Recently, I have found myself back in the mood of learning te reo Māori more seriously, as I take larger strides in learning and familiarising myself with the words of the language. While some words sound like loanwords that have entered Māori, some others remind me of languages like Malay or Indonesian.

But there is this class of words that has intrigued me for some time, and I thought I would share what I have learned about these words. Gaining a deeper insight into these words has also taken me on an astronomical ride, so there is quite a bit to unpack here.

These words pertain to the names given to the months in Māori. Learning from Drops, the language application I have covered several years ago, the Māori words for the names of the months are:

| January | Kohitātea |

| February | Huitanguru |

| March | Poutū-te-rangi |

| April | Paenga-whawha |

| May | Haratua |

| June | Pipiri |

| July | Hōngongoi |

| August | Here-turi-kōkā |

| September | Mahuru |

| October | Whiringa-a-nuku |

| November | Whiringa-a-rangi |

| December | Hakihea |

Curious, I began to read on about the etymologies of these names of the months. But this was when I realised I uncovered a strange rabbit hole. That te reo Māori traditionally did not have a standard system of naming months. To refer to July, for example, one might encounter several different words, depending on the iwi (or tribe). This perhaps raises a question about which convention the Māori language proficiency tests in New Zealand use, would it most likely be the transliterations from English, or would they lean more traditional? More confusingly, some sources, especially obtained from South Island of New Zealand, mentioned 13 month names instead of 12. So what is going on here?

Pouring through sources like The Maori Division of Time by R. E. Owen, and the Museum of New Zealand (or Te papa tongarewa) websites, I learned that these Māori months pertained to the lunar calendar, which at 29 or 30 days long, do not nicely fit into the 365.25 days that constitute a year. While most iwi use a 12-month-long system, there are about 11 days left over to account for to make up the full year. Some iwi might opt to make a 13th month every few years, while others would use a different system of accounting for those 11 days. So that forms the sort-of basis of the differing number of month names between Māori communities.

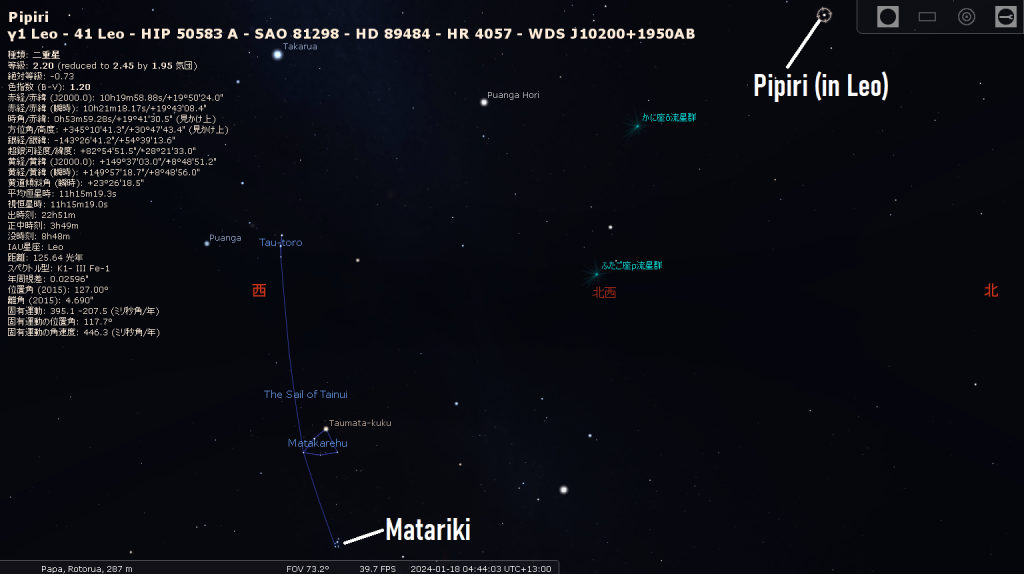

Interestingly, the Māori new year starts in June or July, with the first rising of Matariki, or the brightest star in the Te Kāhui o Matariki or Pleiades star cluster, Alcyone. Some iwi might celebrate with the first rising of Puanga, or Rigel, in the Orion constellation. But the month it corresponds to is generally called Pipiri. Consulting Te Aka Māori for its meaning, it turns out that this also refers to certain stars in Aries that rise before Matariki. And looking these stars up on Stellarium, there is also a star called Pipiri in the constellation of Leo, which rises earlier than Matariki.

