This is a subject that may seem out of the blue here on The Language Closet, but it is something I want to get off my chest. After all, having a background in science, and a particular enjoyment in reading up on topics in linguistics, it is inevitable for me to at the very least, look up Google Scholar for articles and publications covering these various topics. But 2024 has brought to light a rather concerning phenomenon happening in the world of academia. That of possible academic dishonesty.

I am sure that we are not new to the phenomenon of academic dishonesty as a whole. Improper reporting, fabrication of data, and other kinds of unethical acts have occurred time and again in academia, which leads to publications that seem too unintuitive to be true. After all, who would not want to make breakthroughs in their field? Who would not want to gain some sweet juicy citations and more lines in the publications section in their curriculum vitae? Who would not want to make money as a publisher? To some, the allure of these accolades and advancements would compel some to use underhanded tactics to get their way.

Examples have been seen in the race to discover new elements, the alleged fabrication of laboratory data to support the discovery of elements 116 and 118 in the late 1990s, the first of their kinds back then. Another potential example is the ongoing scepticism surrounding LK-99, a purported scientific breakthrough in the field of superconductors in 2023. And on a medical side, there is the scrutiny placed on the amyloid hypothesis for Alzheimer’s disease, where some high-profile cases of alleged academic fraud have been brought up in 2022.

But today, there is also a new trend arising in academia. I am sure you have heard of artificial intelligence (AI), especially those of the generative kind. You know, the sort of technology that has threatened to take over the livelihoods of creatives. Apart from various controversies from how data is gathered to train models, bias in models, and how generative AI has already been used to promote fraudulent material, we have to talk about its encroachment in academia as well.

The main study that was brought to light was the paper that was published (and later retracted) in Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology in February 2024. Readers pointed out the blatant use of generated images as figures in the paper, including one with a rat with comically enlarged genitalia. This very image has gained widespread online mockery, and has placed many eyes on the issue of the use of generative AI in scientific journals. Fortunately, the paper was retracted having lasted a mere 3 days in publication.

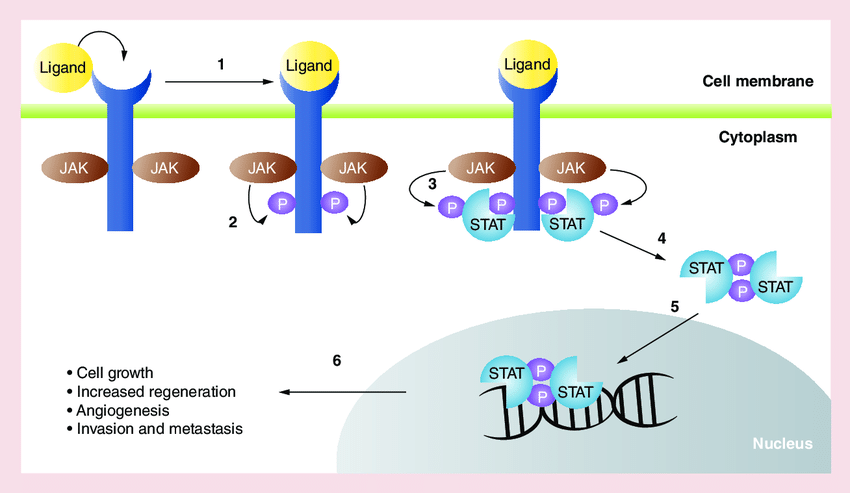

The figure in the retracted article has a completely inaccurate depiction of the JAK/STAT signaling pathway. Compare this with the image on the right depicting the same pathway, drawn up without generative AI (Tang et al., 2020).

Peering through the mockery of the rat image, there are still some glaring questions to be addressed. For one, how did this pass peer review? Why did these images fall under the radar, only to be openly mocked once the article is published? Are there other parts of the manuscript that have been generated by AI, but were not reported by the authors?

We sort of have an answer from one of the peer reviewers in charge of this paper. According to this VICE article, they responded, “As a biomedical researcher, I only review the paper based on its scientific aspects. For the AI-generated figures, since the author cited Midjourney, it’s the publisher’s responsibility to make the decision.” From this comment, it appeared that the peer reviewer shirked off their own responsibilities to ensure that the figures are representative of the present scientific literature present, you know, accuracy. Figures are meant to be informative visualisations of processes or data to communicate information and findings to the reader. These images should be representative of the textual paragraphs that describe them, providing a key visual aid in the paper. Even if the authors submit such images due to lazy research or some negligent circumstance, these should have been picked up by reviewers who get a hold on it, and worked upon when pointed out.

