If you have visited Maya ruins across Mexico, Guatemala, and Belize, particularly in the Yucatan Peninsula, such as Tikal, you might have encountered some stone walls or bricks with some graphic inscriptions on them. They may seem to blend in, or resemble the graphic carvings of figures, deities, or the like they are found with, but little would you know, these block-like characters are actually part of a writing system. This is perhaps one of the most well-known writing systems of Pre-Columbian Central America, which still garners intrigue and interest to this very day.

Each character block looks really intricately carved, making this writing system one of the most graphically elaborate ones to have ever existed. This became one of the most definitive characteristics of the Maya Civilisation, which arose perhaps as far as the 3rd millennium BCE, and declined by the turn of the 10th century, fading into relative obscurity in the 13th century. Mayan languages continue to be spoken to this day, but how these glyphs were written and read had been long lost. For centuries, many believed that these stone inscriptions did not constitute a writing system, or a functional one at that. Early decipherment mistook this for an alphabet too.

But what was the Maya script actually? In the 1950s, the ethnologist Yuri Valentinovich Knorosov postulated that the Maya script, as pictographic as it looked, was at least partly phonetic, and that represented the Yucatec Maya language. While initially met with disagreement by many academics of that time, this postulation would eventually lead to a breakthrough in modern deciphering efforts.

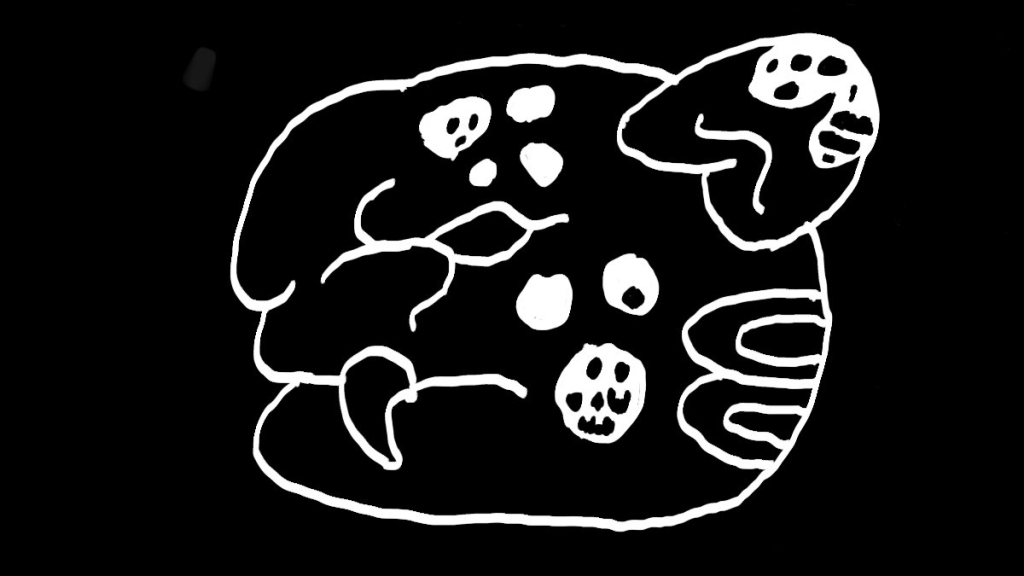

The Maya script is a logosyllabic script consisting of hundreds of logograms, syllabograms, and glyphs representing place names, gods, and other words. In a way, you might draw some similarities between the Maya script and Japanese writing, as logograms could be compared with Japanese kanji, while the syllabograms could be compared with hiragana and katakana.

Thus far, there are glyphs for almost every syllable in the Mayan languages, at least when it was spoken way back in the day. While there is not really a many-to-one relationship between syllable and glyph, there is a one-to-many relationship between them. One syllable may be transcribed by multiple possible glyphs. This makes up a total of around 550 logograms, and 150 syllabograms currently identified. More glyphs could theoretically exist, although the steles and manuscripts potentially containing them remain to be found. These glyphs are read in columns of two, from left to right, and then top to bottom.

