Recently, I went on a trip to Zurich for a convention, and decided to stay a day longer to explore as much of the Altstadt and the Limmat as I could. Naturally, I explored the local bookstores in search of a particular variant of German that I have mentioned on here several times before. Swiss German, commonly known as Schwiizerdütsch, is widely spoken in Switzerland and neighbouring Liechtenstein, and there are different dialects spoken in specific cantons in Switzerland.

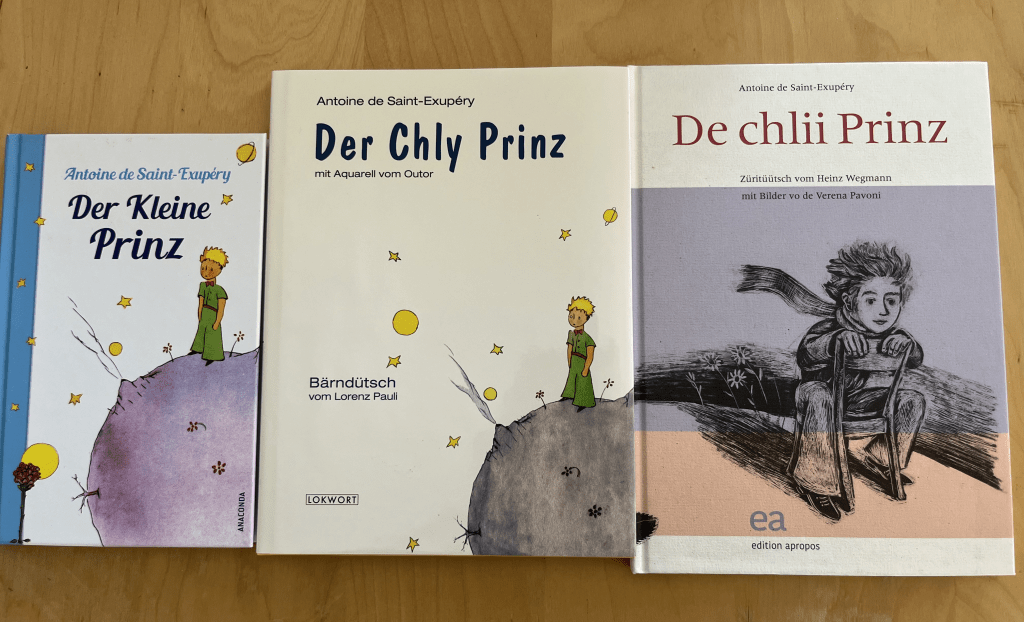

Fortunately, I was able to find a bookstore that had The Little Prince in Swiss German, but in two of these dialects. As far as I can recall, there could be a dozen or so variants of Swiss German, and the two they had in stock when I visited were the Zurich German and the Bernese German translations. And this being Switzerland, these might be the most expensive copies of The Little Prince I have bought so far for my collection.

So today, I want to talk about a particular variant of Swiss German, this time being the variant spoken in the Canton of Zurich. Called Züritüütsch, this is among the most commonly spoken variants of Swiss German, with more than a million speakers. Historically, or at least, traditionally, there are six sub-variants of Zurich German, from the sub-variant spoken in Winterthur, to, of course, the sub-variant spoken in the city center. As commuting between the different areas of the Canton of Zurich became easier and more convenient, these sub-variants have homogenised along with increasing connectivity.

Despite what you see in De chlii Prinz, there is technically no standardised orthography for Zurich German; like many Swiss German varieties, Zurich German is predominantly spoken. It does try, in a limited capacity, to follow the orthography proposed by the Swiss linguist Eugen Dieth in the 1930s, called Schwyzertütschi Dialäktschrift, also known as Dieth-Schreibung. As he specialised in the field of phonetics, his orthography aimed to provide a means of phonetic transcription of the Swiss German dialects using letters, including some diacritics, that one would find on a typewriter or a keyboard.

One of these features is the use of the accent grave on the letter ‘e’, something you would expect to find more often in languages like French. This is generally used to transcribe the [ɛ] sound, a sound that already exists in Standard High German. This distinguishes from the Zurich German ‘e’, which normally represents the [e] sound. As such, hèèr and Heer may sound similar, but differ in the vowel quality and do mean different things. The former means ‘from’, while the latter means ‘army’.

However, other letters used in Dieth’s transcription like ǜ are not used. Furthermore, while the apostrophe is used in Dieth-Schreibung, he advised against using it to emphasise omissions, a guideline that is generally broken when I read the Zurich German translation of The Little Prince. In a way, Dieth-Schreibung seems to be weakly applied to write Zurich German, at least from the rough guide I have read when I compared it with what is written in the novel.

While examples of applied Dieth-Schreibung generally are in Bernese German, a different Swiss German dialect, one accessible source I could find for Zurich German is here, although, once again, is not really closely followed in the novel. Thus my impression of written Zurich German was the fusion of Standard High German orthography with certain rules or characters in Dieth-Schreibung.

Like many other German dialects, Zurich German operates on a system of fortis and lenis consonants. This refers to the pronunciation of consonants either in a tense or a lax manner, and is distinct from the voicing system as fortis and lenis do not involve the vibration of the vocal cords. Sometimes, this fortis forms, transcribed as /k/, /t/, /p/ etc. may be aspirated. This fortis and lenis can be distinguished by consonant length in Zurich German as well, with the fortis consonants like /k/, /t/, and /p/ being the longer counterparts.

As I read the Zurich German version with the Standard High German version on the side, I was able to identify some patterns in which words deviate from the Standard High German form. Zrugg is the Zurich German way to transcribe Zurück, or the German word for ‘back’. In many participles, the ‘ge-‘ prefix is generally reduced to ‘g-‘, as in the comparison between words like gesagt in Standard High German and gsäit in Zurich German for the participle ‘said’, and gefragt in Standard High German versus gfrööget in Zurich German for the participle ‘asked’.

This similar reduction is seen in the prefix ‘be-‘, reduced to ‘b-‘ in Zurich German transcriptions. However, exceptions seem to exist, as the Zurich German word for bestellen (verb to order) is bstele, but Befehl (command) is written the same in both Zurich German and Standard High German.

Other cases of such reductions could also be seen in the multiples of 10 in Zurich German numbers. For example, 20 is zwanzig in Standard High German, and zwänzg in Zurich German, and 30 is dreißig in Standard High German, and drissg or driissg in Zurich German. And when making up numbers like 53, the “und” part in Standard High German’s dreiundfünfzig is written as just “e” in Zurich German, as in drüüefüfzg. You could find this in Chapter 23 of De chlii Prinz or Der Kleine Prinz.

Similarly, the particle zu tends to be reduced to z’ in some cases. For example, compare this sentence in Chapter 15 of Der Kleine Prinz with its Zurich German counterpart:

- Ebenso wie ein Forscher, der zu viel trinkt.

- Und übrigens au en Forscher wo z’vil trinkt.

- Just like a researcher who drinks too much.

The relative clause particle is different as well, as in the example above, one of the Standard High German words to express this is der (which differs by grammatical gender), while the Zurich German one uses wo, which translates to ‘where’. In fact, relative pronouns are generally not used for such a purpose in Zurich German.

There are definitely many Zurich German expressions or colloquialisms I have yet to mention, but this was pretty much all I could pick up in the couple days I spent in Zurich, and the novel I bought. But I hope it is a brief but informative introduction to how Zurich German is written, and how it differs from Standard High German. Soon, we will cover the other Swiss German translation I got my hands on — Bernese German.