As these images have very obviously failed to represent factual accuracy, there are some questions surrounding the extent to which the manuscript has been generated by some form of AI. I have taken a look at the textual contents of the paper, and there were some glaring thematic inconsistencies. For one, the abstract of the paper alluded to mammalian spermatogonial stem cells or SSCs, as illustrated by that infamous image. However, most of the studies cited in the article mentioned an organism called Drosophila. That is a fruit fly. Furthermore, in the sections where they did use studies on rat or mouse SSCs, there was no actual link to the titular pathway. These issues were also noticed by other readers who are much more informed in this field of biology than I am, and they also pointed out more issues in the paper.

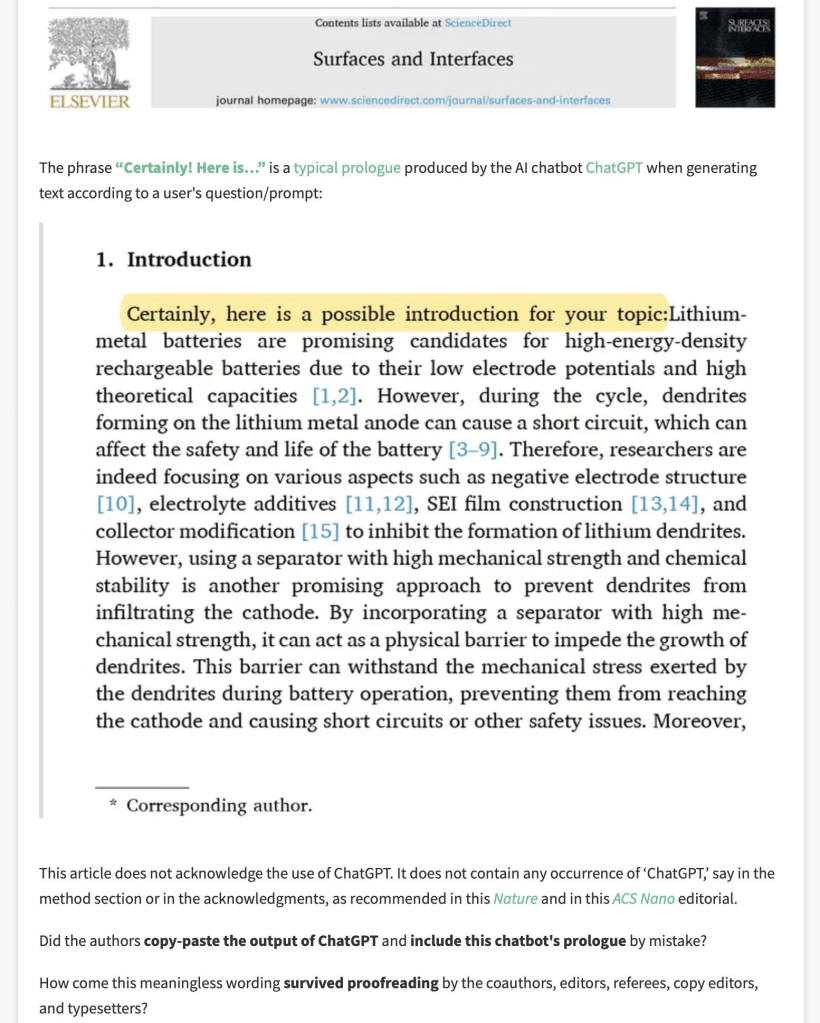

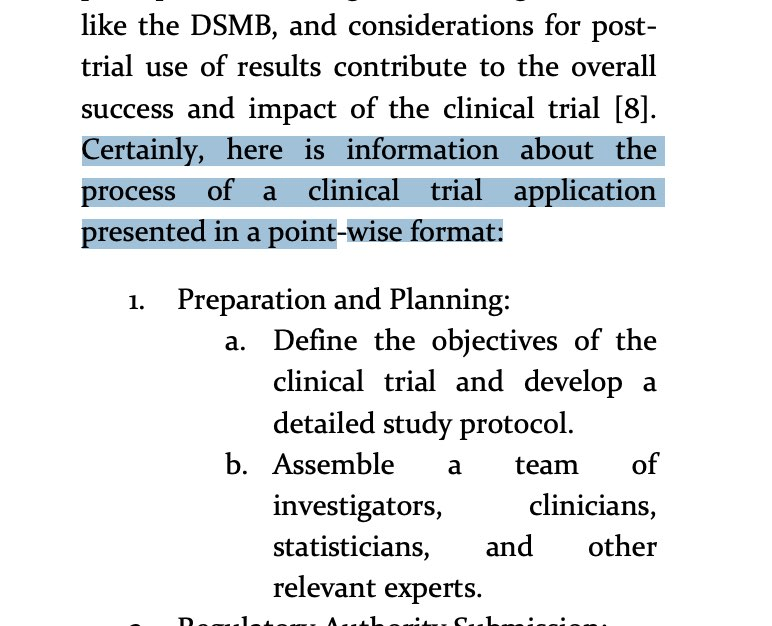

