To say the languages of what is today China, or the People’s Republic of China, exert a strong influence on other languages in the region, is an understatement. Loanwords have entered languages such as Uyghur, Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese, and writing systems based on Chinese have entered use in Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, and perhaps a bunch of other languages that might have been wiped out by other empires that existed across history. Today, we will look at one such writing system, once used in writing for a language spoken what is today China, but extinct for centuries.

If you are familiar with the Chinese script, the Tangut script kind of looks like blocks of pure gibberish. While Tangut shares elements of its writing system with Chinese, such as characters representing one syllable each, a shared set of stroke types (perhaps except for the oblique bend stroke exclusive to Tangut), and how both systems are in part logographic. But this is where Tangut starts to deviate from Chinese. It has been remarked as one of the least convenient writing systems to work with, with no character having fewer than 4 strokes, and many having anywhere from a dozen to twenty strokes per character. With more than 5,800 identified characters to work with, and Tangut being extinct for centuries at this point, decoding Tangut would pose an immense challenge to work with.

After the Western Xia dynasty was wiped out by the Mongol Empire in 1227, the Tangut language survived in obscurity until its extinction some time in the 16th century. What we were left to work with were fragments of Tangut literature, and some rhyming dictionaries that provided a key to what Tangut could have sounded like.

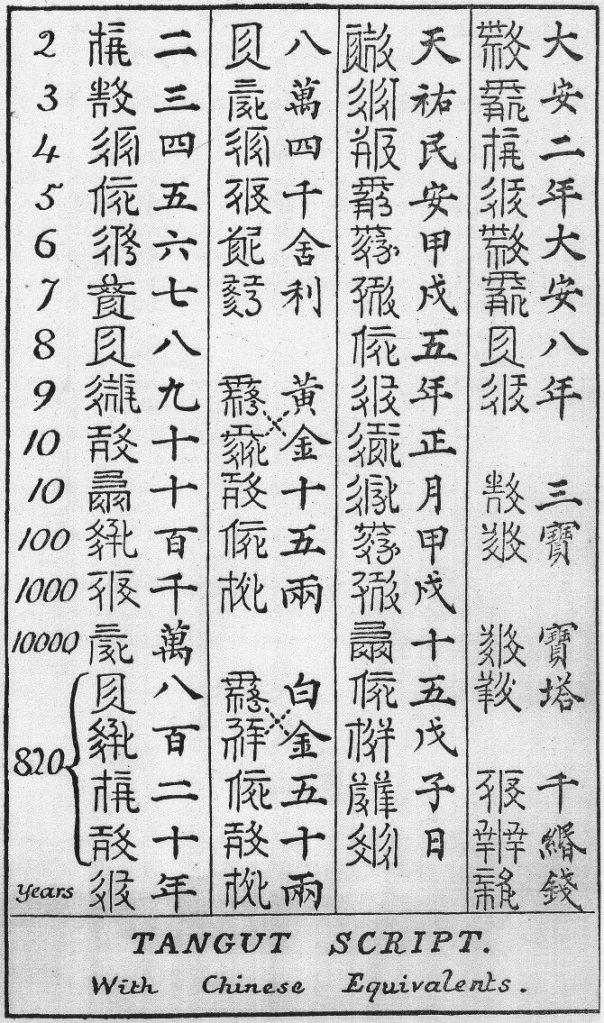

The Tangut language was rediscovered by various scholars in the 19th and 20th century, and soon, efforts to decipher the relatively unknown writing system were abound. Bilingual Chinese-Tangut inscriptions, coins, books, and other media proved great help in understanding the relationship between Tangut and its Chinese translation. Perhaps the most significant contribution in this field could be credited to Russian scholar Nikolai Aleksandrovich Nevsky, who helped further knowledge in Tangut grammatical particles, and compiled the first Tangut dictionary. This made it possible, for the first time in centuries, to read, understand, and interpret Tangut texts.

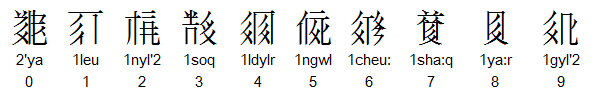

Like Chinese, Tangut had a tonal system. But it was a relatively simpler system. With 2 tones, flat and rising, this was far simpler than the 4 in Chinese, 6 or 7 in Hokkien, and 9 in Cantonese. However, Tangut had three types of vowels. Vowels could be normal, tense, or retroflex. In total, this gives Tangut a total of around a hundred different syllable codas, given that its syllable structure was CV.

What is remarkable about Tangut was, despite each character appearing to be a mash of strokes that are seemingly randomly put together, some individual elements within characters could be identified. This is what we call “radicals”. In Chinese, there are 214 identified radicals, also called Kangxi radicals. But in Tangut, some 400 or so are identified, according to the Radical Index to Li Fanwen’s Tangut Dictionary (1997). With as many as 16 strokes per radical, Tangut radicals generally appear distinct from those in Chinese, although some familiar ones could pop up now and then.

Tangut is not pictographic. The simplest of Tangut characters do not resemble the meaning they are supposed to represent, not even numbers. This would suggest that how characters were formed in Tangut took more of a semantic or phonetic approach. After all, complex Chinese characters are generally formed using a semantic component, and a phonetic component. These components contribute its own meaning and sound components respectively. But Tangut takes things differently — A complex Tangut character has a component that contributes the meaning or sound of another character containing it, and it could be different in every appearance. For example, the character for “mud” compounds the character for “water” and character for “soil”. But the character for “water” contains a component that marks it as “water”, and thus that radical is used together with the entirety of the word “soil” to give “mud”.

Some characters can also look almost entirely identical — the Tangut characters for “toe” and “finger” have the same components, but have the left and right portions switched around in their respective complex characters.

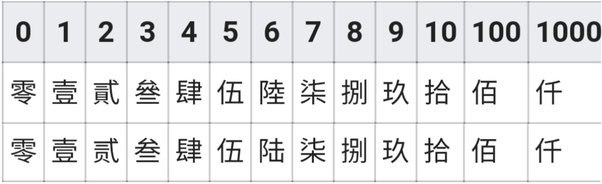

When it comes to number characters for Tangut, things get complicated. Before we get to that, Chinese numerals are relatively simple. Each character is written with relatively few strokes, even up to “hundred”, “thousand”, and “trillion”. The characters for “ten thousand” and “one hundred million” differ in complexity depending if you use the simplified or traditional system. But it should be relatively easy to pick up nonetheless. But now we get to Tangut. Each character is written with considerably more strokes, and with seemingly no pattern at all. Furthermore, there is a separate set of characters for 2 to 8, which are used more often in rituals and filiation.

These characters kind of reminds me of the financial or formal numerals used in Chinese in terms of complexity, but nonetheless bear identical pronunciations for Chinese numerals. These characters are most known to appear in banknotes of Taiwan (New Taiwanese Dollar), China (Renminbi), Hong Kong (Hong Kong Dollar), and Macau (Macau Patacas).

The Tangut script still continues to garner interest in some to this day. With its digitisation and font being set up, this bizarre writing system could now be typed, and its records preserved on the digital space. Babelstone contains many Tangut resources surrounding its language, writing system, poetry and literature, and music. It contains some of the primary sources used in writing this post, and I highly recommend you checking it out. Tangut may be dead, but its interest lives on. With institutes and academics specialising in studying the Tangut language, culture, and history, perhaps we could uncover more about this language over time. Someone might just decide to start a Tangut revitalisation effort too.