What makes a language complex? Is it the grammatical elaborateness of a language, or is it the specific nuances a language can discern through some form of grammatical inflection or otherwise? Investigating this area of linguistics has been mired in controversy and prejudice, as the 19th century view of language complexity hinged on meeting the requirements of ‘an advanced civilisation’. While we have largely moved on from this perspective of language complexity a century later, linguists are still unable to definitely agree upon what a complex language is.

Today, there are several aspects to which complexity can pertain to. An aspect could pertain to a word’s length (or syntagmatic characteristics), as in the number of syllables or constituent parts in a given word. Another aspect would take on a more paradigmatic angle, one that measures how many sounds a language has, or how finely a language’s grammar can distinguish certain nuances. Others would take on a more semantic approach, or how constraints are placed in a language’s grammar when constructing clauses or sentences. Other methods might assess the distribution of information in a language, such as entropy, irreducibility, and connectivity. Yet, measuring how complex a language is is still dauntingly difficult, and there is no agreed upon method of doing so.

This has not stopped some linguists from dubbing this particular language as among the ‘most grammatically complex’ languages in the world, even claiming that this language is the ‘most grammatically complex’ Australian language. These claims are echoed in publications such as a 2011 book by Robert M. W. Dixon titled “Searching for Aboriginal Languages: Memoirs of a Field Worker”, and in the Anindilyakwa Land Council’s website on the language. Linguist James Bednall softened this claim, instead describing this language as “noted for its polysynthetic structure and morphological complexity”. So today, I want to look into the Anindilyakwa language, also known as Amamalya Ayakwa or Enindhilyakwa.

Unlike many of Australia’s indigenous languages, which are either extinct or critically endangered, the Anindilyakwa language seems to be thriving. With around 1500 native speakers, almost all of whom reside in the Groote Eylandt (or Ayangkidarrba) and its surrounding islands in the Northern Territory of Australia, Anindilyakwa is spoken in all, if not, nearly all of the indigenous communities in Groote Eylandt and Bickerton Island nearby. This is further split into 2 moieties containing 7 clan groups each.

Classifying Anindilyakwa has been challenging, as with many indigenous languages spoken around the world. The first linguists studying Anindilyakwa thought of it as a language isolate, and it was classified as such for quite a while. However, the 2010s brought on a proposal for reclassification, that Anindilyakwa was not really a language isolate, but more rather, was related to languages such as Ngandi, and Wubuy or Nunggubuyu. Van Egmond proposed that these languages be grouped together in the Macro-Gunwinyguan language family (or Arnhem, or Gunwinyguan), under the East Arnhem branch, based on an analysis of sound changes, word morphology, verb inflections, and lexicostatistical analyses. This reclassification is further reported in James Bednall’s thesis on the language in 2020.

There is some debate as to how many vowels there are in Anindilyakwa. A 1989 thesis on the language by Velma J. Leeding mentioned a 2-vowel system distinguished by vowel height using the vowels /ɨ/ and /a/, while van Egmond’s 2012 thesis uses a 4-vowel system with the vowels /i/, /ɛ/, /a/, and /ə/. There is more agreement in consonant sounds, with the typical lack of sibilant sounds (and affricates) /s/ and /z/, the inclusion of retroflex consonants, and the lack of voiced consonants like /g/ and /b/. Perhaps the main disagreement I found when comparing the two theses of the Anindilyakwa language was the complex segment consonants identified by van Egmond, which included the consonants [k͡p], [ŋ͡m], and [ŋ͡p], written as ‘kb’, ‘ngm’, and ‘ngb’ respectively.

Anindilyakwa is known for its tendency to form really long words. In fact, most of its words are between 3 and 7 syllables long, with some words getting as long as 14 syllables long. The only 1-syllable words in Anindilyakwa are mostly interjections (think of words like “Ah!”). Some of it could be due to the rather polysynthetic nature of Anindilyakwa grammar, and other features of its word morphology.