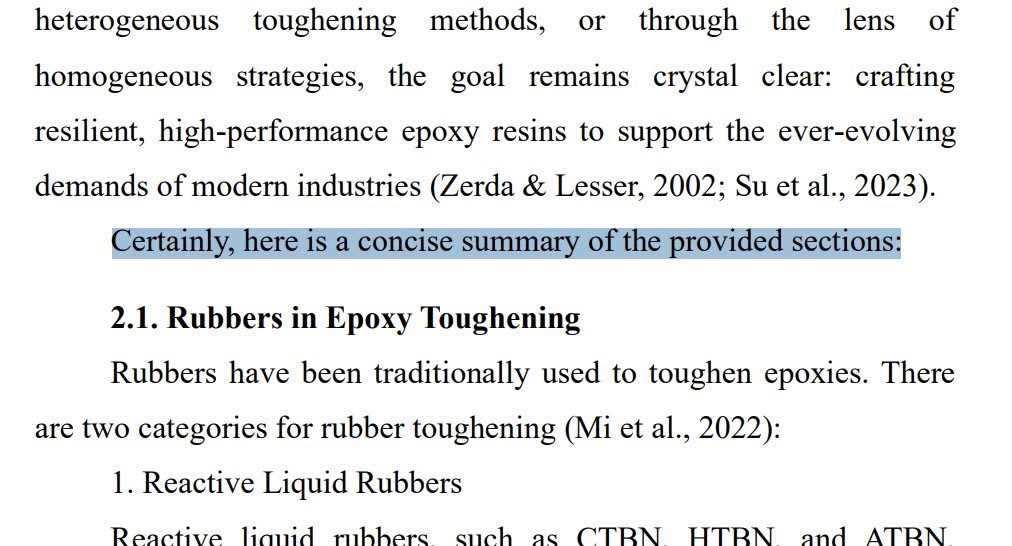

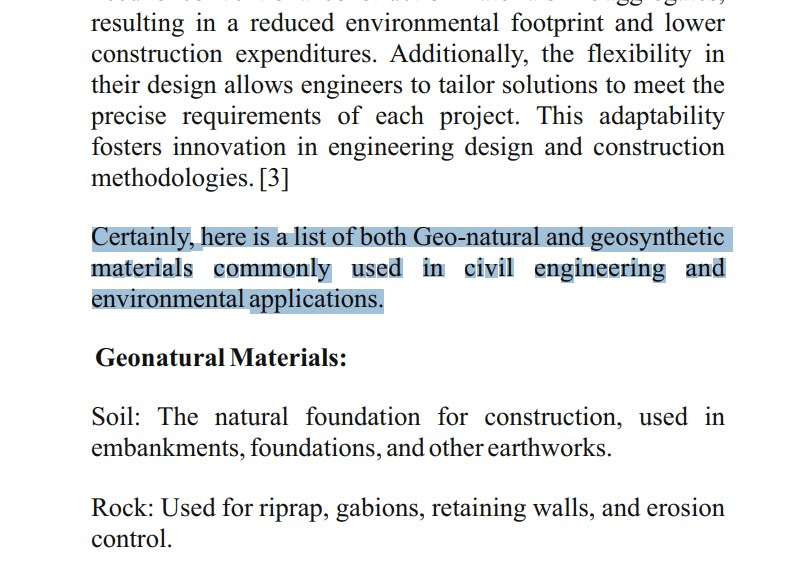

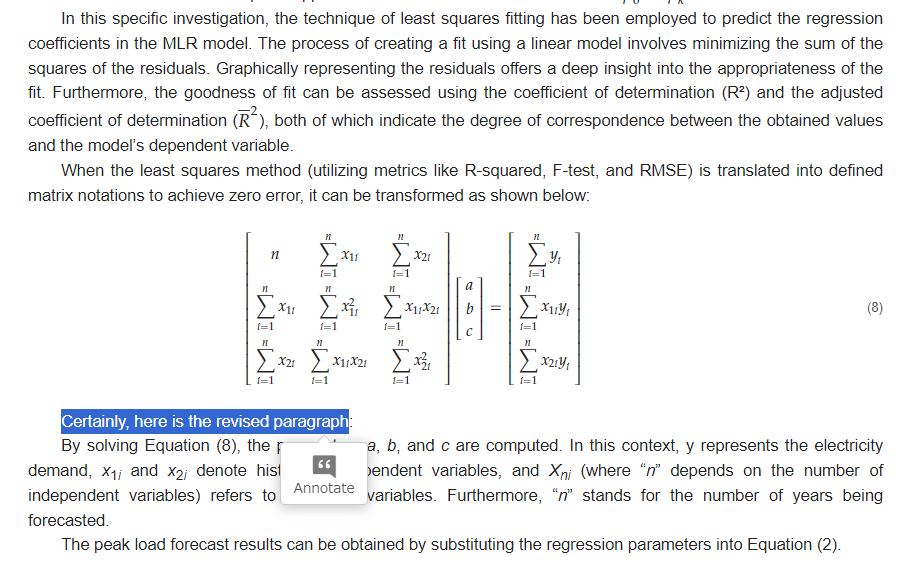

This brings us to the other methods in which generative AI has invaded academia. These could be more prominent, while many others could be more clandestine. In March 2024, I was alerted to some publications where generative AI has been used to “write” the manuscript, leaving obvious hallmarks of it being generated. The main phrase I have come across is “Certainly, here is”, a signature that that particular text is generated using ChatGPT. You could look it up on Google Scholar, using the signatures as search terms in quotation marks, and perhaps a few more limiters such as -chatgpt and -llm. All of the following articles were searched using this search format, except the first one below that introduced me to this phenomenon.

This phrase has also been seen when generating references, as shown here:

There are also more hilarious examples of this, such as this one, with an exclamation mark, a punctuation mark almost never heard of when it comes to academic writing.

More hilarious hallmarks of the use of generative AI in “writing” manuscripts can also be seen when the authors somehow forgot to crop out the ending of a response, that prompts the user to regenerate the response given by whichever large language model they are using.

The last pattern of obvious tells is when ChatGPT tells the user that it is a “large language model” or something along those lines. This has been pointed out by this X / Twitter user using this article as an example:

This prompted me to look up on more examples of this, and they did not disappoint in terms of the examples I found. They did disappoint me by the fact that these got the green light from the reviewers, got published, and are still up to this day.

