How do we define easternmost? Going by longitudes, we might gravitate towards the 180th meridian, or 180°E. After all, this is the easternmost you can go before crossing into the western hemisphere of the world, starting first at 180°W. With this definition, we find the 180th meridian crossing through some bits of land. Barring Antarctica, we have some parts of eastern Siberia in Russia, and some islands in Fiji.

*But there is also another definition we can go by, which gives us a more unanimous answer. That is, how east can you go before you cross the International Date Line? Or better yet, which place celebrates the new year first?

With this definition, our answer would correspond to places so far east they are technically in the western longitudes. But this also corresponds to the most advanced time zone in the world, UTC+14. This is the 8 of the 11 Line Islands that form part of the Republic of Kiribati. The other 3 islands are claimed by the United States, with a designated time zone of UTC-12. This means that visiting the parts of the Line Islands claimed by the United States from its Kiribati counterparts would incur a 26-hour time difference. This time zone is so advanced, it is exactly one day ahead of Hawaii’s time.

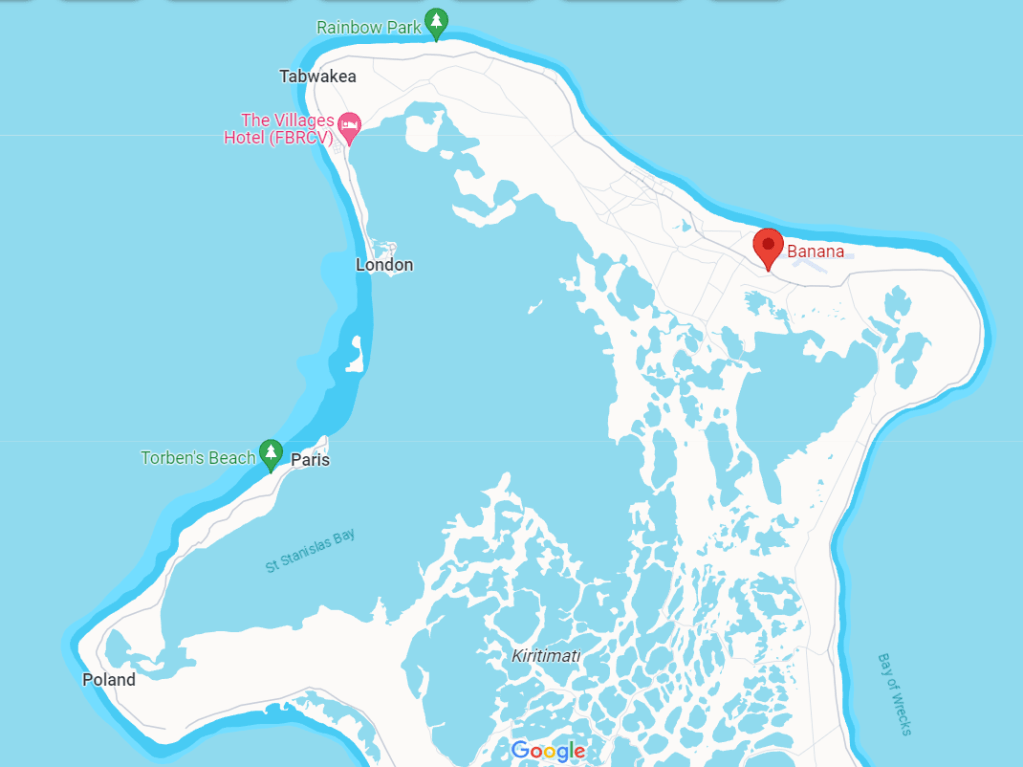

While the easternmost part of Kiribati is Caroline Island, it is uninhabited. The easternmost inhabited island or atoll I can find in Kiribati seems to be Kiritimati, also called Christmas Island. That is also the atoll where you can find places like London, Paris, Poland, and more curiously, Banana. And Banana is perhaps the easternmost settlement in the world by the International Date Line definition.

As with many nations in the Pacific, we would expect some form of an Austronesian language to be spoken in Kiribati. And here, it is called Gilbertese, or Kiribati, or Taetae ni Kiribati. Spoken by more than 100 000 native speakers today, this is the official language of Kiribati, and it is also found spoken in countries like Fiji, the Solomon Islands, and New Zealand.

Kiribati belongs to the Micronesian branch of the Malayo-Polynesian languages, making it more closely related to languages like Nauruan and Marshallese. There are two primary dialect groups of Kiribati, Northern and Southern, but these largely differ in pronunciations of certain words. Perhaps the more deviant ones are the Kiribati used in the islands of Butaritari and Makin, where there are different vocabularies used.

Looking at the Micronesian languages as a whole, there are some notable shared phonological characteristics that we can identify. These languages tend have velarised consonants, distinguished from their plain or palatalised counterparts. There is no sibilant sound, but with one glaring exception.