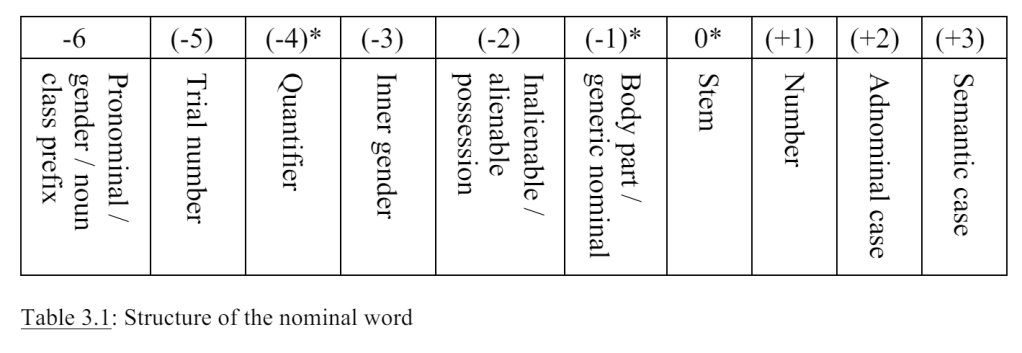

To better illustrate the polysynthetic nature of Anindilyakwa, van Egmond has illustrated the structure of a nominal word. This word class is given to types of words like nouns (dingo, fish, etc.), adjectives (big, small, etc.), pronouns (me, you, etc.), demonstratives (this, that, etc.), kinship terms (mother, father, etc.), and adverbs (quickly, slowly, etc.). Prefixes and suffixes can all be applied to the word stem, to varying extents based on what kind of nominal it is, and what function is necessary. Not all 10 slots are necessarily filled, but this seems to suggest a specific order in which prefixes and suffixes may be attached to the word stem. In fact, only the stem and the pronominal or noun class prefix are necessary in the most basic constructions.

Nouns can be split into five noun classes, with their own corresponding prefixes. Masculine human nouns take n-, masculine non-human nouns take y-, feminine nouns take d- or dh- depending on orthography, neuter inanimate nouns take a-, and vegetables take m-. For some loanwords, these prefixes do not apply, however.

In addition to inclusivity, Anindilyakwa pronouns distinguish between the singular, dual (by male or mixed, and female), trial (that is, three or four of a certain person or object), and plural. This results in pronouns from ngayuwa ‘I’ to nungkwurrubukwurruwa ‘you three or four’.

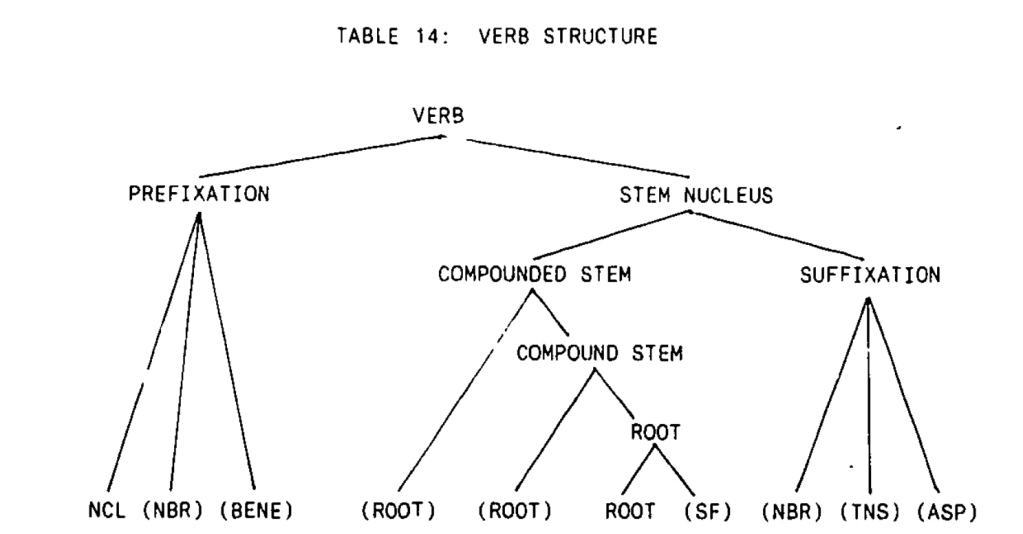

A similar structure of prefixes, suffixes, and root(s) can be seen for verbs as well. This is visualised by Leeding’s thesis, which describes the possible types of prefixes and suffixes allowed in the construction of a verb.

In additional to all of these, verbs can be classified into 6 conjugation classes, determined by the final syllable of the stem or root. For example, verb stems ending in ~bi belong to one conjugation class. Furthermore, there are various kinds of complex verbs which can be fixed, free, or bound, which means more grammatical constraints in their usage, and what could be attached to them to express a certain grammatical function.

Particles such as those denoting causation (-ji-), reciprocity (-jungwV-, V is a vowel), and reflexivity (-yi-) are expressed using suffixes attached to the verb root. The causative particle is mostly applied to intransitive verbs like ‘to fall’ -lharr-, which can convert them to transitive verbs like ‘to drop’ -lharri-ji-. There is much more ongoing research investigating Anindilyakwa verbs, and how the suffixes and prefixes are used, and I recommend checking out the publications listed in Further Reading. Publications by linguists such as Leeding, Bednall, and van Egmond are extremely detailed in dissecting how these particles are used, and how verbs are structured, supporting Anindilyakwa’s status as having a complex grammar and morphology. Take note that as these are linguistics theses and publications, you will encounter a lot of linguistics jargon.