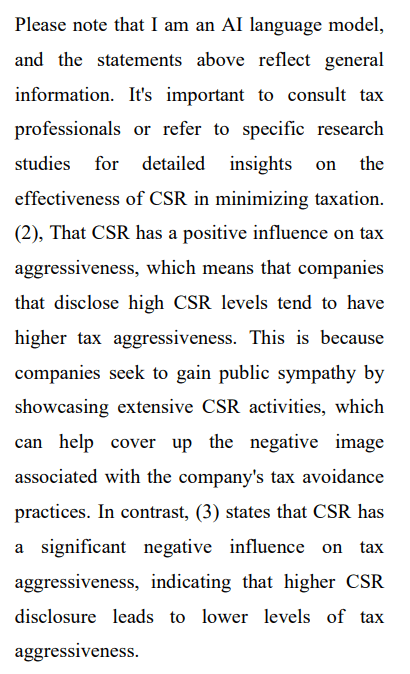

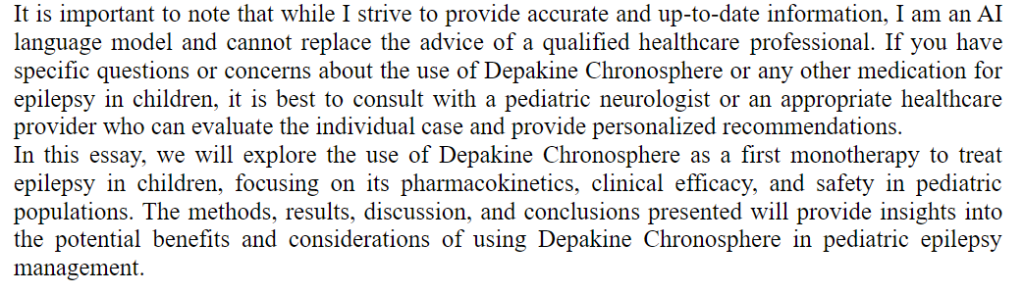

The image on the left is from this paper, while the image on the right comes from this paper, and it is perhaps the worst offender when it comes to lazy research. If you read this AI-generated manuscript, you would find that that publication is entirely uncited, with some references thrown in at the end for some sort of attempted legitimacy. It seemed that references were just an afterthought, or possibly even AI-generated, demonstrating how lazy the “authors”, if you could call them that, were when it comes to generating this article. This article should never have made it past submission, but alas, it was published.

We may laugh and gawk at such examples of generative AI showing itself out in the open, but this underscores a more concerning trend that is just only being exposed. The main question I had was, how did all of this pass peer review? Isn’t the point of peer review to function as a sort of quality control to ensure the manuscript meets the reporting and quality standards set out by the journal or publisher? With such obvious signatures of the use of generative AI in the manuscripts, published manuscripts no less, these articles would and should never have been published as they are if peer review actually happened.

While we may criticise the lack of quality control or enforcement of standards when it comes to manuscripts of this quality, I also wonder about the magnitude of this problem; how many more AI-generated manuscripts have been published under our very noses? Authors could have cropped out the obvious signatures left in the text by large language models, or intercalating these responses with the authors’ own input, but never quite reporting the use of generative AI in writing the manuscript or part thereof. It underscores a concerning phenomenon happening in the world of academia and academic dishonesty, and one that could potentially undermine the credibility of the academic body.

The implications of this trend, in my opinion, are quite telling. With the potential of large language models to hallucinate, it could open up more cases of fraudulent reporting, and undermining the credibility of certain literature as a whole. If a large language model was prompted to write something about a scientific breakthrough, it very well could, even when no such thing exists. Researchers, anyone in academia, and the general public should not be defrauded by AI hallucinations. Perhaps this is why journals have enacted their own policies on AI-generated content, which, as we have seen in the examples shown above, still have loose ends that urgently need to be tied up.

The requirement for AI-generated content to be labelled as generated by whichever model used in journals is extremely lax, like a plaster on an amputated appendage. This is even when there is a requirement to ensure these generated images or content meet the reporting guidelines of the scientific journal. For instance, Frontier’s policy on AI generated figures is, the author is responsible for checking the factual accuracy of any content created by the generative AI technology. This includes, but is not limited to, any quotes, citations or references. Figures produced by or edited using a generative AI technology must be checked to ensure they accurately reflect the data presented in the manuscript. And when it comes to the publisher Elsevier, this is what they have to say in response to the publications with signatures of the involvement of ChatGPT:

I think that the use of AI-generated images and text in manuscripts should be prohibited with almost no exceptions, as seen by the authors failing to do their due diligence in truthful reporting of AI-generated manuscripts, or their failure in ensuring figures meet factual accuracy, and the peer reviewers, who have obviously let this slide, negligently or deliberately. However, it is also an arms race to detect and filter out generated content, as AI just learns to be more discrete in leaving its own signatures here and there in the manuscript. At the very least however, the AI-generated papers that have been published in journals and still are should be retracted. Perhaps we should make the editors and reviewers of those respective journals and publishers aware of our concerns, to advocate for a more enforced stance on the use of AI in generating texts or images in manuscripts.

It must be made clear that AI is inherently naïve. They have to rely on large amounts of data to identify patterns in language, such that they could generate textual responses in the possibility that those are what the user wants. They might not know what a certain stem cell is, but have been trained to associate certain words with what stem cells are. Generative AI is extremely vulnerable to inaccuracies, as the given data they are trained on it its many iterations may not reflect factual accuracies at times. By taking their responses as gospel, the user would be at a certain risk of being misinformed. In a field where communication of scientific findings is crucial, generative AI should never have been allowed in the first place.

