When we talk about very cold places, there are four primary regions that come to mind. Antarctica, Siberia, Northern Canada, and Greenland. After all, they are places commonly associated with being very close to the poles, and have rather harsh winters. But for the coldest city in the world, we might look towards the depths of Siberia for our answer.

If you have watched travel or cultural channels, chances are, you would have come across videos like “Life in the Coldest City in the World (-57°C)” or something along those lines. Almost unanimously, the city these videos cover is Yakutsk, located in the Sakha Republic of Russia. With an annual mean temperature of -8°C, Yakutsk, with a population of around 300 000 people, is the world’s coldest major city by annual mean temperatures.

However, this might not necessarily be the coldest permanent settlement in the world. Oymyakon, also in the Sakha Republic, is home to less than a thousand people, but boasts the accolade of the world’s coldest permanent settlement. In the harsh winters of these settlements, temperatures can average around -50°C, with schools closing when the mercury hits -55°C. It is also the place where some of the coldest air temperatures in the world have been recorded, at -67.7°C but way back in 1933.

Despite this long and harsh winter climate, there are people groups who have called this place home for the past centuries or millennia. Called the Sakha people, they speak a Turkic language closely related to Dolgan, and also related to languages like Tuvan and Altai. This is Sakha, or Yakut.

The Sakha language is spoken by around half a million people, primarily in the Sakha Republic in the Russian Federation. As Sakha is taught in local school curricula, there is still transmission of the Sakha language to the younger generations. There are many resources to learn Sakha, but most of them are in Russian. So if you want to kill two birds with one stone here, pick up both Sakha and Russian!

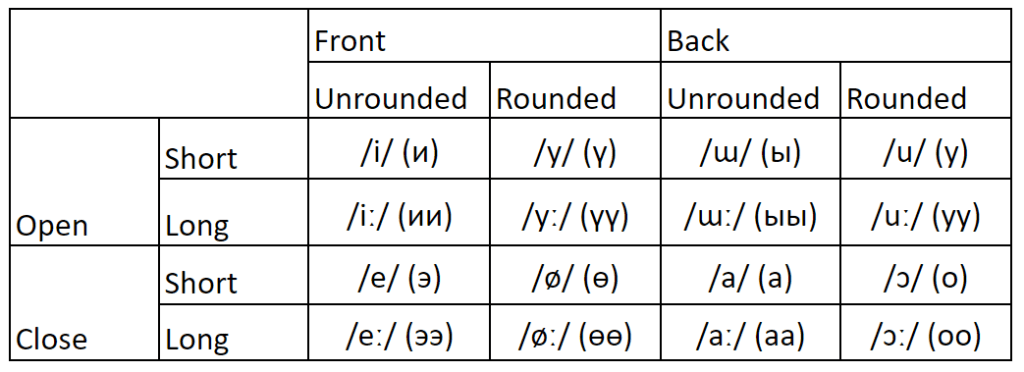

Like many Turkic languages, Sakha has a system of vowel harmony. That is, words with front vowels must be conjugated with suffixes with front vowels, and words with back vowels must be conjugated with suffixes with back vowels. And unlike some languages in the region like Mongolian, there are no ‘neutral’ vowels. In addition to front and back vowels, Sakha also distinguishes between rounded and unrounded vowels, open and closed vowels, and long and short vowels. This makes it a total of 16 vowel phonemes, plus another 4 recognised diphthongs. Sakha also takes it a step further with this vowel harmony characteristic — it also does vowel harmony by vowel rounding. In other words, rounded vowels with unrounded vowels with unrounded vowels, and rounded vowels with rounded vowels.

This harmony does not just apply to vowels; consonants undergo a similar agreement called “consonant assimilation”, where the consonant sound taken up by a suffix is affected by the sound that immediately precedes it. Such sounds include agreement for the i, u, ï, ü sounds, the a, e, o, ö sounds, the /l/, /j/, and /ɾ/ sounds, the /χ/ sound, voiceless consonants like /k/, and nasal consonants like /m/. Interestingly though, while many Turkic languages contain hushing sibilants like the /ʃ/ sound in Turkish (written as “ş“), Sakha lacks such consonants. Conversely, where many Turkic languages lack the /ɲ/ sound (you might compare this to the letter “ñ” in Spanish), Sakha has that sound, represented by the letters “нь“.

While Sakha today is written using the Cyrillic alphabet, with several sounds unique to Sakha and absent in Russian, there are some special letters added to the Sakha version of the Cyrillic alphabet. Some of them are shared with languages like Mongolian. This includes the letters “ү” and “ө“. For the former, take note that this letter is distinct from the Cyrillic letter “у“, which looks more like the Latin alphabet “y”. One of them originates from a ligature called en-ge, “ҥ“, used to represent the “ng” sound in Sakha. Which makes me wonder why the /ɲ/ sound is represented with two individual letters instead of a letter like “њ” found in languages like Serbian. A letter more unique to Turkic languages is the letter “һ” used to represent the /h/ sound, which looks like an inverted “ч“. But perhaps the most unique letter is the letter “ҕ“, which represents the /ʁ/ sound, which sounds like a French “r”.

Among the Turkic languages used in Siberia, Sakha’s grammar has been noted as “unusual”. The first peculiarity I noticed is the distinction made between human and non-human nouns, with different pronouns used for each category in the singular (кини for human, ол for non-human) and plural (кинилэр for human, олор for non-human). To my knowledge, other Turkic languages like Altai and Turkish do not really make such a distinction, with Altai having ол for “he, she, it” and олор for “they”, and Turkish having o for “he, she, it” and onlar for “they”.

Another peculiarity is the way Sakha forms yes-no questions. Instead of using the question suffix -mi found in many other Turkic languages, Sakha chooses to be a little bit different. It uses the question marker дуо, or duo.

But perhaps the strangest of all is the case system of Sakha. Somehow, it lacks the genitive case, the case often used to denote possession-possessor relationships in nouns. Linguists suggest the close linguistic contact with the Evenki language. To express this grammatical function, Sakha uses a possessive suffix on the possessed noun for subject pronouns, and the partitive case -TA for subject nouns.

Sakha retains the comitative case from its ancestral Old Turkic language, which expresses the accompaniment of one noun with another. In other words, it expresses the phrase “together with…”. Linguists suspect that this retention is due to influence from the Mongolian language, as other Turkic languages now use the comitative case as the instrumental case instead. This expresses the phrase “with the…” or “using the…”. In addition to the genitive, the Sakha language has also lost the equative (“like a…”) and the locative (“in the…”, “on the…” etc.).

Despite being quite geographically distant from Mongolian-speaking areas today, the Sakha language has received a significant bunch of loanwords from Mongolian, likely derived from the era of the vast Mongolian Empire, when Classical Mongolian was used. And even weirder, while Sakha is spoken geographically closer to the where the Evenki language is spoken, there are comparatively fewer loanwords entering Sakha from Evenki origin. Furthermore, with the incorporation of Yakutia into the Russian Federation, loanwords of Russian origin have also entered the language, with sounds foreign to Sakha also appearing in the alphabet which it uses. including sounds like /ʃ/, written using the letter “Ш“.

Although the Sakha language today is spoken by a majority of the Sakha people, most Sakha speakers are bilingual in Russian. As such, Sakha is classified as a vulnerable language by the UNESCO Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger, as its use could shift towards Russian in some important circumstances in the future. The main collection of resources covering the Sakha language is in Russian, which I will link here. Perhaps you might also improve your Russian along the way.