site that does not seem to work today. Most of its captures were made in 2005 to 2006.

But if you want a more extensive coverage of the language, you would definitely want to brush up on Russian. Like other indigenous languages in the region, most resources covering the language are in Russian, and only a subset of it has an English translation. One site to use as a springboard is this one here, which has a few chapters of the reference grammar of Chukchi by Skorik. Another compilation of further resources for Chukchi can be found here, although not all of them may be readily accessible by the general public. With Chukchi use diminishing especially in younger speakers, accessible documentation of the language has to be made to ensure its preservation and revitalisation in the coming years.