Simplified Chinese characters are probably what almost every learner of Mandarin Chinese would practice writing. Used predominantly in China, Singapore, and to a lesser extent, Malaysia, this writing system is used by more than a billion people, and does seem like a recent thing. But the history of simplified Chinese characters stretches way further than this. predating the adoption of simplified Chinese characters in China by centuries.

Early examples of simplified Chinese could be seen as far back as the Qin dynasty (221 BCE – 206 BCE), where cursive Chinese was primarily used as inspiration for simplification. Some strokes would be reduced, or omitted, resulting in character variants that deviate from Classical Chinese characters. But it was not until the dying days of the Qing dynasty (1644 – 1911) when a movement to simplify Chinese characters would start to gain traction. People saw the need to ditch traditional Chinese characters, as it was blamed for many problems from economy to literacy. Within the Kuomintang, there were discussions surrounding character simplification, with the first batch of simplified characters was introduced in 1935, contributed primarily by Qian Xuantong.

But what we know about simplified Chinese today is its association with the People’s Republic of China. Following the takeover of Mainland China by Mao Zedong’s Chinese Communist Party, further work of character simplification was undertaken by them. We have heard of the Scheme of Simplified Chinese Characters in 1956, and stabilisation in 1964, which saw hundreds of characters like 機 and 龜 being simplified to 机 and 龟 respectively. Many of these simplifications drastically reduced the number of strokes for each character affected, which is said to aid learning and gaining literacy. But what many would overlook is the directive for “further simplification to improve literacy”, which entailed reducing the number of strokes needed such that most commonly used characters would need fewer than 10 strokes to write per character.

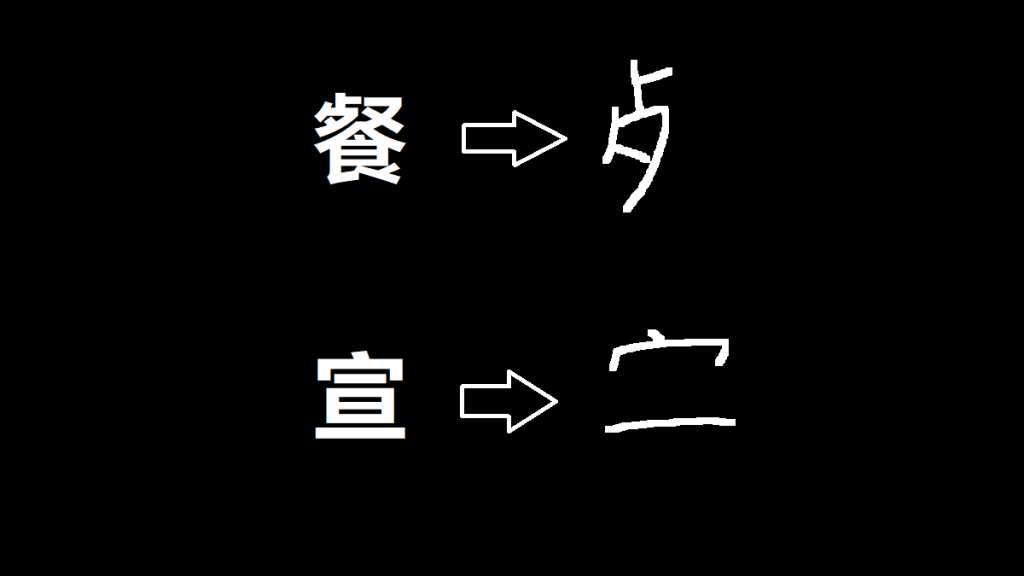

Released in 1977, the Second Round of Simplified Chinese Characters (draft), or 第二次汉字简化方案(草案), abbreviated to 二简字, consisted of two collections of affected characters — the first contained 248 characters for further simplification, and the second contained 605. This made a total of 853 affected characters. With this simplification, characters like 餐 would be reduced to 歺, 蛋 reduced to 旦, and even family names like 蔡 reduced to 𦬁.

