For most of us today, we read and write our languages in various writing systems — some use alphabets, some use syllabaries, and some decide, why not, just use a bunch of them together. Despite the ubiquity and importance of writing in various societies today, most languages across the world are predominantly only spoken, with no writing system prior to introduction of writing systems like Latin and Arabic. Recording information and communication is important; to survive, one must be able to know how to navigate, recall their genealogy, and things like these. And so, some of us around the world choose to develop writing systems to help record this information and communicate this information.

Across the world, we see different methods of recording information in addition to the conventional writing systems we have found throughout history. In Pre-Columbian America, the Maya were known to develop the Maya hieroglyphs, a writing system that surprisingly, actually works rather similarly to Japanese. The Inca, on the other hand, are not really associated with developing a writing system. Instead, they have a complex knot system called quipu, but the technique of encoding and decoding these knots, however, remains to be rediscovered.

In the Polynesian peoples, various writing systems exist, including the undeciphered Rongorongo found in Easter Island. On some places like Tonga and Hawaii, petroglyphs have been discovered that seem to encode some sort of information. While not considered to be writing, it could be likely that these could at least represent graphical mnemonics on important aspects of Polynesian culture, from folklore, to maritime navigation.

But now, we come to Australia. The Aboriginal Australian peoples have an extensive history stretching back many millennia, with some estimates putting the first settlement as far back as 65 000 years ago. With over 300 languages spoken on the Australian mainland and the Torres Strait Islands, it definitely came as a surprise to learn that none of these have their own writing system. The only texts I could find concerning a considerable number of these languages are largely developed after European contact, almost all of them using the Latin alphabet with their own orthographical systems. Pouring over information on the web, many sources said that prior to European contact, the Aboriginal Australian peoples did not develop a writing system. It led me to ask myself this question. Why?

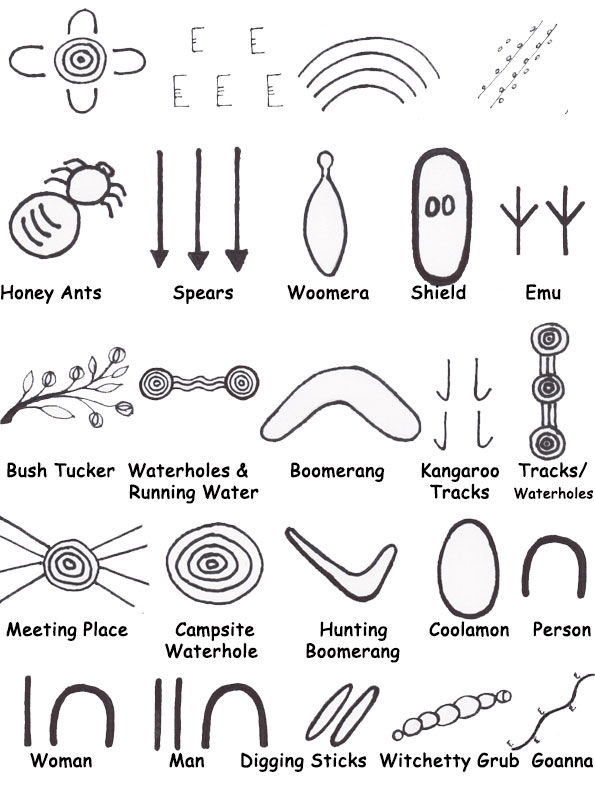

Writing could be done using different techniques, from inking a substrate with some sort of pigment, or inscribing of glyphs into a substrate, usually wood or stone, using a carving instrument. The Aboriginal Australian peoples are known for developing various motifs, each with its own symbolism attached. Looking at pictures of rock paintings and art, it does seem that they have developed techniques to manufacture various pigments to be painted on substrates like rock. And unlike some media like leaves, these last for a rather long time. This confused me even further, as there was an availability of pigments to function as ink in writing. Thus, the scarcity of media to develop writing systems cannot be the answer to this question.

Maybe this would have a more cultural reason. Aboriginal Australian cultures predominantly rely on oral history, but that sounds like an immense amount of information to recall and pass down, especially after factoring in information that is crucial for survival in Australia, like navigation, food sources, tools, kinships, genealogy, and intra- and inter-ethnic politics, relations, and trade. Without writing, recording this information into memory would necessitate alternative means. This was when I found an interesting article written by Reser et al. (2021) and published in the PLoS One Journal, which goes into detail on these Aboriginal Australian memorisation techniques.

From the article, this crucial information is mostly embedded in art. Artwork, even those found in tools, have symbolic and geometric patterns that encode detailed information of tribal interest, something most of us would be oblivious to and not realise. Traditional songs also contain these types of information, which becomes oral history.

Now, what happens when an Aboriginal Australian needs to learn new information beyond the scope of traditional song? The usual method was to construct a story that incorporates aspects of the ecology and physical geography of the local area, building in further details like numbers and chronology of events. And so, most of these information we would typically record in writing would have been memorised using these location-based methods and song.

However, it would also be argued that writing is also meant to be a means of communication in addition to recording and storing information. Memorisation techniques could substitute for recording and storing information, but what about communication?

While doing research to find answers to this pressing question, I came across pictures of message sticks. These message sticks are typically fashioned out of wood, with carvings or motifs engraved on all sides. This is a system of public communication used throughout Aboriginal Australian people groups, used to reinforce verbal messages. With this, messages could be conveyed across different Aboriginal nations, clans, groups, and even languages. Considering that there are around 300 Aboriginal languages spoken on Australia, this seemed to make for a rather effective communication system.

While message sticks have been the subject of anthropological study in the 1880s, there has been little publication on them since. Many message sticks remain to be deciphered, their motifs to be understood, and its function in Aboriginal Australian society to be uncovered. Nevertheless, its use in diplomacy and trade has been observed and recorded by various anthropologists in the early 20th century. The most prominent use of the message stick in recent times was in 2018, where Yolŋu leaders presented Prince Charles (now King Charles III) with a message stick to convey a “formal request for the royal representative to intervene on behalf of Yolŋu people in treaty negotiations with the Australian federal government” (Kelly, 2020).

The message stick system raises further questions — could they perhaps be considered a writing system, or at least, a proto-writing system? This debate started back in the 1880s, where early conjectures suggested that the message sticks were a substitute for writing, while others thought they could be a first step to development of a writing system. If it is a writing system, anthropologists and linguists suggest that this would lean towards a semasiographic system, a non-phonetic based technique that could be similar to say, contemporary systems like emoji and mathematical notation. This way, phonetic differences between language groups could be circumvented to facilitate communication between two or more different languages.

Perhaps I was asking the wrong question. A more appropriate question would have been, what is the purpose of writing, and how different does Australia do it compared to us? The Aboriginal Australian people groups could have their own form of writing, but they do it in extremely different ways from our preconceptions of writing. Art, patterns, motifs, these could all have mnemonics and symbolisms embedded into them, unnoticed to the untrained eye.

Further reading

Reser D, Simmons M, Johns E, Ghaly A, Quayle M, et al. (2021) Australian Aboriginal techniques for memorization: Translation into a medical and allied health education setting. PLOS ONE 16(5): e0251710. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0251710.

Kelly, P. (2020). Australian message sticks: Old questions, new directions. Journal of Material Culture, 25(2): 133–152. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359183519858375.