Maya numerals use a base-20 system, with three possible glyphs representing them. Zero is represented by a shell, a dot represents one, and a bold line represents five. The numbers 6-19 could be written horizontally or vertically, but every number above that is written vertically, read from top to bottom in powers of 20. That is, the second-lowest number represents the number of 20s, the third-lowest number represents the 400s, and so on.

Now, we get to the actual reading of Maya glyphs. Many sources like to use the example of the glyph and Maya word for the animal ‘jaguar’, b’alam. This could be entirely represented by the jaguar glyph, but you could also write it entirely with the syllabograms corresponding to b’a, la, and ma. Alternatively, you could use both systems, writing it as the syllabogram for b’a combined with the jaguar glyph, the jaguar glyph combined with the syllabogram for ma, or even more convolutedly, b’a + jaguar + ma.

But these syllabograms serve additional purposes. They could help distinguish logograms that have more than one reading, or assist in writing grammatical bits that cannot be represented by a logogram.

While the structure of a syllabogram is typically (C)V, Mayan syllables can take the form CVC, where C is a consonant, and V is a vowel. Mayan syllables may also contain long vowels, represented as CVVC, and glottalised vowels, represented as CV’C or CV’VC. As these are not really represented by the syllabograms identified in the Maya script, here are just some of the orthographical rules linguists have managed to identify.

Do you want to write a CVC syllable but the syllable ends in a /l/, /m/, /n/, /’/, /h/, or /x/? Then in some cases, you do not need to write that consonant’s corresponding syllable at all. This is called ‘underspelling’. But in cases where you have to write that syllable, this is usually followed with an extra vowel, usually matching the core vowel. So if you have to write kah (fish fin) in syllabograms, you would use the syllabograms for ka and ha.

What if you need to write a syllable containing a long vowel? In this case, the syllabograms for CV-Ci would be used. If you needed to write the syllable baak, you would use the syllabograms for ba and ki.

But what happens if the long vowel is /i:/? That would clash with the orthographical rule for CVC syllables. In this case, the Ca glyph is used in place of that Ci. Thus, if you want to write yihtziin (younger brother), you would use the glyphs yi, tzi, and na.

Lastly, what happens if you want to write glottalised vowels? There are two patterns that correspond to this type of vowel, depending on the quality of the vowel in the syllable. If the core vowel is /e/, /o/, or /u/, you would use the Ca glyph in the final. But if the core vowel is /a/ or /i/, you would use the Cu glyph instead for the final. Therefore, if you want to write hu’n (paper), you would use the syllabograms for hu and na. Similarly, if you want to write ba’ts’ (howler monkey), you would use the syllabograms for ba and ts’u.

Although it has been centuries since the Maya civilisation faded into obscurity, certain Maya-speaking populations continued using it up until the 16th century, particularly by the speakers of Yucatec Maya. Today, while many examples of the Maya script exist in steles, codices, and various stone pyramids or temples, there are ongoing efforts to revive the writing system, garnering more interest in what is already a fascinating script.

This would present several challenges down the road, as the various Mayan languages have since undergone changes in sounds, such as the rise of the /p’/ sound in the Yucatecan and Ch’olan branches. These new sounds may not be adequately captured by the Maya script, perhaps necessitating further changes to properly adapt the Maya script for modern use.

Another problem is digitisation of Maya. Today, there is no character encoding method that properly accommodates the Maya script, but there are ongoing projects dedicated to develop mechanisms in which Maya could be digitised. And this is just to adapt the Maya script for modern use. To transcribe Classical Maya, however, the orthographic features of Maya, particularly the flexibility, variation, and the insertion of certain signs into other components, pose as daunting challenges to the digitisation of Classical Maya.

Nevertheless, there are modern Maya poetry written today, entirely in the Maya script. One of the most prominent examples is the Tzeltal language poem called Cigarra, or Xiktiin. Alongside the Maya script, its transcription, the Latin alphabet version, and Spanish translation of the poem is also given for any reader to admire. Perhaps with continued modern interest in the Maya script, this writing system could see its own rebirth, much like the revival of the Meitei script, which had been replaced with the Bengali script from the 18th to 20th centuries. Despite the challenges in digitisation, we could hold some optimism in the renaissance of the Maya script.