Now, we can get into how the months are named. The simplest month names primarily use numbers in Māori, something along the lines of Te Tahi (The First, or June), Te Rua (The Second, or July), Te Toru (The Third, or August), and so on. Ignoring the differences in the lunar calendar systems, it reminds me of the names of the modern months in Chinese and Japanese, such as 一月 (January), 二月 (February), 三月 (March), and so on.

This is where things take a more complicated turn, especially varying from community to community. Remember the month names on Drops? The main resource I could find covering them point towards Tūtakangahau’s, a Ngāi Tūhoe chief’s, descriptions of the Māori months, which he provided to an ethnographer named Elsdon Best. These descriptions mostly tell us of natural processes and man’s actions during the months, but does not really point us towards an etymological root for the names of the months, nor what they really refer to.

In the month of Pipiri, New Zealand enters the winter months. This is when things become cold, and hence the word pipiri in this context, which sort of translates to “frozen” or “freeze”.

The second month in the Māori calendar, Hōngongoi or Hōngonui, generally corresponds to the coldest month in the southern hemisphere, July. The description provided by Tūtakangahau, quote “Kua tino mātao te tangata, me te tahutahu ahi, ka pāinaina“, translates to “Man is now extremely cold, and so kindles fires before which he basks”. It talks about man’s actions in reaction to the cold of July.

This is followed by Here-turi-kōkā. This is not listed on Te Aka Māori, though alternatives like Te Toru Here Pipiri and Here o Pipiri are provided. The Tūtakangahau description generally illustrates the direct consequences of Man’s actions in Hōngongoi, which heats his knees.

Mahuru is the month which when the earth is described to have “received warmth”, and vegetation has come to life. This month corresponds to September, where spring in the southern hemisphere is just starting.

Turning up the heat, we arrive in Whiringa-a-nuku, when the earth has become “quite warm”. This leads into the sixth month of the Māori calendar called Whiringa-a-rangi, when summer has started in the southern hemisphere. The next month, Hakihea, is when birds are observed to rest in their nests. This alludes to several things. It could be hot to the point where birds have to rest in their nests, or for New Zealand’s native birds, it would be their mating seasons, and these bird species would be preparing to raise a new brood of chicks.

The eighth month is called Kohitātea, but also goes by other names like Rehua, Maramatahi (Month one, January). and Kai-tātea (used by the tribe called Ngāti Awa). It describes the start of the harvest season, when fruits and crops ripen, ready to be picked and harvested by man.

The ninth month, Huitanguru, takes a bit of an unusual turn. Tūtakangahau describes it as “Kua tau te waewae o Ruhi kai te whenua“, translating as “The foot of Ruhi now rests upon the Earth”. I had to explore further to figure out what or who Ruhi is, and the closest I have found is the name Rūhī, which is a name given to a star in the Māori constellation Ta Waka o Mairerangi, or The Great Boat of Mairerangi. This corresponds to some stars in Scorpius. In Māori folklore, Rūhī and Pekehāwini, another star in the constellation, were the wives of Rehua, the brightest star in Scorpius, and Pekehāwini‘s appearance marks the month of Kohitātea, or Rehua (basically the preceding month). My Stellarium did not quite show these stars, nor the constellation in mention, though it shows where Rehua and Pekehāwini are in the night sky.

Returning from this constellation trip, the tenth month of the Māori calendar describes the end of the harvest season, called Poutū-te-rangi. Interestingly, there is a star called Poutū-te-rangi, corresponding to the brightest star in Aquila, Altair. It should appear with the star Whānui, the brightest star in the constellation Lyra, corresponding to Vega.

The second last month of the calendar is Paenga-whawha or Paenga-whāwhā, which describes the storage of straw in preparation for winter. And in the last month of the Māori lunar calendar (if a 12-month system is used), Haratua, it describes the conclusion of Man’s preparation for the winter, when all crops are stored.

This is just one variant of names of the months, though. Te Aka Māori lists the names of the months in two other particular tribes, namely the Ngāti Awa and the Ngāti Kahungunu, while providing other variants, and the corresponding name of the star to the respective month. However, etymologies are not quite known. And so, these names of the months could be organised into a table, although there are other tribes who use other variants for certain names.

