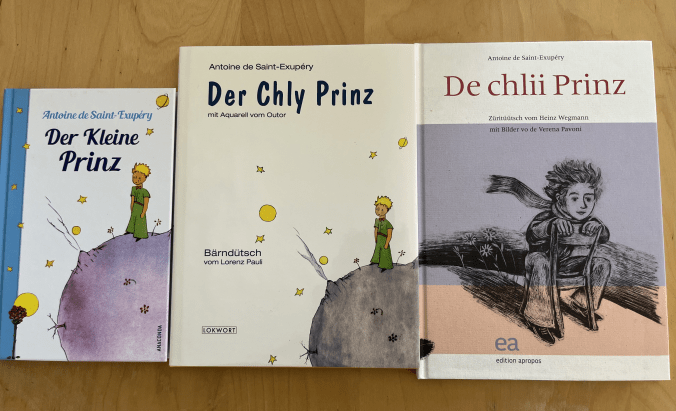

Previously, we have looked at a variety of Swiss German called Züritüütsch, or Zurich German. Among my souvenirs from Switzerland, I did mention that I have a copy of The Little Prince in another Swiss German variety. Translated as Der Chly Prinz, this variety we will look at today is Bernese German, also referred to as Bärndütsch.

Bernese German is spoken in, well, Bern, the de facto capital city of Switzerland, and perhaps in other regions of the Canton of Bern. Interestingly, Bernese German can also be found in particular regions of Indiana over in the United States, including some Old Order Amish settlements there. Like Zurich German, there are different variants of Bernese German depending on geographical region, but as the Canton and the city became better connected by various transport means, these variants have more or less converged in some manner. These variants include the one spoken in the city of Bern, city of Biel, Northern and Southern regions of the Canton of Bern, and the Bernese Highlands. Nevertheless, it is still among the most commonly spoken variants of Swiss German with perhaps around a million speakers.

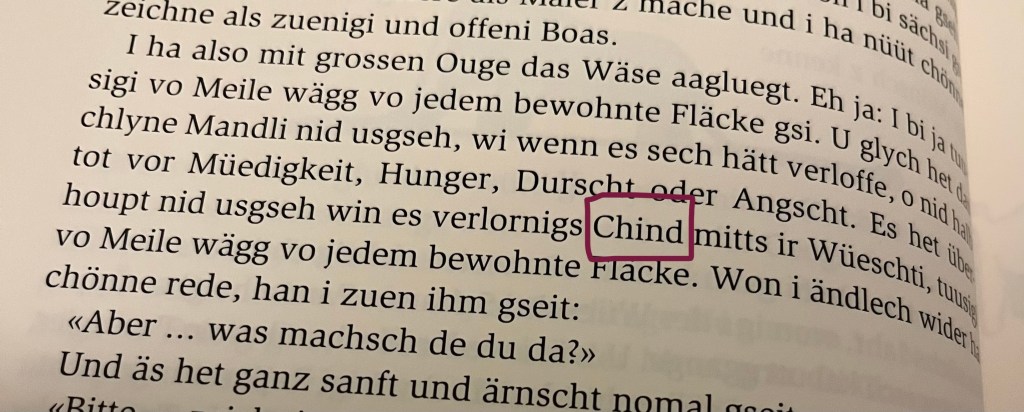

Written Bernese German, at least judging by Der Chly Prinz, seems to follow a bit closer to the Dieth-Schreibung we covered in Zurich German. Here, the d and z are written as separate words, as in d Blueme (the flower) and für sechs s z merke (to remember it). One prominent difference I could find is the lack of the accent-grave e in Bernese German, in contrast to Zurich German, perhaps because the phonologies are different and does not necessitate such a letter in Bernese German.

However, it is also important to note that there are at least two different identified orthographies used in Bernese German; there is one used for ‘older’ publications and writing, and one used for ‘newer’ ones. Like in Zurich German, neither is standard. The ‘older’ orthography emulates the Standard German one more closely, and examples include some novels by Bernese German writers. This orthography is referred to as Bärndütschi Schrybwys, by writer Werner Marti, of which, the most condensed version could be found here in German. The ‘newer’ one is the Dieth-Schreibung we mentioned in the post covering Zurich German.

Another interesting pattern I could see is the use of the letter y in places where we would otherwise expect a long /i/ sound often denoted by ie in Standard High German, and maybe a ii in Zurich German. Sometimes, this is also in place of the sound denoted by ei in Standard High German as well, such as Zyt in Bernese German compared to Zurich German Ziit, and Standard High German Zeit (time). It turns out that Bernese German shortens many of these high vowels in comparison to the other High Alemannic dialects like Zurich German. This gives words like Lüt and lut in Bernese German, in contrast to Lüüt and luut in Zurich German (and Leute, ‘people’, and laut, ‘loud’, in Standard High German).