Kiribati has a considerably smaller phonological inventory than some other Micronesian languages, with 13 consonants, 5 short vowels, and 5 long vowels. This comes in contrast with Marshallese, with a larger consonant inventory, but only 4 phonemic vowels agreed upon by linguists. Interestingly, Kiribati also contrasts consonant length, as long ‘m’, ‘n’, and ‘ng’ sounds exist, although they do not have velarised counterparts. Long consonants are doubled letters when written, just like their long vowel counterparts, while velarisation is denoted with a W after the affected consonant.

In total, the Kiribati alphabet looks something like this:

A AA B BW E EE I II K M MM MW N NN NG NGG O OO R T U UU W

Perhaps the stranger bit is, “t” produces an “s” sound when used before the letter “i”, leading to a somewhat unusual case where there is a sibilant sound in this branch of the Malayo-Polynesian languages. This is also why the word Kiribati is pronounced closer to “Kiribass”, and why Christmas is written as “Kiritimati”.

Another thing that sets Kiribati apart from some other Micronesian languages is its basic word order, or canonical word order. Unlike the subject-verb-object word order we are mostly familiar with in the Austronesian languages, Kiribati takes a little detour, going in the path Malagasy takes. It does verb-object-subject. Take this sentence for example.

E nakonako nakon te titooa teuaarei.

he walk to the store that man.

That man is walking to the store.

Adverbs of time go after the subject, so if you want to say that “that man will walk to the store tomorrow”, it would be “E na nakonako nakon te titooa teuaarei ningaabong“, where “ningaabong” is “tomorrow”.

As you might notice, verbs do not change by person, tense, number, and so on. Instead, these functions are taken up by various particles or suffixes. This is quite common amongst Austronesian languages, so there is no surprise here. Particles of tense precede the verb in most cases, and the suffix -aki denotes the passive voice. The prefix ka-, when used before an adjective, makes it a causative verb.

Verb agreement by person takes place by preceding the verb with a pronoun corresponding to the subject, while the main negation particle, aki, comes after this pronoun, but before the verb. If the context it is used in is something unexpected by the speaker, the particle aikoa is used. So to sum up the basic verb phrase, it is:

pronoun + [tense particle] + [negative particle] + verb

Kiribati also makes use of reduplication, where part of a word, or the entire word, is duplicated to express a certain grammatical or semantic function. Here, partial reduplication of a verb conveys something that is done habitually, while a full reduplication conveys something that is continually done. These two types may be combined to convey something that is done on regular occasions, or something along that line. If partial reduplication is done to form adjectives, it denotes the meaning of “plenty of something”. For example, reduplicating “ka” in “karau” (rain) makes “kakarau“, which means “rainy”.

However, reduplication is not used to form plurals of nouns. That, instead, is done using the plural particle taian, or other means that do not necessitate that particle. Its singular counterpart is te, which also has a nominalisation function, that is, converting adjectives or verbs to nouns. Some words also have a plural form, usually done by lengthening the vowel of the first syllable.

Another interesting pattern I observe is how words for things that the I-Kiribati have never encountered for a long time are translated to Kiribati. Words like ‘ice’ and ‘mountain’ depict things that are never seen in Kiribati, since these are low-lying islands that are situated in the tropics. While Kiribati borrows “ice” directly from English, as “aiti“, and “snow” borrowed as “tinoo“, translating “mountain” takes more of a detour, either borrowing from Samoan myths “maunga“, or just using the word for “hilly” instead, “aobuaka“. This sort of reminds me of Malay, which does not have its own word for ‘snow’, and borrows from Arabic instead, as “salji“.

Other words sound like onomatopoeia, as the word “motorcycle” translates to “rebwerebwe“, which sounds like the noise a motorcycle makes when it is revving up. Some words may also be borrowed from other languages of the Pacific, such as the word for “pearl”, borrowed from Hawaiian as “momi“.

There are some online resources to learning Kiribati. One of those teaches the basics, and I find fairly easy to understand, is this handbook by the Peace Corps. Note that this was originally published in the 1970s, and so the orthography would appear quite different from the one we see today. For example, instead of “bwai“, we see “b’ai “.

This essay would have been slightly different before 1994, as Kiribati pre-1994 used the time zones UTC+12, UTC-10, and UTC-11, which meant that the International Date Line passes through this country. The contenders of the easternmost settlement before this change would have been the country of Tonga, and Chatham Island in New Zealand. Tonga uses the UTC+13 time zone, while Chatham Island uses the UTC+12:45 time zone, but when daylight savings is in place, it uses the UTC+13:45 time zone.

Going by the International Date Line definition of easternmost again, and accounting for longitudes, the town of Pangai or the town of ‘Ohonua in Tonga would have been the easternmost settlements in the world before Kiribati changed its time zones, and we might have covered lea faka-Tonga in this series instead. I hope you have learned a thing or two from today’s introduction, and I will see you all in the next one next week.