| Month (in Māori lunar calendar) | Numerals | Ngāi Tūhoe, some other tribes etc. | Ngāi Awa | Ngāi Kahungunu | Other variants | Associated star[s], planet |

| 1 | Te Tahi | Pipiri | Te Tahi o Pipiri | Aonui | Maramaono, Mātahi [o te tau] | Matariki (Alcyone), Puanga (Rigel) |

| 2 | Te Rua | Hōngongoi, Hongonui | Te Rua o Takurua | Te Aho-turuturu | Maramawhitu, Maruaroa, Takurua | Takurua (Sirius) |

| 3 | Te Toru | Here-turi-kōkā | Te Toru o Hereturikōkā | Te Iho-matua | Maramawaru, Here o Pipiri, Aroaro-māhanahana, Māngere[mumu] | Te Toru Here Pipiri (Perseus constellation) |

| 4 | Te Whā | Mahuru | Te Whā o Mahuru | Tapere-wai | Maramaiwa | Mahuru (Alphard) |

| 5 | Te Rima | Whiringa-a-nuku | Te Rima o Kōpū | Uru-Tahi | Maramatekau, Kōpū, [Rima o] Hiringa-a-nuku | Kōpū (Venus), Whetūkaupō (Deneb) |

| 6 | Te Ono | Whiringa-a-rangi | Whitiānaunau | Uru-Tautahi | Maramamātahi | Whetūkaupō (Deneb) |

| 7 | Te Whitu | Hakihea | Hakihea | Akaaka-nui | Maramamārua, Te Whitu o Hakihea | Hakihea (Alpha Centauri) |

| 8 | Te Waru | Kohitātea | Kai-tātea | Ahuahu-mataora | Maramatahi, Te Waru-o-Kaitātea | Rehua (Antares), Pekehāwini (in Scorpius) |

| 9 | Te Iwa | Huitanguru | Rūhī-te-rangi | Iho-mutu | Maramarua | Rūhī (in Scorpius) |

| 10 | Te Ngahuru | Poutū-te-rangi | Poutū-te-rangi | Putoki-o-tau | Maramatoru | Ō-tama-rākau (Formalhaut), Poutū-te-rangi (Altair) |

| 11 | Te Ngahuru mā Tahi | Paenga-whawha, Paenga-whāwhā | Paenga-whāwhā | Tīkākā-muturangi | Maramawhā, Mātahi o te tau | Paengawhāwhā (Pegasus constellation) |

| 12 | Te Ngahuru mā Rua | Haratua | Hakiharatua | Uruwhenua | Maramarima, Kāhuiruamahu | — |

But hold on, earlier, I mentioned that some sources claimed that there might be 13 months in the Māori lunar calendar. What is the 13th month called then?

The short answer is, it is not very clear to me. Once again, the traditional name differs from iwi to iwi, and most tribes use the 12-month convention anyway. Some sources say that this 13th month has to do with the star Puanga, which is sometimes referred to as the “harbinger of the new year”. Others suggest “Te Tahi o Pipiri“, or “The First of Pipiri”, which coincides with the name for the first month of the year as used by Ngāi Awa speakers. A South Island variant might suggest something along the lines of “Matahi o Mahurihuri“, but this is sourced from ethnographer John White in the 19th century, and it does not seem that I could find a more recent source. The Maori Division of Time is a source from the 1950s. but has information that is consistent with Te Aka Māori. In any case, it seems that this 13th month system might not be commonly used in Māori speakers today.

The Maori Division of Time goes on further, exploring the month names given in other languages like Moriori, Cook Islands Maori, and Hawaiian, and I recommend further reading in those parts if you are interested in comparing the names of the months across the Polynesian languages. There could be some similarities shared in folklore, particularly pertaining to constellations and star names, and are worth exploring deeper into. With Polynesian cultures known for maritime navigation, it is interesting to explore how such navigation techniques are developed, which may be woven into folklore and tradition.

Lastly, there are Māori month names that derive directly from the English counterparts. These month names are generally more intuitive to figure out, as they are English month names that are modified to fit Māori phonological rules. These are, from January to December, Hānuere, Pēpuere, Māehe, Āperira, Mei, Hune, Hūrae, Ākuhata, Hepetema, Oketopa, Noema, Tīhema. Take note, however, that these transliterated months do not quite correspond precisely with the traditional Māori names for the respective lunar months.

So this has been an interesting but also rewarding dive into a certain category of words in te reo Māori. Reading deeper into this topic exposed me to some cultural roots of the names of the months, as well as a small taster in Māori folklore. What I learned is, traditionally, there is no standardisation for the names given to the lunar months. Some of these months correspond to appearances of certain stars in the night sky, which are pretty often among the brightest stars. If you are a stargazer who chances upon this essay, perhaps you might switch your Stellarium to show Māori constellations, and explore the corresponding names of familiar stars in the Māori language.