Previously, we covered Mainland Chinese Braille, which works pretty similar to a syllabary, but interestingly lacked tone markers on a majority of cases. Today, we will look at another braille system used in China to read and write Mandarin Chinese. Designed and developed in the 1970s, and approved by the State Language Committee of the People’s Republic of China in 1988 for promotion, this system is used in parallel with the braille system we introduced previously. This system is called the Two-cell Chinese Braille system, or 汉语双拼盲文.

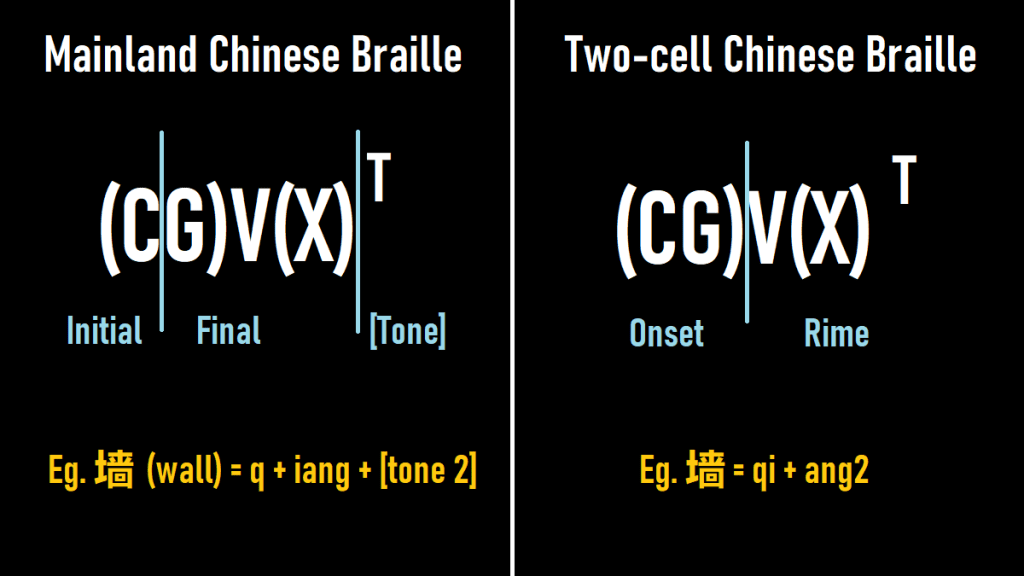

We have talked about the syllable structure of Mandarin Chinese in the previous post, and it is upon this principle that the two-cell Chinese Braille system is built. While similar to Mainland Chinese Braille in principle, how the syllables are split to form the initial and final is different. In Mainland Chinese Braille, the initial is just the consonant initial in the syllable. The final uses the glide, vowel, and the coda, while the tone, if used, is expressed using a separate cell. This makes Mainland Chinese Braille syllables have anywhere from one to three cells.

Two-cell Chinese Braille, as the name suggests, has syllables that are rendered as two braille characters, with the first character termed the “onset”, and the second character termed the “rime”. The onset consists of the consonant and glide, while the rime contains the rest, including the tone. See below for the difference in how braille characters are rendered.

However, like Mainland Chinese Braille, the two-cell Chinese Braille has ‘k’ sharing onset characters with ‘q’, ‘g’ with ‘j’, and ‘h’ and ‘x’ as these do not contrast i.e. qi exists as a possible syllable, but ki does not. Interestingly, there is a character to represent the null consonant, since a syllable containing only a rime (like an) would only otherwise have one cell.

For the onset, the consonant initial is represented by 4 dots, typically the three on the left column and the top dot on the right column. There is an exception though, as the initial “r-” is represented by ⠔.

There are three possible medial sounds or glides excluding the lack thereof, namely, the “-i-“, the “-u-” and the “-ü-“. Distinguishing these makes use of the remaining two dots in the onset cell. For instance, “-i-” has ⠐, “-u-” has ⠠, and “-ü-” has ⠰. The reason why the initial “r-” could have such a representation is, this initial only can take “-u-” as a medial, for example, in the syllable ruan. Additionally, the “z”, “c”, and “s” initials are derived from the “zh”, “ch”, and “sh” initials respectively, and are treated as if they have an “-i-” medial, and for the “zu” – “zhu” etc. counterparts, the “zu-“, “cu-“, and “su-” onsets are treated as if the “zh”, “ch”, and “sh” have an “-ü-” medial.

So, all the initial-medial combinations in the onset can be found below. Some combinations are not used, as there are some initial-medial combinations that are not used in the Chinese language.

| b- | p- | m- | f- | d- | t- | n- | l- | g- | k- | h- | zh- | ch- | sh- | r- | — |

| ⠊ | ⠦ | ⠪ | ⠖ | ⠌ | ⠎ | ⠏ | ⠇ | ⠁ | ⠅ | ⠃ | ⠉ | ⠍ | ⠋ | ⠔ | ⠾ |

| bi- | pi- | mi- | di- | ti- | ni- | li- | ji- | qi- | xi- | z- | c- | s- | y- | ||

| ⠚ | ⠶ | ⠺ | ⠜ | ⠞ | ⠟ | ⠗ | ⠑ | ⠕ | ⠓ | ⠙ | ⠝ | ⠛ | ⠒ | ||

| du- | tu- | nu- | lu- | gu- | ku- | hu- | zhu- | chu- | shu- | ru- | w- | ||||

| ⠬ | ⠮ | ⠯ | ⠧ | ⠡ | ⠥ | ⠣ | ⠩ | ⠭ | ⠫ | ⠴ | ⠢ | ||||

| nü- | lü- | ju- | qu- | xu- | zu- | cu- | su- | yu- | |||||||

| ⠿ | ⠷ | ⠱ | ⠵ | ⠳ | ⠹ | ⠽ | ⠻ | ⠲ |

The rime takes on the vowel, coda, and tone of the syllable. Like the onset, the rime also operates something like an abugida, just that instead of an inherent vowel a typical abugida letter would have, this one has an inherent tone. Here, tones are determined by modifying the bottom two dots. The inherent tone has no raised dots, and represents the falling tone and neutral tone. If the bottom left one is raised, it represents the level tone. If the bottom right dot is raised, then the rime has a rising tone. Both bottom dots being raised would indicate the third tone, or the ‘dipping’ tone.