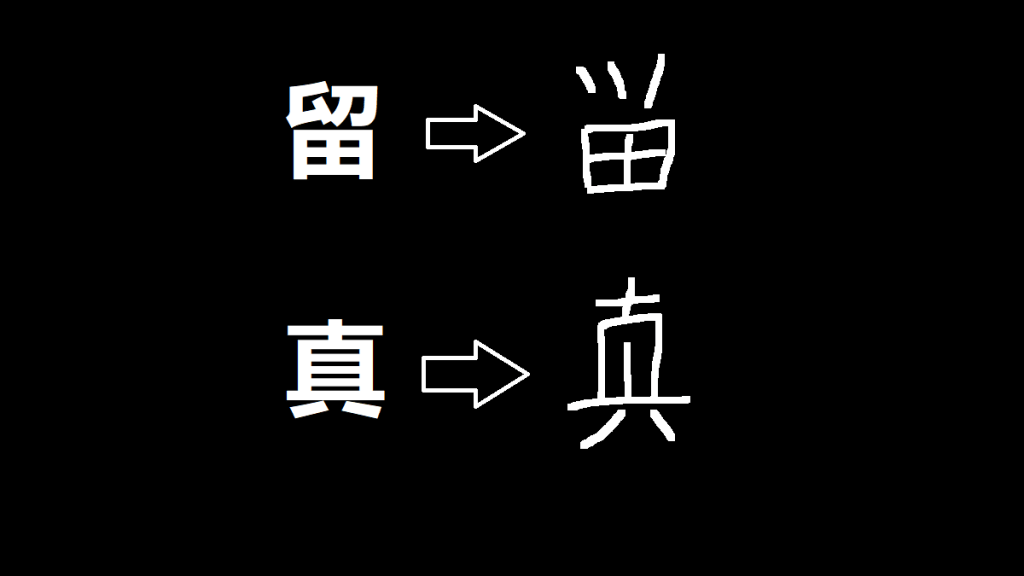

So how were these characters simplified? There were at least 5 general patterns of simplification, which were applied for the preceding first round of simplification several years prior.

The first pattern is to preserve the radical, and change the phonetic component to a simpler one that still carries a similar sound. Below, we see the example where 翏 (liù) is replaced with了 (le / liǎo) for the character liào, drastically reducing the number of strokes needed to write the character. Similar parallels with simplified Chinese used today include 进, from 進, and 远, from 遠.

Sometimes, characters have entire constituents replaced by something that is “similar in meaning”. A similar pattern you might see in simplified Chinese today is the character 时, which is simplified from 時. Occasionally, this would still largely preserve the meaning of the original character, pronunciation, and the replaced components, albeit much more reduced than its predecessors in terms of complexity.

Or you could just omit entire components of a character, but done so in a way that ambiguity is not created. However, some important semantic parts of a character can be dropped, which detaches the simplified character from its semantic components (like radical for ‘food’). Parallels used today include 声, simplified from 聲, and 电, simplified from 電.

Radicals can still be dropped nonetheless, creating characters with just the phonetic component. Occasionally, these can be identical to existing characters, creating some mergers between two potentially unrelated words. Examples of this include 稀 (xī, “rare”) being simplified to 希 (xī, “hope”), and 蝌蚪 (kēdǒu, “tadpole”) being simplified to 科斗 (kēdǒu, individually, “section” and “fight”). This way, previously distinct characters would be merged into one, with a largely similar or identical pronunciation, but with different meanings, usages, and ways to form compound words with.

When taken to a relative extreme, an entire character could just be replaced with a similar-sounding character. This is called 字形假借, or phonetic loans. It plays on the nature of Chinese words having many homophones, especially when individual syllables are considered. Perhaps the most prominent example of this is the simplification of 蛋 (dàn, “egg”) to 旦 (dàn, “day” as in 元旦 “New Year’s Day”).