The general pattern of articles showing clear signs of AI-generated input seems to lie predominantly in review articles. These are articles that summarise the current literature pertaining to a certain scientific topic, which do not necessarily entail the reporting of methods used in conducting the review. However, one must ask, how long would it be before these inputs start to creep into experiments or primary research? Would anyone trust the credibility of an AI-generated protocol or an AI-generated methodology of a clinical trial? While it sounds like I might be making a slippery slope fallacy, given the recent advancements in generative AI, and the possibility of more AI-generated articles flying under the radar in academia, these questions do not seem that strange.

Despite the presence of AI-generated articles in journals, we should not discount ongoing efforts to identify and retract dishonest or potentially fraudulent research. In fact, according to Nature, a record high of over 10 000 research papers have been retracted in 2023 alone. It was a major uptick compared to 2022, in which around 5000 papers were retracted, according to Retraction Watch. While many of these retractions were attributed to dishonest contributions and paper mills, we might potentially start to see a growing proportion of retractions due to AI-generated manuscripts and images. This trend in paper retractions underscores the growing threat of academic dishonesty and demonstrates the escalating fight to combat such unsavoury practises.

Going into 2024, the retraction of the paper with the comically-enlarged rat genitalia is just the tip of the academic iceberg when it comes to identification and retraction of papers that do not meet reporting standards of the respective journals or publishers. But this could present new threats to the body of research, as we could see a greater proportion of retractions being attributed to dishonest AI-generated publications. We could potentially see the number of retractions rise further this year as well.

Overall, I think that the feature of AI-generated manuscripts that include telltale signatures of the involvement of large language models only scratch the surface of a greater problem in academic dishonesty. Perhaps this is a clear case of survivorship bias; many more articles would have been weeded out in the submission or peer review stages, or retracted, but we do not really know until the statistics for 2024 are shown. I still believe that there are peer reviewers, editors, and publishers that enforce a rigourous review process to ensure reporting standards and integrity, and there are journals out there that strive for well-founded quality research.

But the presence of such journals that somehow allow AI-generated articles to be published spoils the overall image of academia, and does indeed bring a sour taste to academics, who have dedicated a significant proportion of their lives to further understanding in their respective fields of research. What is true, though, is that this phenomenon has definitely drawn more scrutiny to AI-generated manuscripts and images, and the fact that people, even those who might not be involved in academia at all, have called these publishers and journals out, brings some optimism in the fight against AI-generated manuscripts, lazy research, and this class of academic dishonesty.

In any case though, this phenomenon could have been prevented at any point in the process from writing to publication. The very fact that these AI-generated manuscripts are allowed to be published in journals, and even persist as searchable articles on Google Scholar for instance, is an indictment on what the respective publishers, peer reviewers (if they are real), and authors truly prioritise over academic integrity.

Afterword

This essay, or more accurately, a rant, is not really related to language nor linguistics, but concerns a wider area of academia. And as I rely on published articles for my essays, I felt the importance of discussing this very topic. Furthermore, I have a background in science, which also hinges on published articles when it comes to communicating and synthesising findings. Seeing how such generated papers make their way into publication, it really hit on a personal level.

Admittedly, and perhaps, ironically, I have used ChatGPT before, in exploring its capabilities in creating its own constructed language. However, I have made it clear that the use of ChatGPT was only restricted to that purpose. At no point was it used for commentary and reflections. Nor has ChatGPT been used in writing any of my essays. I really enjoy the process of learning, reading, and synthesising topics in languages and linguistics on here, and I would never want this process to be replaced by large language models.

You may have noticed a significant gap between my first exploration in ChatGPT and this rant. To be honest, I grew less interested in using it in creating a constructed language, and with growing controversies surrounding ChatGPT and OpenAI, I cannot in good faith get back to this exploration. And so, I will be discontinuing the post series on “AI-Generated Conlang”, which has lasted a grand total of one whole essay.

My rant might possibly draw some ire from the community of AI bros out there, but I believe I have made it clear that the current situation definitely deserves to be called out. I hope you have learned about the current controversy that is going on in academia right now, and I do apologise for this shift in focus from what I normally do on The Language Closet, and if you could pick out, my tone in writing this rant.

Pingback: It’s been a year, how is the situation now? | The Language Closet