According to van Egmond, Anindilyakwa is the only indigenous language of Australia to have unique number terms beyond 10. Many Australian languages have number systems that only go up to 2, 3, 4, or 5, and often lack number terms to express larger quantities than those numerals. For example, some languages have number terms for ‘one’, ‘two’, ‘three’, and ‘more than three’. But not Anindilyakwa. Anindilyakwa has number terms up to 20, divided in bases of 5. To make numbers like 6 and 14, these would use additions such as “five one” and “ten four”. However, van Egmond’s work revealed that it is unclear if the Anindilyakwa use their number term for 20 today, as English numerals are preferentially used for numbers above 5. Examples of these numerals are shown below:

| 1 | awilyaba | 6 | amangbala awilyaba | 11 | ememberrkwa awilyaba |

| 2 | ambiyuma | 7 | amangbala ambiyuma | 15 | ememberrkwa amangbala / amaburrkwakbala |

| 3 | abiyakarbiya | 8 | amangbala abiyakarbiya | 16 | ememberrkwa amangbala awilyaba / amaburrkwakbala awilyaba |

| 4 | abiyarbuwa | 9 | amangbala abiyarbuwa | 20 | wurrakiriyabulangwa |

| 5 | amangbala | 10 | ememberrkwa | 21 | wurrakiriyabulangwa awilyaba |

There are also a bunch of loanwords in Anindilyakwa, stemming from interactions the Anindilyakwa people have had in their history. Among these loanwords, the most significant language of origin is Makassarese, an Austronesian language spoken in the Sulawesi region in Indonesia. The Makasserese visited the coastal and insular areas of northern Australia to establish trading relationships, bringing foreign goods such as tobacco and tamarinds to trade. With these goods, also came foreign words that entered the Anindilyakwa language. Words like jamba (from jampa, tamarind) entered the language, along with, interestingly, Makassarese words for maritime navigation such as wind directions. Makassarese words for some tools like axes, knives and machetes also entered Anindilyakwa use. Nowadays, words of English or western origin may have entered Anindilyakwa, through the form of other introduced technologies or animals. Among these, interestingly, is the now Anindilyakwa word for ‘deer’, called bambi.

Despite the thriving speaking community today, the language is still classified as vulnerable by the UNESCO Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger, with more pessimistic opinions classifying it as definitely endangered. While the more pessimistic classification is most likely derived from the small speaking population, the ‘vulnerable’ classification could be attributed to threats facing the language. Many speakers of Anindilyakwa also speak English, the most predominant language in Australia. It is perhaps the risk of language shift in Anindilyakwa communities towards English which could threaten to endanger their language.

Nevertheless, Anindilyakwa is reported to have seen an increase in the number of native speakers over the period of 2006 to 2021. According to Australian census data, the number of Anindilyakwa native speakers grew from 1283 individuals in 2006 to 1516 in 2021. There is active transmission and education of Anindilyakwa to younger generations, and there is also active maintenance, lead by the Groote Eylandt Language Centre through efforts such as the Ajamurnda project and dictionary projects. With additional representation in popular culture, these efforts ensure the survival of the Anindilyakwa language in the years to come.

Further Reading

Introduction to the Groote Eylandt Language Centre and its projects:

https://anindilyakwa.com.au/preserving-culture/language-centre/

https://www.anindilyakwa.org.au/our-language/

https://www.dnathan.com/eprints/cfletcher_etal_2017_ajamurnda.pdf

Ayakwa – Anindilyakwa dictionary online:

PhD theses and publications covering Anindilyakwa grammar:

https://jamesbednall.com/anindilyakwa.html

Bednall J. (2021) Identifying Salient Aktionsart Properties in Anindilyakwa. Languages, 6(4), 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6040164.

Bednall, J. (2020) ‘Temporal, aspectual and modal expression in Anindilyakwa, the language of the Groote Eylandt archipelago, Australia’, Doctor of Philosophy, Australian National University. https://doi.org/10.25911/5e3a935248011.

Leeding, V. J. (1989) ‘Anindilyakwa phonology and morphology’. Doctor of Philosophy, University of Sydney. https://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/handle/2123/1558.

van Egmond, M. (2012) ‘Enindhilyakwa phonology, morphosyntax and genetic position’. Doctor of Philosophy, University of Sydney. https://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/handle/2123/8747.