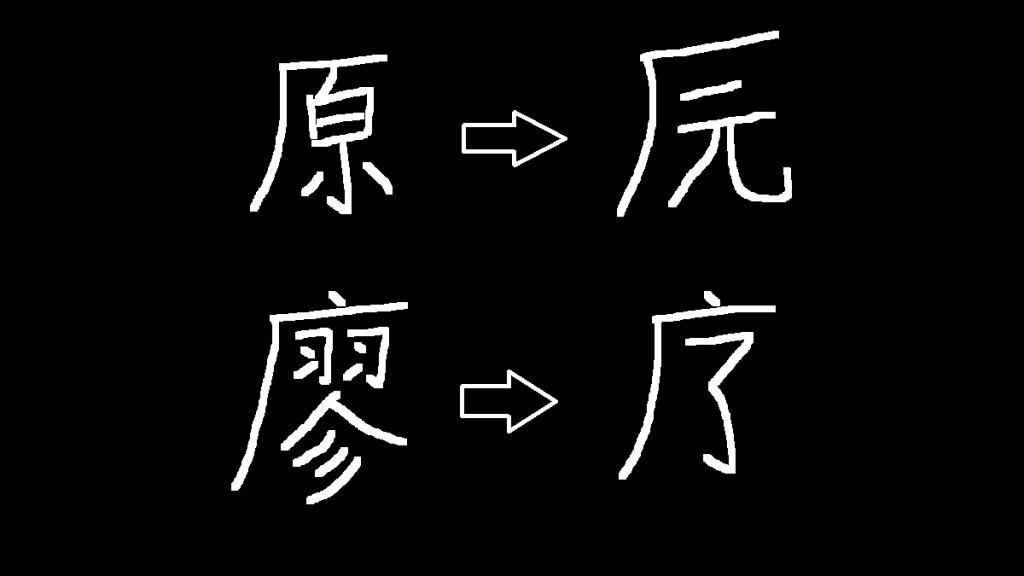

Lastly, partial “structural changes” could be made to a component of a character, but still largely preserves the overall shape of the character. Sometimes, unrelated replacements would be used, but are inspired by cursive Chinese. Examples of this include the ones below. Similar characters affected in the first round of simplification included 汉, from 漢, 欢, from 歡, and 学, from 學.

But unlike the first scheme, this one was received poorly. So much so that in 1978, publishers of textbooks and newspapers were asked to stop using this second simplification. And it was not until 1986 when the Second Scheme was officially retracted by the State Council. However, that was not the end of this reform. A final version of the 1964 character list was published later that year, showing minor changes to some characters such as 覆 and 像 used today.

However, the exact reasons why the Second Scheme failed were not really transparent. Some have attributed it to the Cultural Revolution, which ended a couple of years before. Intellectuals including linguists and trained experts would have been expelled during this period, and that this subsequent scheme would have taken place without consultation from linguists and expert opinion.

Other reasons given was the large number of characters this scheme affected, some internal politics, or that the need to maintain internal consistency and redundancy was recognised. But as many documents surrounding the Second Scheme, especially the reasons for retraction, remain classified and controversial, these theories for the failure of the Second Scheme remain as educated guesses at best.

Even after the retraction, some second-simplified characters are still used in informal situations today. Some restaurants could still use signs saying 歺厅 instead of 餐厅, and some second-simplified characters are still supported by the Unicode to this day. Even as the focus of language planning has shifted towards standardisation and regulation of existing characters, future changes and potential reform are still a possibility, and who knows if decades in the future, the Chinese language could once again, look very different from what we are used to today.

Afterword

Well, this has been yet another dive into the Mandarin Chinese rabbit hole, but there are still so many features and history of some aspects of written Chinese that many of us are not really aware about. As I write, I uncover yet more obscure simplifications of Chinese characters that I am pretty sure even fewer people are aware about. Nevertheless, it has been fun covering topics like this, and hopefully you would see even more topics like this.

Pingback: VDG 2025-07-12 Post-Mortem (List of Topics) – VDG Topics