Exceptions do exist, especially for the rime ei, which is written as ⠌ for the falling and neutral tones. As the bottom left dot is already used to write the rime, the tone is indicated using the two bottom right dots instead. Level tone is ⠜, rising tone is ⠬, and dipping tone is ⠼. Additional exceptions also include the writing of the er rime, which is written as the syllable ra, as the sound does not exist in Mandarin. Additionally, to represent the erhua modification to some words, ⠔ is written at the end of the word, and a hyphenated version ⠔⠤ is used for within a word to prevent confusion with an onset r sound in the following syllable.

However, there are still some syllables that are not really accounted for. At least from what we are familiar with. Syllables like jin, dun, and qiong, there are some workarounds that have to be done, and these involve onset-rime combinations that are different from the pinyin counterparts we are familiar with.

- jin (or the -in final) is written as if it is jien i.e. ji + en cells. Similarly, syllables like qing (-ing final) are written like qi + eng

- dun (or the -un final) is written like du + en. Similarly, syllables like kong (-ong final) are written like ku + eng

- qiong (or the yong syllable/-iong final) is written like qu + eng

And so, here are all the rimes!

| -ì, -ù, -ǜ | -à | -è, -ò | -ài | -èi | -ào | -òu | -àn | -èn | -àng | -èng | èr |

| ⠃ | ⠚ | ⠊ | ⠛ | ⠌ | ⠓ | ⠉ | ⠋ | ⠁ | ⠙ | ⠑ | ⠔⠚ |

| -ī, -ū, -ǖ | -ā | -ē, -ō | -āi | -ēi | -āo | -ōu | -ān | -ēn | -āng | -ēng | ēr |

| ⠇ | ⠞ | ⠎ | ⠟ | ⠜ | ⠗ | ⠍ | ⠏ | ⠅ | ⠝ | ⠕ | ⠔⠞ |

| -í, -ú, -ǘ | -á | -é, -ó | -ái | -éi | -áo | -óu | -án | -én | -áng | -éng | ér |

| ⠣ | ⠺ | ⠪ | ⠻ | ⠬ | ⠳ | ⠩ | ⠫ | ⠡ | ⠹ | ⠱ | ⠔⠺ |

| -ǐ, -ǔ, -ǚ | -ǎ | -ě, -ǒ | -ǎi | -ěi | -ǎo | -ǒu | -ǎn | -ěn | -ǎng | -ěng | ěr |

| ⠧ | ⠾ | ⠮ | ⠿ | ⠼ | ⠷ | ⠭ | ⠯ | ⠥ | ⠽ | ⠵ | ⠔⠾ |

While punctuation largely follows the same convention as the Mainland Chinese braille system introduced previously, along with numbers, there are some abbreviations worth mentioning which may just disrupt the nice two-cell system that this braille system has.

Affected characters typically include the commonly used words and particles, such as 的 (de), 在 (zài), 和 (hé), 是 (shì), and 有 (yǒu). In some cases, these are shortened to one cell typically containing the corresponding onset like ⠟ for 你 (nǐ), ⠌ for 的, and ⠋ for 是 (but ⠖ if it is a suffix). Others could be abbreviated to the rime instead, as with the case of ⠭ for 有 (but 没有 méi yǒu is written as ⠪⠒, literally ‘m y’), ⠓ for 要 (yào), ⠞ for 他 (tā), ⠣ for 时 (shí) and ⠮ for 也 (yě). 们 (men) is written as ⠂instead, since the corresponding onset ‘m’ is used for 没. Other patterns include ⠱ for 就 (jìu).

But what happens when an ambiguity would arise nonetheless, like with 他, 她, and 它, which are all pronounced the same? This is when homophone distinguishers are added to the start of the syllable in question. So 她 could be written as ⠈⠎⠞, and 它 would be written as ⠐⠎⠞. But to distinguish the grammatical particles 的, 地, and 得, all pronounced de, a different pattern is used. They are written as ⠌, ⠜, and ⠌⠔ respectively.

Lastly, sometimes, Chinese speech can be contracted, resulting in some words that could still be unambiguously written in normal Chinese, but present ambiguity in Chinese braille. Here, the cell ⠘ is used before the omitted syllable to indicate that a syllable is dropped when contraction occurs. ⠼ is used as a number indicator, but it is also used in reduplication of both syllables and words. It is attached after a word to indicate a syllable is reduplicated, and when it is used alone, it can reduplicate an entire word.

And there we have it, the two-cell Chinese braille system. Personally, if I were to choose between the two systems used to write Chinese in braille, I would pick Mainland Chinese braille. Not only is it simpler, there are fewer combinations of initials and finals to remember, and tone may not be necessarily needed to give the reader an idea of what the word is. But I would like to hear from you, would you prefer Mainland Chinese braille, or two-cell Chinese braille?