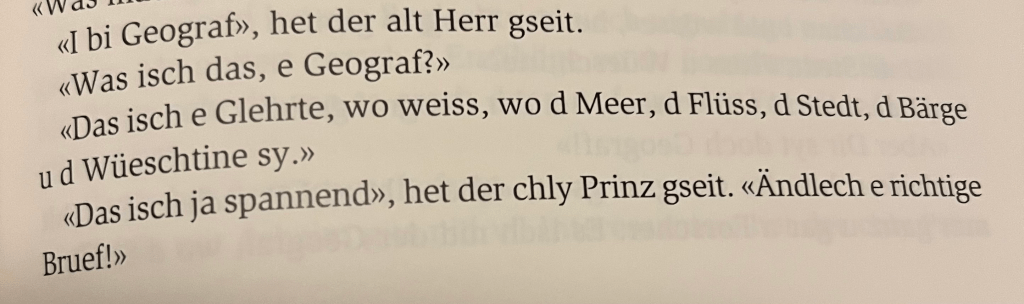

One other phonological difference is the pronunciation of nd as ng, a phenomenon referred to as velarisation. In some orthographies, this change is reflected, such as Ching, compared to Standard High German Kind (child). However, the book I have still rendered this as Chind, so perhaps this would have been vocalised as Ching anyway by the Bernese German speaker.

Additionally, some /l/ sounds sound like the ‘w’ sound in English, a sound change called “l-vocalisation”. This makes words like Halle (hall) become Hauue in Bernese German. Once again, I could not really find such examples in Der Chly Prinz, as Krallen (claws) are translated as Chralle, although l-vocalisation could perhaps occur in that word. Maybe the orthography used in Der Chly Prinz deviates a bit from the other orthographies used to demonstrate these phonological differences. Nevertheless, I could still do a side-by-side comparison between Bernese German and Standard High German and Zurich German to try to spot some patterns where the Swiss German dialects would deviate from Standard High German.

There is also a difference in the use of the “Polite you” pronoun between Bernese German and Standard High German. In Standard High German, we are familiar with the pronoun Sie, formed using the plural third person pronoun. But in Bernese German, this is formed using the plural second person pronoun as if it were in French. In Bernese German, this is usually written as Dihr or Dir, and may be contracted to ‘er. This may have also contributed to the greeting Grüessech, the Bernese German form of the greeting Grüezi. This greeting, translated as ‘[God] greets you’, is formed from the constituents [Gott] grüsse Euch, and has undergone several sound changes over time, diverging between the Swiss German-speaking regions and cantons.

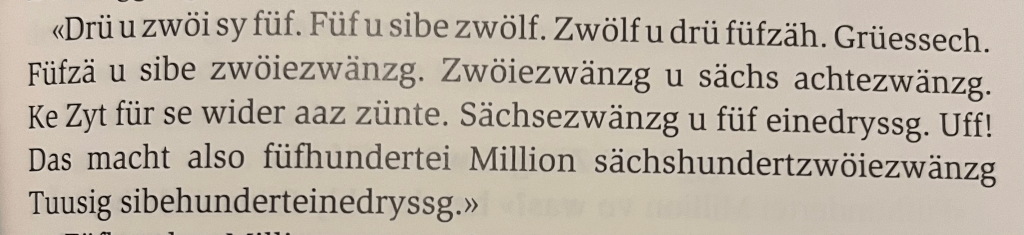

Chapter 13 of Der Chly Prinz / Der Kleine Prinz offers a great comparison in numbers used in Bernese German and Standard High German, where I could find patterns in where words for certain numbers would deviate from the Standard High German counterparts. Bernese German uses different forms for the numerals ‘2’ and ‘3’ by grammatical gender, and uses the neuter word when referring to numerals by themselves.

| Grammatical gender | 2 | 3 |

| Masculine | zwee | drei |

| Feminine | zwo | drei |

| Neuter | zwöi | drü |

Like in Zurich German, the und in numbers are reduced to e. But as their own word, in Bernese German, und is u. Similarly, the multiples of 10 end in –zg or -sg instead of -zig or -ßig. Other reductions observed in Zurich German are also seen here in Bernese German, such as the commonly-found participle prefix g-, as in ggange (gone).

While I have yet to encounter spoken Bernese German in person, partially because I have not travelled to Bern yet, there is a word that has probably “defined” or distinguished Bernese German as a unique dialect of Swiss German. This word is Äuä. From what I could find online, äuä, when used as a particle, conveys a connotation of disbelief, like “no way!”, although this meaning can change based on the tone or emphasis in which it is said. But when used in a full sentence, it conveys a connotation of the speaker being ‘quite certain’ about something. Of course, there are other words that are special to Bernese German, as introduced by 20 Minuten (in German), such as the word geng or gäng to mean ‘always’ instead of immer in Standard German.

This is pretty much what I have gathered during my reading and introduction to Bernese German. Perhaps when I visit Bern at some point, I could hear some of this in person, and perhaps pick up more spoken patterns there, as I somewhat have experienced during my time in Zurich for Zurich German. But I hope you have learned a thing or two about yet another variety of Swiss German, and perhaps we will look at more variants of German at some point in the future.